The Battle of Harlem Heights

The Battle of Harlem Heights was fought during the New York and New Jersey campaign of the American Revolutionary War

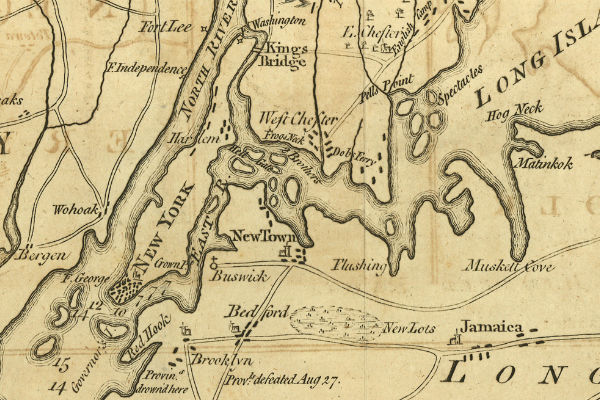

. The action took place on September 16, 1776, in what is now the Morningside Heights

area and east into the future Harlem neighborhoods of northwestern Manhattan Island in what is now part of New York City.

The Continental Army, under Commander-in-chief General George Washington, Major General Nathanael Greene, and Major General Israel Putnam, totaling around 9,000 men, held a series of high ground positions in upper Manhattan. Immediately opposite was the vanguard of the British Army totaling around 5,000 men under the command of Major General Henry Clinton.

An early morning skirmish between a patrol of Knowlton’s Rangers and British light infantry pickets developed into a running fight as the British pursued the Americans back through woods towards Washington’s position on Harlem Heights. The overconfident British light troops, having advanced too far from their lines without support, had exposed themselves to counter-attack. Washington, seeing this, ordered a flanking maneuver which failed to cut off the British force but in the face of this attack and pressure from troops arriving from the Harlem Heights position, the outnumbered British retreated. Meeting reinforcements coming from the south and with the added support of a pair of field pieces, the British light infantry turned and made a stand in open fields on Morningside Heights.

The text about the image comes from the 278-page book :

It was Nixons brigade, Greenes old command, — the same that fought sowell on Morningside Heights, — which, at a criticalpoint in the action, advanced upon the enemy at Princeton, and helped to turn the day decisively inour favor. The movements were similar,—in eachcase a fearless attack upon the regulars in the openfield. The men of the time, as we must believe not onlyfrom their own animated descriptions but from thenature of the action itself, would have accorded the Battle of Harlem Heights

a prominent place amongthe events of 1776. Far from being an isolated inci-dent of the campaign, it establishes a closer relationof events. Unexpectedly rousing a despondent army, and reassuring it of its vitality and possibilities, it could have left none other than a permanent impres-sion. The typical soldier of that field fought on. He was the patriot of the Revolution. Locally we lose sight of him only on Evacuation Day, November 25, 1783, when New York was in his handsonce more.

Text appearing after Image in the book reads:

“…our earlier historical writers and biographers,such as Gordon and Marshall, give the main factsof the Battle of Harlem Heights, Mr. Benson J. Lossingwas among the first to attempt the identification of the site.When he wrote his Field-Book of the Revolution, fewdocuments referring to the topography were available,and he made the mistake of going too far south and east. He placed the action on the flats or Plains of Harlem, around McGowans Pass, near the northeastern end of Central Park; and in consequence it was long calledthe Battle of Harlem Plains. Mr. Henry W. Dawson, with General George Clintons valuable letters to guidehim, identified the true site so far as to shift it from theplains to the high ground of the present MorningsideHeights; but having no reference to Jones or Hoag-landts houses, and being misled as to the location…”

The Americans, also reinforced, came on in strength and there followed a lengthy exchange of fire. After two hours, with ammunition running short, the British force began to pull back to their lines. Washington cut short the pursuit, unwilling to risk a general engagement with the British main force, and withdrew to his own lines.

The battle helped restore the confidence of the Continental Army after suffering several defeats. It was Washington’s first battlefield success of the war.

After a month without any major fighting between the armies, Washington was forced to withdraw his army north to the town of White Plains in southeastern New York when the British moved north into Westchester County and threatened to trap Washington further south on Manhattan. After two defeats Washington retreated west across the Hudson River.

Background

On August 27, 1776, British troops under the command of General William Howe flanked and defeated the American army at the Battle of Long Island. Howe moved his forces and pinned the Americans down at Brooklyn Heights, with the East River to the American rear. On the night of August 29, General George Washington, Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, evacuated his entire army of 9,000 men and their equipment across the water to Manhattan.

On September 15, Howe landed his army in an amphibious operation at Kip’s Bay, on the eastern shore of Manhattan, along the East River. After a bombardment of the American positions on the shore, 4,000 British and Hessian troops landed at Kip’s Bay. The American troops began to flee at the sight of the enemy, and even after Washington arrived on the scene and took immediate command, demanding that his soldiers fight, they refused to obey orders and continued to flee.

After scattering the Americans at Kip’s Bay, Howe landed 9,000 more troops, but did not immediately cut off the American retreat from New York Town in the south of the island. Washington had all of his troops in the city on their way to north along the west side of Manhattan to Harlem Heights by 4:00 pm and they all reached the fortifications on the Heights by nightfall.

Battle

Early on September 16, Washington received reports, which proved to be unfounded, that the British were advancing. Washington, who had been expecting an attack, had ordered a party of 150 men under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Knowlton to reconnoiter the British lines. At daybreak, Knowlton’s troops were spotted by British pickets from Brigadier Alexander Leslie’s Light Infantry brigade. Two or three companies of the 2nd Light Infantry Battalion advanced to attack the enemy to their front. For more than half an hour the skirmish continued, in the woods spanning two farm properties, Jones’ and Hoaglandt’s. When Knowlton realized that the numerically superior British forces were about to turn his flank, he ordered a retreat, which was conducted “without confusion or loss”, although perhaps ten men had been lost in the initial skirmish.

The British followed in rapid pursuit. Knowlton’s party emerged into the open on the edge of the woods overlooking a wide re-entrant known as the Hollow Way, which marked the forward edge of Washington’s position. The rangers crossed into the American lines while the pursuing light infantry, on reaching the tree line, paused to reorganize. The sound of their bugle calls, whether calling the skirmishers to regroup or calling for reinforcements, to Colonel Joseph Reed, Washington’s Adjutant General, were reminiscent of a fox hunt, and seemed to him to be intended as an insult. Probably about this time, elements of the 2nd and 3rd Light Infantry Battalions, along with the 42nd Highlanders were ordered up as reinforcements. Reed, who had gone forward to confer with Knowlton, rode back to brief Washington and encouraged him to reinforce the rangers. Washington, seeing an opportunity to revive the spirits of his men, devised a plan to entrap the unwary enemy patrol. He ordered troops forward to make a diversionary attack, in order to draw the British down into the Hollow Way, while another detachment moved around the British right flank to cut them off.

The diversionary party, composed of 150 volunteers, ran into the Hollow Way and began to engage the British, who responded by advancing down into the valley to occupy a wooded fenceline and returned fire. The volunteers were then reinforced by a further 900 men and a prolonged exchange of fire ensued, although the two sides were too far apart to do much damage.

The flanking party consisted of Knowlton’s Rangers, reinforced by three companies of Virginia riflemen commanded by Major Andrew Leitch, in total about 200 men. As they moved forward, it seems an unidentified officer accidentally misdirected the group, and the maneuver caught the British in the flank, not their rear. During the attack, both Knowlton and Leitch were shot and fatally injured. Despite this, the American troops pushed on. The British troops, realizing that their flank was in danger, retreated uphill to occupy a fence-line. Washington reinforced his troops in the Hollow Way and together with the flanking party mounted a frontal attack. The British light infantry retired across open farmland to a buckwheat field in the area where Barnard College now stands. Here they received reinforcements; including a pair of 3-pdr guns.

Washington was originally reluctant to pursue the British troops, but after seeing that his men were slowly pushing the British back, he sent in reinforcements and permitted the troops to engage in a direct attack. By the time that all of the reinforcements arrived, nearly 1,800 Americans were engaged in the buckwheat field. To direct the battle, members of Washington’s staff, including Nathanael Greene, were sent in. By this time, the British troops had also been reinforced; bringing their strength up to a number slightly less than the attacking Americans.

For an hour-and-a-half, the battle continued in the field and in the surrounding woods until, with some units, including the 3-pdrs, having fired away their ammunition, the British began to withdraw. The Americans pressed forward in pursuit until Washington, concerned about the approach of British reserves, ordered a halt. Upon receiving Washington’s orders to return to their lines, the troops gave a loud “huzzah” and left the field in good order.

Aftermath

The British casualties were officially reported by Howe at 14 killed and 78 wounded, but a member of Howe’s staff wrote in his diary that the loss was 14 killed and 154 wounded. The author David McCullough suggests much higher figures of “probably…90 killed and about 300 wounded” but cites no source for this. Henry Johnston, whose 1897 study remains the most thorough investigation of the battle, assessed British losses at 14 killed and 157 wounded and those of the Americans at about 30 killed and 100 wounded, including Colonel Knowlton among the dead. Major Andrew Leitch, commander of the Virginia riflemen, died some days later. Both sides claimed victory. The repulse of British troops in this “pretty sharp skirmish” boosted morale in the American ranks ‘prodigiously’, as George Washington

observed, even among those who had not been engaged. It also marked the first success of the war for the army directly under Washington’s command.

There was little fighting for the next month of the campaign, but Washington moved his army to White Plains in October after hearing that the British were attempting to trap him on Manhattan. After being defeated at the Battle of White Plains

and later at Fort Washington, Washington and his army retreated across New Jersey, pursued by the British, into Pennsylvania.

The loss of Knowlton was a blow to the fledgling American intelligence operations, as he had created and led the first such unit of the Continental Army, at the direction of Washington.

Photo credit: 1) Battle of Harlem Heights, September 16, 1776, via source. 2) Harlem map via source. 3) ) Battle of Harlem Heights, September 16, 1776, via source. 5) Battle of Harlem Heights, September 16, 1776, via source.

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact