In the narrative of early photography in West Africa, there’s often a portrayal of colonization’s influence.

Europeans, armed with new technology, documented the region’s people and places, crafting a story primarily for European audiences.

But what if this narrative is only part of the story? What if there’s a more empowered and nuanced perspective that West Africa holds for itself?

These questions are central to a groundbreaking new book that reexamines the history of photography in the region.

Giulia Paoletti, an assistant professor at the University of Virginia, challenges the conventional wisdom in “Portrait and Place: Photography in Senegal, 1840-1960.”

Through extensive research and interviews in Senegal, she brings to light unpublished works and gives credit to images previously labeled anonymous.

Paoletti’s book begins by showcasing the earliest surviving photograph from West Africa, taken by Frenchman Jules Itier in 1842. But the narrative quickly shifts to highlight the Senegalese agency in photography.

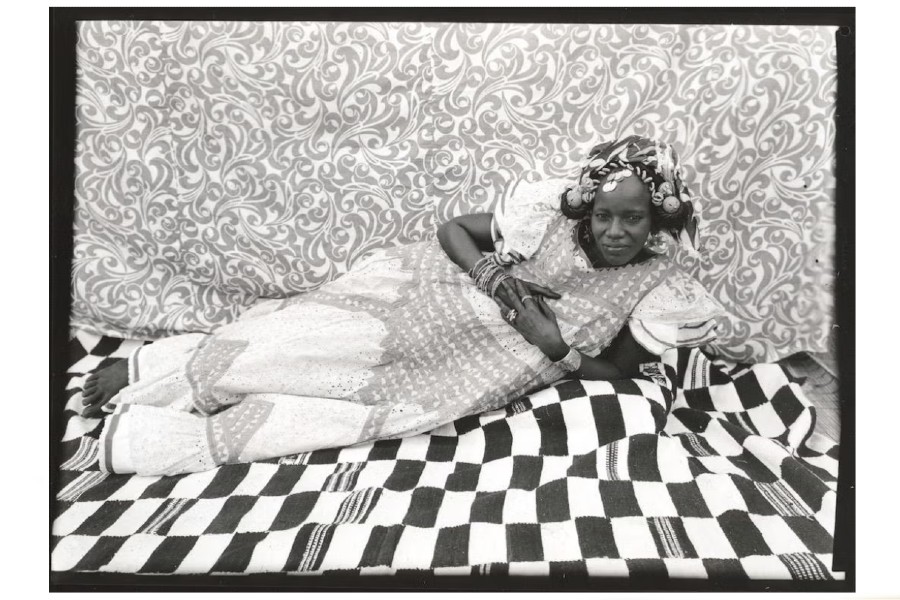

Unlike other West African nations, Senegal lacked a recorded history of portraiture before photography emerged. By the 1850s, Senegalese women were commissioning portraits in St. Louis, asserting their status and identity through photography.

The book also challenges colonial perspectives by showcasing instances where Africans asserted their modernity through photography.

For example, Belgian explorer Adolphe Burdo encountered the “King of Dakar” in 1878, who presented Burdo with a portrait commissioned by himself.

Despite this display of modernity, European accounts often marginalized or erased such expressions.

Paoletti’s research uncovers unique social functions of photography in Senegal, such as the xoymet tradition, where photographs were used to decorate a bride’s room and prompt social interactions.

Despite the prevalence of photography in Senegalese society, there remains a lack of scholarly attention to this subject.

The book highlights the interconnectedness of Senegalese photography with global trends, suggesting that it did not evolve in isolation.

Paoletti hopes to continue shedding light on Senegal’s photographic heritage, presenting her findings at various events and exhibitions.

“Portrait and Place: Photography in Senegal, 1840-1960” offers a refreshing perspective on West African photography, reclaiming narratives and identities that have been obscured by colonial lenses.

Photo credit: 1) Seydou Keïta (Malian, 1921/3–2001). 2) Senegalese Woman from around 1910 by an unknown photographer 3) Portrait And Place Book cover. Source.

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact