The Battle of Harlem Heights was fought during the New York and New Jersey campaign of the American Revolutionary War.

The Battle of Harlem Heights was fought during the New York and New Jersey campaign of the American Revolutionary War.

The action took place in what is now the Morningside Heights and east into the future Harlem neighborhoods of northwestern Manhattan Island in New York Town on September 16, 1776.

The Continental Army, under Commander-in-Chief General George Washington, Major General Nathanael Greene, and Major General Israel Putnam, totaling around 1,800 men, held a series of high-ground positions in upper Manhattan against an attacking British Army division totaling around 5,000 men under the command of Major General Alexander Leslie.

British troops made a tactical error by having their light infantry buglers sound a fox hunting call, “gone away,” while in pursuit.

This was intended to insult Washington, himself a keen fox hunter, who learned the sport from his neighbor and mentor near Alexandria, Virginia, the Sixth Lord Fairfax (Thomas Fairfax) during the French and Indian War.

“Gone away” means that a fox is in full flight from the hounds on its trail. The Continentals, who were in an orderly retreat, were infuriated by this and galvanized to hold their ground .

After flanking the British attackers, the Americans slowly pushed the British back. After the British withdrawal, Washington had his troops end the pursuit. The battle went a long way to restoring the confidence of the Continental Army after suffering several defeats. It was Washington’s first battlefield victory of the war.

After a month without any major fighting between the armies, Washington was forced to withdraw his army north to the town of White Plains in southeastern New York when the British moved north into Westchester County and threatened to trap Washington further south on Manhattan. Washington suffered two more defeats, at White Plains and Fort Washington.

After these two defeats, and also with the evacuation of Fort Lee (named after his deputy, General Charles Lee) across the Hudson River guarding the western shore in New Jersey, Washington and the army retreated across New Jersey to Pennsylvania. The New York and New Jersey campaign ended after the subsequent American Christmas victories at Trenton and Princeton, which reinvigorated the Continental Army and the new nation.

On August 27, 1776, British troops under the command of General William Howe flanked and defeated the American army at the Battle of Long Island. Howe moved his forces and pinned the Americans down at Brooklyn Heights, with the East River to the American rear. On the night of August 29, General George Washington

, Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, evacuated his entire army of 9,000 men and their equipment across the water to Manhattan.

On September 15, Howe landed his army in an amphibious operation at Kip’s Bay, on the eastern shore of Manhattan, along the East River. After a bombardment of the American positions on the shore, 4,000 British and Hessian troops landed at Battle of Kip’s Bay. The American troops began to flee at the sight of the enemy, and even with Washington’s arrival on the scene and taking immediate bold command, demanding his soldiers to fight, they refused to obey orders and continued to flee.

After scattering the Americans at Kip’s Bay, Howe landed 9,000 more troops, but mysteriously did not immediately cut off the American retreat from New York Town in the south of the island. Washington had all of his troops in the city on their way to north along the westside of Manhattan to Harlem Heights by 4:00 pm and they all reached the fortifications on the Heights by nightfall.

On the morning of September 16, Washington received word that the British were advancing. Washington, who had been expecting an attack, sent a reconnoitering party of 150 men under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Knowlton to probe the British lines. At daybreak, Knowlton’s troops were spotted by the pickets of the British light infantry. The British sent two or three companies to attack the enemy.

For more than half an hour the skirmish continued, with fighting in the woods between two farm fields. When Knowlton realized that the numerically superior British forces were trying to turn his flank, he ordered a retreat. The retreat was organized and conducted with no confusion or loss of life.

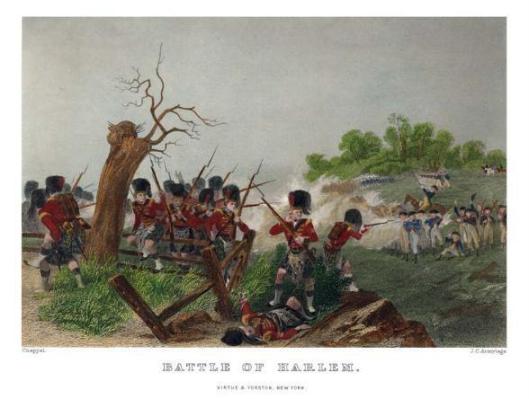

The British quickly pursued the Americans and were reinforced with the Second and Third battalions of light infantry, along with the 42nd Highlanders. During the retreat, the British light troops played their bugle horns signaling a fox hunt, which infuriated the Americans. Colonel Joseph Reed, who had accompanied Knowlton, rode to Washington to tell him what was going on and encouraged him to reinforce the rangers.

Instead of retreating, Washington, in what Edward G. Lengel calls “an early glimmer of the courage and resolve that would rally the Continentals from many a tight spot later on”, devised a plan to entrap the British light troops.

Washington would have some troops make a feint, in order to draw the British into a hollow way, and then send a detachment of troops around to trap the British inside.

The feint party was composed of 150 volunteers who ran into the hollow way and began to engage the British. After the British were in the hollow way, the 150 volunteers were reinforced by 900 more men. All of the troops were stationed too far away from one another to do much damage.

The flanking party consisted of Knowlton’s Rangers, which had been reinforced by three companies of riflemen, in total about 200 men. As they approached, an officer accidentally misled the men, and the firing broke out on the British flank, not their rear. The British troops, realizing that they had almost been surrounded, retreated to a field, where there was a fence.

The Americans soon pursued and, during the attack, Knowlton was killed. Despite this, the American troops pushed on; driving the British troops beyond the fence to the top of a hill. When they reached the hill, the British forces received reinforcements; including some artillery. For two hours, the British troops held their ground at the top of the hill until the Americans once again forced them to retreat, into a buckwheat field.

Washington was originally reluctant to pursue the British troops, but after seeing that his men were slowly pushing the British back, he sent in reinforcements and permitted the troops to engage in a direct attack. By the time that all of the reinforcements arrived, nearly 1,800 Americans were engaged in the buckwheat field. To direct the battle, members of Washington’s staff, including Nathanael Greene, were sent in. By this time, the British troops had also been reinforced; bringing their strength up to about 5,000 men.

For an hour-and-a-half, the battle continued in the field and in the surrounding hills until, “having fired away their ammunition”, the British withdrew. The Americans kept up a close pursuit until it was heard that British reserves were coming, and Washington, fearing a British trap, ordered a withdrawal. Upon hearing Washington’s orders to withdraw, the troops gave a loud “huzzah” and left the field in good order.

The British casualties were officially reported by Howe at 14 killed and 78 wounded. However, a member of Howe’s staff wrote in his diary that the loss was 14 killed and 154 wounded. David McCullough gives much higher figures of 90 killed and 300 wounded.

The Americans had about 30 killed and 100 wounded, including among the dead, Knowlton and Major Andrew Leitch. The American victory raised morale in the ranks, even among those who had not been engaged. It also marked the first victory of the war for the army directly under George Washington’s command.

There was little fighting for the next month of the campaign, but Washington moved his army to White Plains in October after hearing that the British were attempting to trap him on Manhattan. After being defeated at the Battle of White Plains and later at Fort Washington, Washington and his army retreated across New Jersey, pursued by the British, into Pennsylvania.

The loss of Knowlton was a blow to the fledgling American intelligence operations, as he had created and led the first such unit of the Continental Army, at the direction of Washington (source).

- Governor Hochul Bolsters Subway Security With National Guard Deployment

- Book Launch; ‘Beyond Architecture: The NEW New York’ By Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel

- Sponsored Love: Daddy’s Greek Potato Pie, A Book About Healthy Eating By CC Minton

- The Wider Applications Of AI Image Generators In Everyday Lives

- HubSpot Marketing Hub Implementation | Complete Guide

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact