The old newspaper clippings will tell you that the Harlem Riot of 1943 was sparked by a woman named Margie Polite who forgot her manners.

The old newspaper clippings will tell you that the Harlem Riot of 1943 was sparked by a woman named Margie Polite who forgot her manners.

It was Aug. 1, 1943, a Sunday night.

The details were sketchy even then, and time has added layers of gauze.

But rookie patrolman James Collins was posted at the Braddock Hotel, 126th St. and Eighth Ave., on a ‘hot-sheets’ assignment.

Twenty soldiers and sailors were said to have been infected with venereal disease during romps at the Braddock. The military asked police for help since it was wartime and America needed to keep its enlistees able-bodied, head to toe.

So the young cop’s job was to shoo GIs away from the Braddock’s sexual bed bugs.

At about 7 p.m., Collins was drawn into the ruckus when Polite, a hotel guest dissatisfied with her accommodations, got “loud and boisterous.”

As Collins arrested Polite, Army Pvt. Robert Bandy, on leave from his post in Jersey City, stepped in.

Bandy and the cop tussled over his nightstick. As the soldier broke away, Collins fired a gunshot that nicked him in the back, at his shoulder.

Bandy was taken to the nearby Syndenham Hospital with a minor wound.

But that’s not the story that went around.

“Wild rumors spread quickly through Harlem,” the Daily News’ Neal Patterson wrote. “About 3,000 Negroes gathered around the Syndenham, many of them screaming and yelling. . . . Trouble-makers cried that a cop had ‘murdered’ a Negro soldier.”

Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia rushed to the W. 123rd St. police stationhouse, where a second throng had gathered. He begged them to go home. Most wouldn’t budge.

After sunset, with Harlem darkened by a wartime dim-out, churning groups of riled citizens stalked along W. 125th St. The first of 4,500 plate-glass store windows was smashed at 10:30 p.m.

Over the next eight hours, Harlem became an apocalyptic place.

Some 1,500 businesses were invaded by looters who poached alcohol, clothing, food, furniture and furs.

Overwhelmed and outnumbered, cops coursed through the streets in patrol cars, firing warnings shots — for the most part.

Patterson wrote, “Here and there, bullets — of police or rioters — dropped men in the street, to die or to lie groaning, until hard-pressed ambulances could pick them up.”

Police shot and killed at least five men overnight, including alleged looters at a W. 136th St. grocery store, a West 125th Street luggage shop and an Eighth Ave. pawn emporium. Explanations were wooly. For example, police said officers fired “several shots” while ejecting looters at the pawnshop.

About 500 citizens and 40 cops were hurt, many of them struck with bricks, bottles and garbage cans that rained down from windows and rooftops.

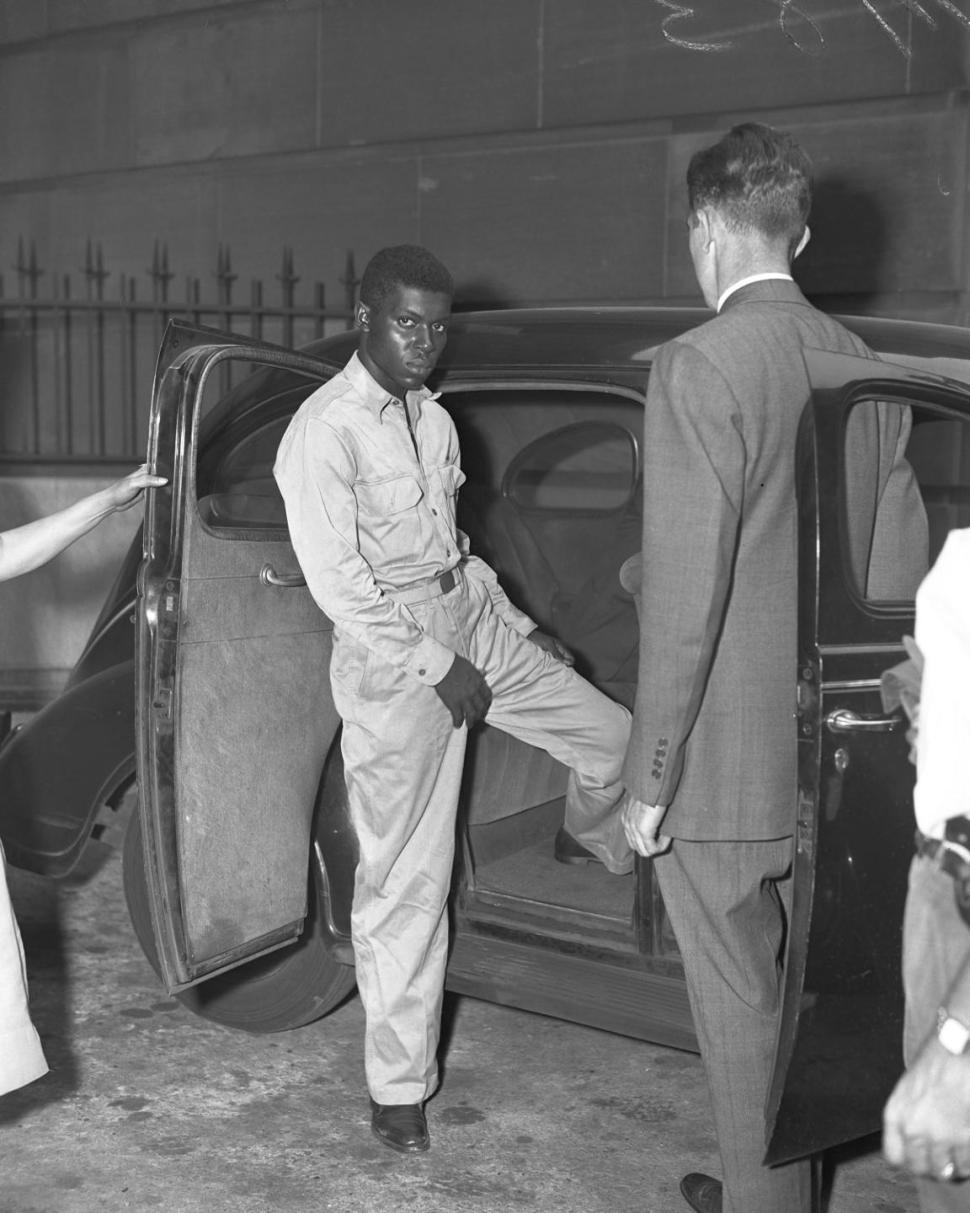

Police collared 500 people, and they perp-walked an array of zoot-suited accused looters, many of them toting stolen goods as props. One young man faced the Speed Graphics with a case of pinched gin on his shoulder. Another wore a top hat and tux made for a man twice his size.

LaGuardia imposed a 10:30 p.m. curfew. Alcohol sales were banned in Harlem, which was closed to traffic river to river. The area was flooded with 16,000 peacekeepers, including troops, cops, and air raid wardens.

Uptown was on tenterhooks for several days, but there was no further violence. Bandy recovered, and Polite was sentenced to a year of probation.

Explanations then commenced.

LaGuardia said the rioting had been “instigated and artificially stimulated” by “radicals.”

Magistrate Thomas Aurelia, who arraigned many rioters, puzzled over the loss of Harlem’s “peace and harmony.”

“Now of late, on the slightest provocation, large numbers are moved to disorder as if giving expression to some pent-up feelings,” Aurelia said. “It seems to me that some insidious propaganda is misleading otherwise peaceful people.”

But the Harlem violence had followed race riots that summer in Detroit and Beaumont, Tex., and it hearkened to a 1935 uprising on the same uptown streets.

For many black New Yorkers, the motivations seemed obvious.

Asked to serve as soldiers abroad, blacks had second-class status at home, working lousy jobs and living in dingy tenements with police as an occupying force.

Adam Clayton Powell Sr., the Harlem pastor and activist, blamed “a callous white power structure.”

“When Bandy hit Collins over the head with that club, he was not mad with him only for arresting a colored woman, but he was mad with every white policeman throughout the United States who had constantly beaten, wounded and often killed colored men and women without provocation,” Powell wrote in his book “Riots and Ruins.”

Langston Hughes added his slant in the poem “The Ballad of Margie Polite.”

It began, “If Margie Polite/Had of been white

She might not’ve cussed/Out the cop that night.”

Mariame Kaba, a New York-born writer and activist who has researched riots, says a narrative arc connects the 1943 upheaval in Harlem with recent rioting in Baltimore.

“What’s the same is all of the underlying conditions that reinforce inequality and make some people feel captive within their particular communities,” Kaba told the Justice Story. “They feel that they have limited economic opportunities, their grievances are unaddressed, and they have an antagonist relationship with law enforcement.”

Today, access to social media seems to be transforming the dynamic for those who feel oppressed, Kaba said: “It amplifies their screams.”

Via NY Daily News

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact