This year marks the 500th anniversary of the opening of the Venetian Ghetto, where the city’s Jews were forced to live for nearly 300 years. Those for whom the term “ghetto” suggests the uprising against the Nazis in Warsaw or the riots in Harlem in 1964 may find it strange that this anniversary is being treated as a celebration. The events have included a concert in March at La Fenice opera house, a ceremonious promotional video, in which slogans like “deep cultural roots” and “a unique heritage” flash over images of Venice’s Canton Synagogue and the first-ever performance of William Shakespeare’s “The Merchant of Venice” in the ghetto.

This year marks the 500th anniversary of the opening of the Venetian Ghetto, where the city’s Jews were forced to live for nearly 300 years. Those for whom the term “ghetto” suggests the uprising against the Nazis in Warsaw or the riots in Harlem in 1964 may find it strange that this anniversary is being treated as a celebration. The events have included a concert in March at La Fenice opera house, a ceremonious promotional video, in which slogans like “deep cultural roots” and “a unique heritage” flash over images of Venice’s Canton Synagogue and the first-ever performance of William Shakespeare’s “The Merchant of Venice” in the ghetto.

Why, one might ask, is Venice commemorating the creation of a ghetto, rather than its emancipation by Napoleon, whose bicentennial in 1997 passed with far less fanfare?

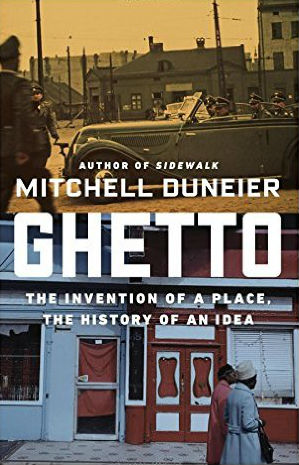

Princeton sociologist Mitchell Duneier’s marvelously rich new book, “Ghetto: The Invention of a Place, the History of an Idea,” answers this question about Venice, even as it focuses on African-American ghettos in the United States. Duneier frames his history of urban black life in America by showing how pre-modern Jewish ghettos were complex spaces in which Jews suffered but also thrived, spaces that differed wildly from both the Nazi and American spaces that inherited their names. This distinction underscores one of the book’s central points — that the “ghetto is an intergenerational phenomenon,” such that “much is lost when the larger history of ghettoization recedes.” Duneier tells that larger history through portraits of black scholars of the ghetto, each placed in the context of a historical moment and city: Chicago in 1944, for instance, or Harlem in 2004.

Princeton sociologist Mitchell Duneier’s marvelously rich new book, “Ghetto: The Invention of a Place, the History of an Idea,” answers this question about Venice, even as it focuses on African-American ghettos in the United States. Duneier frames his history of urban black life in America by showing how pre-modern Jewish ghettos were complex spaces in which Jews suffered but also thrived, spaces that differed wildly from both the Nazi and American spaces that inherited their names. This distinction underscores one of the book’s central points — that the “ghetto is an intergenerational phenomenon,” such that “much is lost when the larger history of ghettoization recedes.” Duneier tells that larger history through portraits of black scholars of the ghetto, each placed in the context of a historical moment and city: Chicago in 1944, for instance, or Harlem in 2004.

Duneier argues that “ghetto” should not be a generic term for low-income urban areas. Rather, following many of the black sociologists and activists whose stories he tells, he suggests the term, as it applies to the U.S., is best used to denote “a space for the intrusive control of poor blacks.”

“Ghetto” is never strident or even particularly argumentative. Nonetheless, its story repeatedly emphasizes the failures of the apolitical and ahistorical social science that has shaped much government and nonprofit urban policy in contemporary America. While the book celebrates social science’s triumphs, it also shows how some social scientists have relied on numbers and ignored messy racial histories, producing too-convenient quick fixes for black poverty.

Further, sociology that lumps black ghettos together with other low-income communities cannot explain long-standing, entrenched American racism and the specific impact it has had on urban black life. Duneier’s detailed story of ideas, cities, policies and individual scholars offers a politically and historically thick alternative to the type of pseudo-objective, politically blind social science popular with Michael Bloomberg, Bill Gates, Arne Duncan and other American policy-making elites.

Pre-modern vs. Nazi ghettos

Understanding the black ghetto starts with the Jews. Duneier argues that we mistakenly think of pre-modern ghettos (like Venice’s) as similar to Nazi ghettos. In part, that reflects Nazi propaganda. Hitler “framed his ghetto as a long-established standard operating procedure” in the hopes that feigning continuity with the past would blunt international criticism. In fact, by restricting where people could live by race rather than religion, Nazi ghettos radically departed from medieval and early modern Jewish enclaves. Jews living in Nazi ghettos could not convert out, as they could in pre-modern Europe. The Nazis attempted to eliminate commerce between gentiles and Jews, whereas early modern ghettos existed in large part to facilitate Jewish involvement in gentile economies while controlling the perceived religious threat of Judaism. Nazi ghettos, sites of regular shootings, beatings and murders, were part of an extermination process. This violence differed categorically from the sporadic pogroms of pre-modern anti-Semitism.

Nazi officers talking with Jews in the Warsaw ghetto in Poland in 1943. An AP investigation found dozens of suspected Nazi war criminals collected millions of dollars in Social Security payments.AP

Ironically, the idea that Nazi ghettos were “traditional” survived among respectable post-war historians (and many Jews!). Modern post-Enlightenment historians often found it convenient to conflate pre-modern and Nazi ghettos, because it confirmed their harsh judgments of pre-modern Christianity. Of course, understanding Venice’s 500th anniversary celebration requires unlearning this history and disentangling pre-modern from Nazi ghettos. To be sure, Venice’s Jews faced onerous taxes and sporadic violence, but the ghetto also hosted a mixture of Spanish, German, Italian and Levantine Jews (along with a synagogue for each community), supported a long-standing Jewish culture — and made some Jews very rich.

Understanding why black scholars in the U.S. adopted the term “ghetto” to describe their own communities also requires such disentangling. Duneier shows how using “ghetto” to talk about black neighborhoods took hold in the early 1940s, for two reasons. First, few African Americans visited Europe until World War II, when many drafted black men traveled to France, Germany and Italy, where they often compared American racism to the experiences of European minorities. Second, and more pointedly, Duneier shows how black scholars in the ’40s invoked “ghetto” specifically in response to “the rise in attention to the Nazi treatment of Jews in Europe.” Black writers mined the analogy between the two ghettos, and particularly the horror of Nazi misdeeds in Warsaw, to wake American whites from their racial apathy.

Further, black scholars invoked ghettos to differentiate their own neighborhoods from those of poor, whiter immigrants. In one chapter, Duneier focuses on Horace Cayton, who studied sociology at the University of Chicago where he helped oversee a massive research project into black life in Chicago’s South Side. Cayton and his collaborator St. Clair Drake’s 1945 sociological masterpiece, “Black Metropolis,” which drew on that archive, actually repudiates the influential Chicago school of sociology, which thought that neighborhoods emerged from “natural forces,” independent of social policy. That school interpreted black enclaves as basically similar to poor “zones in transition,” through which poor European immigrants to Chicago passed before they became middle class. These zones formed organically and fostered crime and disease, but residency in them was strictly temporary. For the Chicago school, race was incidental.

By contrast, “Black Metropolis” used the term “ghetto” because Cayton and Drake emphasized the role of white racism: Blacks were poor because they were denied access to good jobs and they lived in crowded ghettos because of housing discrimination. Often this took the form of “restrictive covenants”: private deals made within white residential areas not to sell to blacks. “Black Metropolis” thus used intensive, fine-grained sociological work to show how black ghettos differed from other poor Chicago neighborhoods.

Unfortunately, Cayton and Drake’s work was largely ignored by post-war white America. A year before they published it, the Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal, funded by the Carnegie Corporation, released “An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy,” a best seller that dominated public discussion around race in the U.S. Myrdal understood white prejudice as a response to the unsavory conditions of black poverty, and he overlooked the force of covenants and other forms of discrimination in the north. Sadly, his blockbuster over-shadowed “Black Metropolis.”

Haunting melancholy

Cayton in 1944 Chicago is just one of Duneier’s stories, each researched in great detail and told in a flowing narrative and clear prose. (About the only thing missing is an introduction; Duneier is so committed to historical narrative that it requires serious thought to infer his major arguments.) Alongside Cayton, Duneier has chapters about Kenneth and Mami Clark, who pioneered psychological work on racial prejudice in mid-century Harlem, which was cited when the Supreme Court desegregated schools in Brown v. Board of Education; William Julius Wilson, whose controversial theory of how the black middle class fled historically black neighborhoods in cities like New York and Chicago and produced a newly depressed ghetto was frequently misunderstood (including by Ronald Reagan, who tried to hire Wilson, much to the latter’s chagrin); and Geoffrey Canada, the social entrepreneur responsible for the Harlem Children’s Zone, an immersive attempt to help children escape the cycle of poverty. Numerous other figures crowd the pages of Duneier’s “Ghetto.”

While the book celebrates brilliant urban scholarship, particularly by black thinkers, the melancholy that haunts Cayton’s story persists to the present. Myrdal’s faith in the “American Creed” of “liberty, equality, justice, and fair opportunity for everybody” has always been more popular than examination of racist laws and institutions. You can hear Myrdal’s heirs today insisting, in response to Black Lives Matter protests against police violence, that “All Lives Matter.” With this slogan, whites refuse to confront the specificity of deep-seated American racism.

Further, the optimistic view that quantitative social science will help fix deep, historically rooted problems undergirds the education reform movement, probably the best-known urban policy initiative in America. (To be clear, Duneier has no aversion to quantitative methods; the problem is when social scientists both ignore race and imagine they can isolate the single variable that will lift blacks out of poverty.) Duneier’s chapter on Canada is particularly good in exposing the dangers of extensive donor involvement in public schools, the folly of utopian education experiments that attempt to find the variable that will save students from the ghetto, and the unrealistic expectations that such high-stakes social science places on teachers and school administrators.

Finally, Duneier traces how white scholars and policy makers privilege “race-blind” solutions. These ideas ignore the structuring force of racism. Especially since the Reagan Revolution of the 1980s, they also assume the impossibility of asking “the white masses to make sacrifices on behalf of blacks.” The parts of “Ghetto” that focus on white incapacity to grapple with racism and its history make for very sad reading. Nearly a century has passed since the Great Migration began, bringing tens of thousands of blacks to northern cities.

Venetians may be celebrating, but Duneier’s book suggests that white Americans should instead use their own ghettos’ centennial to ask some hard questions about race and imagine how the next 100 years might be different.

“Ghetto: The Invention of a Place, the History of an Idea,” by Mitchell Duneier, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 292 pp., $28. Source

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact