A dynamic librarian who established a research library.

A brilliant behind-the-scenes organizer who harnessed the energy and enthusiasm of young people into vital participants in the civil rights movement—plus, she assisted some of the movement’s most famous men. A visionary sculptor who educated a generation of groundbreaking artists.

These are some of the history-making and magnificent women in the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture’s collections.

The 31 days of March, Women’s History Month, are a terrific time to explore the Center’s materials to learn more about fearless women who left powerful legacies and changed the world.

Ella Baker

Ella Baker (1903-1986), who preferred to work behind the scenes, had an exceptional gift for inspiring people to take an active role in their liberation. Those skills propelled her into leadership roles and made her a go-to person for organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the New York Urban League, and the Southern Christian Leadership Council (SCLC). Activists such as A. Philip Randolph and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. sought her input.

Baker also inspired and encouraged the creation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), an organization made up of college-age students who participated in the civil rights movement. They first formed in 1960 following a Youth Leadership Meeting she co-organized at Shaw University in North Carolina. SNCC led sit-ins at lunch counters across the South advocating for desegregation, participated in the Freedom Rides of 1961, and joined voter registration efforts.

Baker had a significant connection to Harlem and the Center. She taught adult education classes and developed consumer education and literacy programs for young mothers in 1934 at the 135th Street branch of The New York Public Library. Today, the building is part of the Schomburg Center complex.

Ella Baker’s legacy? Members of SNCC included Stokely Carmichael (1941-1998)—later known as Kwame Ture—, future U.S. Congressman John Lewis (1940-2020), and future NAACP Chairman Julian Bond (1940-2015).

Additionally, Baker inspired a future president. Joseph Biden’s 2020 acceptance speech as the Democratic Party’s nominee for President of the United States quoted her. “Give people light,” he said, repeating her famous words. “They will find a way.”

Jean Blackwell Hutson

Before 1972, the Schomburg Center was part of The New York Public Library’s branch at 135th Street in Harlem and was known as the Division of Negro History, Literature and Prints. Curator and librarian Jean Blackwell Hutson (1914-1998) led the Division starting in 1948.

Her work included processing materials such as National Negro Congress and the Negro Writers Project. Hutson promoted the collections to local groups letting them know about the Library’s content. Hutson’s friends included writers and activists such as Langston Hughes, whose poems and plays would become part of the Center’s collection many years later.

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s brought renewed interest in artworks, literature, audio materials, and written histories created by and about Black people. The branch’s understaffing and high usage of its materials left the library with many of its objects damaged. There was also a backlog of items that remained unprocessed.

“Many of its aged and irreplaceable documents and memorabilia are in an advanced state of deterioration because the library has no air-conditioner to protect them against New York’s acid air,” stated a 1967 article in Ebony magazine, which called the materials “a scholar’s gold mine.” The building was also not fireproofed.

To preserve the collections, quickly process new items, increase staff, and expand storage space, Hutson championed the branch becoming a research library—where materials could not be checked out—and housed in its own building.

Hutson lobbied NYPL’s leadership to change the division’s status, took part in lobbying efforts to the New York State Legislature for funding to construct a new building at 515 Malcolm X Boulevard (then known as Lenox Avenue), gained the Harlem community’s support, and helped to establish the Schomburg Center Corporation to raise additional money.

She also served as a member of the New York State Committee for the Selection of a Permanent Site for the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Hutson’s collection in MARB has a copy of the report.

A new five-story building opened in 1980. It included five divisions of research and spaces to hold exhibitions.

Jean Blackwell Hutson’s legacy? “She is the reason we are the Schomburg Center,” said current Schomburg Center Director Joy L. Bivins. “Her footprints are all over this institution. This does not exist without her.”

Hutson served as the Center’s Chief Librarian when the Schomburg Collection transferred from The Branch Libraries to The Research Libraries effective on May 1, 1972. MARB has a copy of the memorandums in its archives.

Hutson spoke about her life as part of the Oral History Project (ID #269396) and sat with journalist Gil Noble for a conversation on his television program Like It Is. Huston also excelled at capturing history. She interviewed Black history legends such as composer Leonard de Paur (1914-1998), character actress Rosetta LeNoire (1911-2002), painter Bruce Nugent (1906-1987), and many more as part of the Center’s Oral History Project in the 1980s. MIRS holds all of these conversations.

Augusta Savage

Sculptor and activist Augusta Savage (1892-1962) is perhaps best known for the 16-foot plaster sculpture The Harp. The poem and later song, Lift Every Voice and Sing, by James Weldon Johnson and his brother John Rosamond Johnson inspired it. Organizers of the 1939’s World’s Fair asked for her design to symbolize the musical contributions of African Americans.

The decade of the 1930s brought great success to Savage. She managed an art program at NYPL’s 135th Street Branch and was later appointed as the first director of the Harlem Community Art Center. Her leadership and management of the program caught the attention of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who used it as the model for the Federal Arts Project, which President Franklin D. Roosevelt created as part of the New Deal. In 1939, Savage opened the first Black-owned art gallery.

Related: Read more Women’s History Month stories here at Harlem World Magazine.

Augusta Savage’s legacy? Her art students included painter Jacob Lawrence (“The Migration Series”) and sculptor Selma Burke (FDR’s portrait on the dime). Her gallery represented painters such as Beauford Delaney (“Can Fire in the Park”) and Lois Mailou Jones (“Les Fetiches”). All went on to create groundbreaking works, which cemented their names as some of the nation’s most critically acclaimed artists.

“I have created nothing really beautiful, really lasting, but if I can inspire one of these youngsters to develop the talent I know they possess, then my monument will be their work,” said Savage in a 1935 interview with T.R. Poston for Metropolitan Magazine.

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, 515 Malcolm X Blvd, New York, NY 10037, 212.491.2265, https://www.nypl.org/locations/schomburg

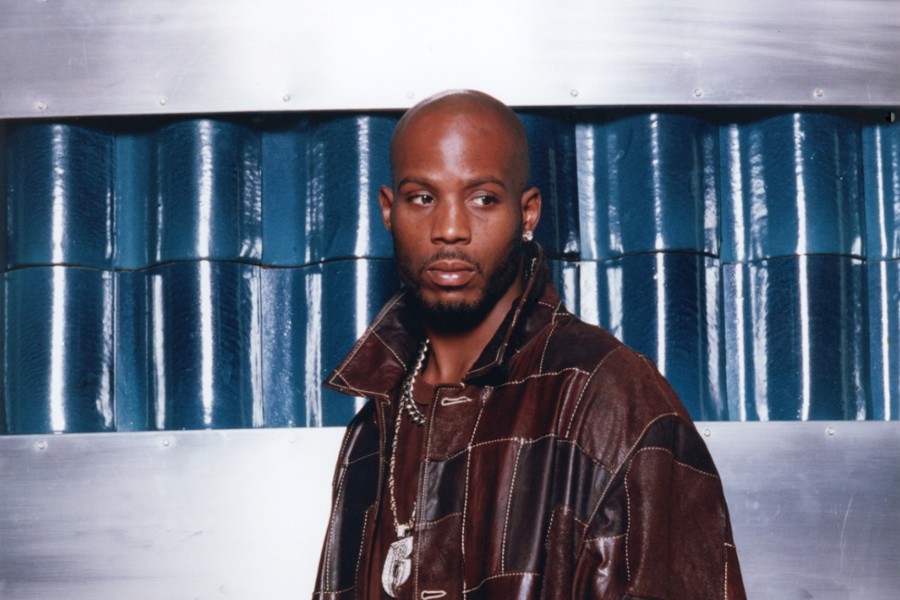

Photo credit: Left to right: Ella Baker, Jean Blackwell Hutson, and Augusta Savage. Photo of Jean Blackwell Hutson: Tucker Childs Acres Barnes Road, Vineyard Haven, Massachusetts. Photo of Augusta Savage, Digital Collections Image 4015352.

- LISC CEO Michael T. Pugh Recognized Among 2024 Worthy 100 Leaders

- NY Lawmakers Celebrate Historic MENA Data Recognition Bill Signed By Hochul

- Sponsored Love: Leadership Skills Training Courses: Invest In Your Future Today

- Senator Hoylman-Sigal Calls On Independent Schools To Adopt NYC Public School Calendar

- Mayor Adams Celebrates 65 Million NYC Visitors In 2024, Second-Highest Ever

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact