Luisa Moreno , August 30, 1907 – November 4, 1992, was a leader in the United States labor movement and a social activist.

She unionized workers, led strikes, wrote pamphlets in English and Spanish, and convened the 1939 Congreso de Pueblos de Habla Española, the “first national Latino civil rights assembly”, before returning to Guatemala in 1950.

Moreno was born Blanca Rosa López Rodríguez to a wealthy family in Guatemala City, Guatemala. Disenchanted with the gender restrictions on educational attainment, she organized her elite, wealthy peers into La Sociedad Gabriela Mistral.

This group used petition drives and informal lobbying to successfully advocate for the admission of women to Guatemalan universities. Rejecting her elite status, she went to Mexico City at the age of nineteen to pursue a career in journalism.

While there, she also wrote poetry. She married Angel De León, an artist, in 1927 and together they moved to New York City the following year. There, her daughter Mytyl was born.

Early life

While in New York, the Warner Bros. movie Under a Texas Moon (1930) was protested as anti-Mexican by a group of Latinos led by Gonzalo González. Police brutalized the picketers, killing González.

The murder sparked a Pan-Latino protest, in which Moreno participated. She later told Bert Corona that the experience “motivated her to work on behalf of unifying the Spanish-speaking communities.”

She was a graduate of the Catholic women’s university College of the Holy Names in Oakland, California.

Union and civil rights activism

The Great Depression struck in 1929, and in order to support her daughter and unemployed husband, Moreno worked as a seamstress in Spanish Harlem. She organized her co-workers, most of whom were Latinas, into a garment workers union.

In 1935, Moreno was hired by the American Federation of Labor (AFL) as a professional organizer. She left her husband, who had become physically abusive, and settled with her daughter in Florida, where she unionized African-American and Latina cigar-rollers. She joined the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) and became a representative of the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing, and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA), becoming the editor of its Spanish-language newspaper in 1940.

As UCAPAWA representative, she helped organize workers at pecan-shelling plants in San Antonio, Texas, and cannery workers in Los Angeles. There, she encouraged alliances between workers at different plants. Her leadership was of the type that empowered other workers, especially women, and she strongly encouraged women to take leadership roles in union organizations.

In 1937, she settled the Encanto neighborhood of San Diego, which she used as a base for her nationwide activism.

In 1939 she was one of the main organizers, alongside Josefina Fierro de Bright and Eduardo Quevedo, of the El Congreso de Pueblos de Habla Española (Spanish-speaking People’s Congress). She took a year off from UCAPAWA to travel throughout the U.S., visiting Latino workers on the East Coast, in the Southwest, and allying refugees of the Spanish Civil War to her cause.

In 1940, she was asked to speak before the American Committee for the Protection of the Foreign Born (ACPFB). Her speech, which became known as the “Caravan of Sorrow” speech, eloquently described the lives of migrant Mexican workers. Portions of it were reprinted in Committee pamphlets, creating a legacy that lasted much longer than the duration of the speech itself. In it, she stated,

These people are not aliens. They have contributed their endurance, sacrifices, youth and labor to the Southwest. Indirectly, they have paid more taxes than all the stockholders of California’s industrialized agriculture, the sugar companies and the large cotton interests, that operate or have operated with the labor of Mexican workers.

In the same year, she co-founded an employment office in San Diego with her friend Robert Galván. She also organized San Diego-area cannery workers and persuaded employers not to hire scab workers. With the dawn of World War II, the defense industry became a major employer in the United States, particularly in San Diego. Mexicans, however, were forbidden to work in the petroleum industry, shipyards, and other war-related fields, and were relegated to the lowest-paying jobs. Moreno criticized the discrimination, pointing out that “California has become prosperous with the toil and sweat of Mexican immigration attending to its number one industry, agriculture. Now they have sustained a true and lasting patriotism to a democratic country that refuses to give them citizenship or even basic civil rights.”

In 1942, Moreno became involved in the Sleepy Lagoon murder trial, a cause célèbre for the American left and Mexican-American civil rights activists. Along with longtime friend Bert Corona and attorney Carey McWilliams, she organized the Sleepy Lagoon Defense Committee to exonerate the indicted youths. In addition to mounting a legal defense, the Committee sought to put to rest rumors about “violent gangs” of Pachucos and to counter sensationalist reports of urban “guerrilla warfare” between Pachucos and servicemen. (The press had dubbed the 1943 attacks of Pachucos the “Zoot Suit Riots”.) She also investigated abuses on the part of servicemen in San Diego, advising city councilperson Charles C. Dail on the matter. She invited Admiral David W. Bagley, commandant of the Eleventh Naval District in San Diego, to a meeting of San Diego-area community and labor leaders. Bagley did not respond to the invitation. Continuing to press for an investigation, Moreno collaborated with McWilliams to gather evidence. The investigation outraged California State Senator Jack B. Tenney, who lashed out at Moreno, publicly accusing her of engaging in an “anti-American conspiracy.”

During her Zoot Suit campaigns, she continued to work in the labor movement. In the city of El Monte, she represented walnut pickers, receiving the assistance of the California Walnut Growers Association. One Association representative “came to have a high regard for her character, ability and honesty.”

In 1947, she married Gray Bemis, a navy veteran from Nebraska who had been a delegate to the 1932 Socialist Party of America national convention. Bemis shared Moreno’s interest in the civil rights of Mexican Americans, and photographed many of her activities.

In the late 1940s, Moreno established a San Diego chapter of the Mexican Civil Rights Committee. In speeches to chapters of the Young Progressives of America, she warned that racial tensions and communist hysteria provoked racial profiling, stereotyping and police brutality against Mexican Americans and other ethnic minorities.

Deportation

During the 1950s, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) conducted Operation Wetback to forcibly deport Mexicans and Mexican Americans. The operation targeted labor leaders in particular. While she was considered polite and law abiding, her activism earned her enemies. She and her husband began receiving threatening letters for their work against police brutality.

Tenney, who labeled her a “dangerous alien”, was instrumental in her deportation. She was offered citizenship in exchange for testifying against Harry Bridges, but refused to be “a free woman with a mortgaged soul.”

On November 30, 1950, Moreno and her second husband, Gary Bemis of Nebraska, left the United States via Ciudad Juárez, slowly making their way to Mexico City. Her warrant of deportation had been issued on the grounds that she had once been a member of the Communist Party.

Eventually, the couple settled in Guatemala, but were forced to flee when a 1954 CIA-sponsored coup ousted progressive President Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán.

After the triumph of the 1959 Cuban Revolution, Moreno spent time teaching on the island. She later returned to Guatemala, where she was interviewed by several historians before she died.

Legacy

Although Luisa Moreno is a major figure in the pre-Chicano Movement and the American labor movement, her role is often overlooked.

Since the 1970s, activists and historians have attempted to reconstruct her role in the movements and give her appropriate credit. Among them are the muralist and professor Judy Baca, who memorialized the organization of Cal San workers in her Great Wall of Los Angeles.

The wall, a visual representation of the history of Los Angeles, pays tribute to Moreno by including an image of her face surrounded by images of strikers. Moreno’s story has been featured in the National Museum of American History’s “American Enterprise” installation.

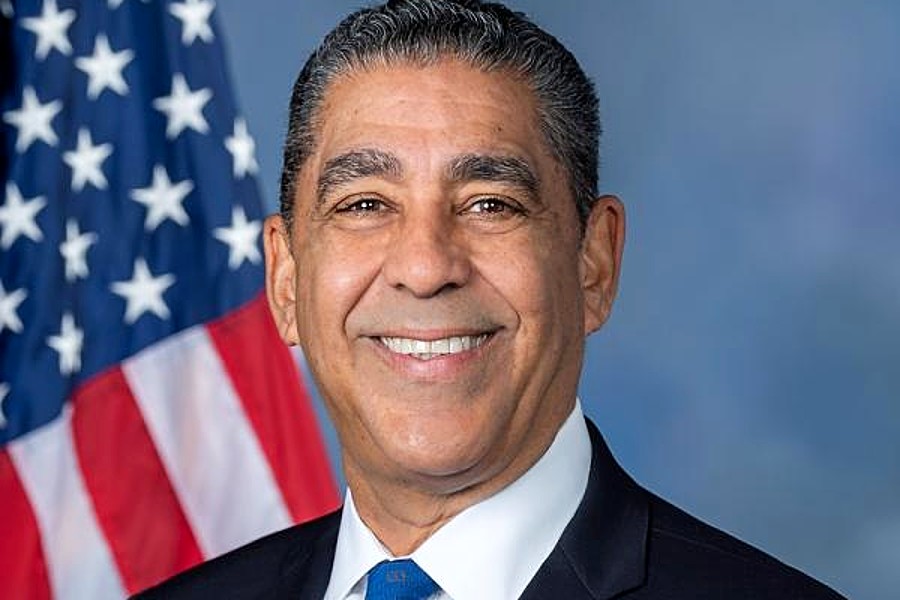

Luisa Moreno stands on a balcony in Mexico City, 1927. Photograph used on promotional postcard for “Latinas in the United States: A Historical Encyclopedia.” Gift of Vicki L. Ruiz.

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact