By Darryl Robertson

The writer of the Holy Qur’an and the Holy Bible said: “Let there be light in Harlem.” So, there was light in Harlem.

In fact, there was enough brightness in Black Manhattan to start a Renaissance and enough energy to reverberate its artsy ambiance worldwide.

Fourscore and twenty years later, a flood of soot and decay eclipsed everything delicate north of 110th street. God formed some of the world’s most complex and unique hustlers from this dirt. Although their lives proved tragic, their larger-than-life stories inspired Blacks across class lines and served Hollywood’s agenda. Hustlers like Bumpy Johnson, Frank Lucas, and Azie Faison found their lives romanticized on the big screen thanks to films like Hoodlum, The Godfather of Harlem, American Gangster, and Paid in Full, respectively.

Faison, played by Wood Harris in Paid in Full, wrote the film’s original screenplay. Roc-A-Fella Films, which oversaw the project, contracted screenwriter Thulani Davis and director Chuck Stone. Their direction of the film disappointed Faison to the point that he stayed away from the set.

“My original screenplay, Trapped, addressed key issues and transformations in my life,” Faison wrote in his memoir, Game Over. “It also explored the complexity of life as a hustler. Paid in Full fell short in these areas.”

It isn’t known what, if any, role Jay-Z played in Paid in Full but, Hov ironically rapped on “Streets is Talking.” “I seen niggas before me with a chance to write their own story/ Slip up and change the script.”

“I felt like someone took my life, commercialized it, and stripped it of all the truth, and power it formerly contained,” Faison wrote.

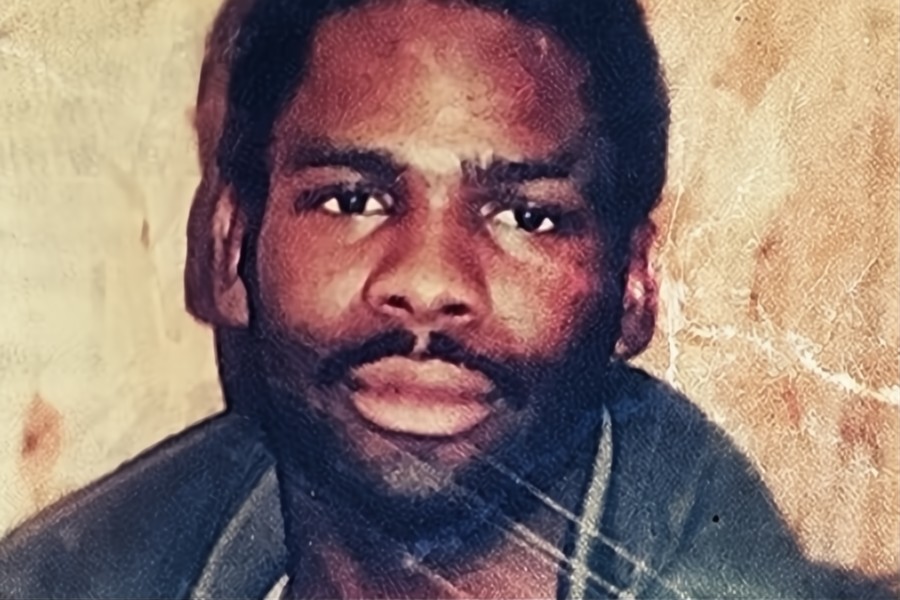

Embellishments rarely, if ever, escape Hollywood. But author Harlem Holiday isn’t with the showbiz. Nor is she into stretching the truth. Validity sits on her new book, The Harlem Plug: The Richard “Fritz” Simmons Story. “I wanted to tell Fritz’ story because the streets were talking, spreading lies,” Holiday said during interview. “I wanted to write from the perspective of his family and close friends.”

“Fritz’ spirit juxtaposes mythical aura, but he’s no myth.”

Fritz’ spirit juxtaposes mythical aura, but he’s no myth. He really choked the streets by moving 300–500 kilos a month. The hushed hustler from 112th street supplied some of NYC’s biggest drug dealers, including Rich Porter. But, outside of a nod from Nas on “Get Down,” a song from his God’s Son album, and urban legend, Fritz’ story doesn’t rise above a murmur.

Keeping 300–500 kilos a month below the whispers of the FBI is no easy feat. In historian David Farber’s book, Crack, he argues that drug dealers of Fritz’ magnitude think like corporate executives. Fritz’ obscurity can be credited to his business acumen of achieving the impossible, doing something that hasn’t been done.

One distinguishing fact about Fritz is that his crew consisted of only two people: friends Ace and Charles “Chucky” Caine. According to a 1992 New York Times report, Chucky was murdered by a kidnapping crew dubbed Wild Cowboys, after Fritz escaped a kidnapping attempt. The following year, nine members of the Wild Cowboys were indicted for three murders.

Most kingpins operate on a body politic. Popular underworld crews like The Supreme Team, The Chambers Brothers, or The Council had lieutenants, disciplinarians, and workers. Many drug organizations ran 8–12 hour work shifts — morning, afternoon, and night, and workers received their pay at the end of the work week.

In Nicky Barnes’ memoir, Mr. Untouchable, Barnes described how he strategically placed up to three people and cars at different locations to help transport his drugs from New Jersey or Queens back to his Harlem headquarters. One person never transported Barnes’ drugs from the pick-up location to the drop-off location. There were always at least three “layers” (people) between Barnes and his drugs.

As Farber shows in Crack, moving large-scale cocaine, running a crack house, or controlling a block requires precise planning, careful advertising, start-up money, and reliable workers.

“Fritz was ingenious in that he disregarded unwritten rules.”

Fritz was ingenious in that he disregarded unwritten rules. There was no crew, no crack houses, no intricate drug trafficking operation. His blueprint consisted of staying quiet, aloof from violence, and doing the opposite of what everyone else was doing.

During the ’70s, Fritz migrated with his family from Charleston, S.C. to Harlem, eventually settling at 109 112th Street. Queen Bee, a nurse-turned-drug drug lord, also lived in the same building. It was Bee who introduced Fritz to the dope game. While being supplied by Bee, the then-rookie hustler moved enough heroin to earn as much as $60,000 a week. But good things don’t last forever. QB had a cocaine addiction that hurt her behavior, eventually destroying her relationship with Fritz.

Breaking ties with Bee allowed Fritz to explore other options in the streets. While recovering from five gunshot wounds, resulting from a dispute over money Fritz owed to a supplier who’d given Fritz a bad batch of drugs, Fritz maintained a relationship with an individual from the Medellín Cartel.

Two years after nearly losing his life, Fritz received 15 kilos of cocaine from the cartel. Instead of assembling a crew to handle the drugs as most drug dealers do, Fritz gave the coke away on consignment. Consignment is risky, but Fritz was confident that he knew what he was doing, and he knew exactly who to give the cocaine to.

This prophetic foresight proved correct. It only took Fritz two weeks to get rid of the 15 kilos, earning the nickname “The Consignment King.” Soon thereafter, Ace was helping Fritz transport boxes of kilos from the Bronx to Harlem.

“Moving solo, or with no more than two people kept Fritz safe,” Holiday says. “The less people knew about what Fritz did, and how he moved, kept him alive and out of jail.”

As much as Fritz kept his circle small, he was in total harmony with everyone on 112th Street. Despite amassing millions of dollars, Fritz never moved out of his cramped apartment at 109 112th Street. This Robert Greene-like behavior (isolation is dangerous) distinguished Fritz from fellow heavyweights such as Kevin Chiles, Faison, and others who purchased elaborate homes in New Jersey or Long Island. Barnes, who is also from 112th Street, never left Harlem, but he bought and lived in a luxurious condo in Washington Heights.

“The building he lived in was his headquarters,” Ace says during our interview. “Everyone in that building worked for Fritz in some way.”

“The older folks in the neighborhood loved Fritz because he took care of them, gave money for groceries, and rent, money for their children’s back-to-school clothes,” Holiday said.

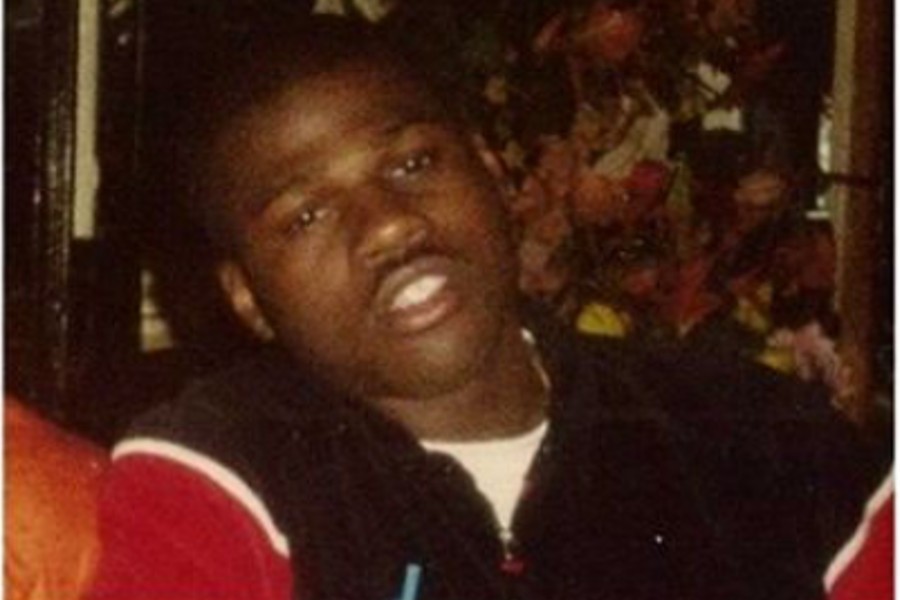

When Donnell Porter, brother of Rich Porter, was kidnapped and held for a $500,000 ransom, it was Fritz who gave Porter 30 free kilos of cocaine to get Donnell back. Unfortunately, Donnell was murdered before Porter could earn half a million in cash.

Along with larger-than-life individuals from Harlem, the sub-borough is known for its fashion. Dapper Dan, Cam’ron, and A$AP Rocky — all Harlem natives — have contributed to its prestigious fashion show. But not Fritz. As an example of his frugal habits, Fritz drove a modest Nissan Maxima. Meanwhile, his contemporaries cruised uptown avenues in cars costing at least $50,000. “Guys on 112th street were not known for being the most fly dudes in Harlem, or for driving the worst cars,” Sheila Harrison, Fritz’ half-sister said. “If you pulled up on the block with a flashy car, Fritz or one of the guys hustling would tell you to move it,” Harrison continued.

Fritz’ lowkey behavior didn’t stop wolves from attempting to eat off his labor. Robbery and extortion crews such as Preacher’s Crew, Lynch Mob, and Wild Cowboys instilled fear into Harlem’s underworld. And Fritz wasn’t exempt, either. Members of the Wild Cowboys made a few unsuccessful attempts on Fritz’ and his family’s life.

If you believe in honest diligence, then you probably have an issue with Fritz putting 300–500 kilos of cocaine into several neighborhoods. He played a role in drug addiction and countless armed robberies of dope boys and their families. Fritz easing the financial stresses of his neighbors doesn’t excuse the havoc that drugs brought into the community. However, the U.S. government backed the overthrow of Albania’s government, and Henry Kissinger signed off on Argentina’s Dirty War. Americans are rooted in contradictions.

According to Fritz’ sister Evelyn Simmons, Fritz’ life was cut short in 1991 after he was “poisoned.”

Fritz left behind several children, millions of dollars in cash, and a brownstone, which he never lived in.

“[I wrote The Harlem Plug] not glorifying the lifestyle he chose, but how he was put into a position to choose it as a means to seeking the American Dream,” Holiday says. “Some choices, although wrong, could have been overlooked as right, because of the community good that was done in an urban Robin Hood kind of way.”

Purchase The Harlem Plug here.

Darryl Robertson

Darryl Robertson is a freelance writer and research assistant for The New York Times. He is also a Justice-in-Education scholar and student at Columbia University. His research interests include hip-hop and understanding how the Black Power movement services its communities. He is also interested in understanding how social, geographical, and historical factors contribute to music.

Photo credit: 1) Amazon. 2) Wiki.

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact