The US government is throwing billions of dollars at building a network of charging stations to help boost the uptake of electric cars.

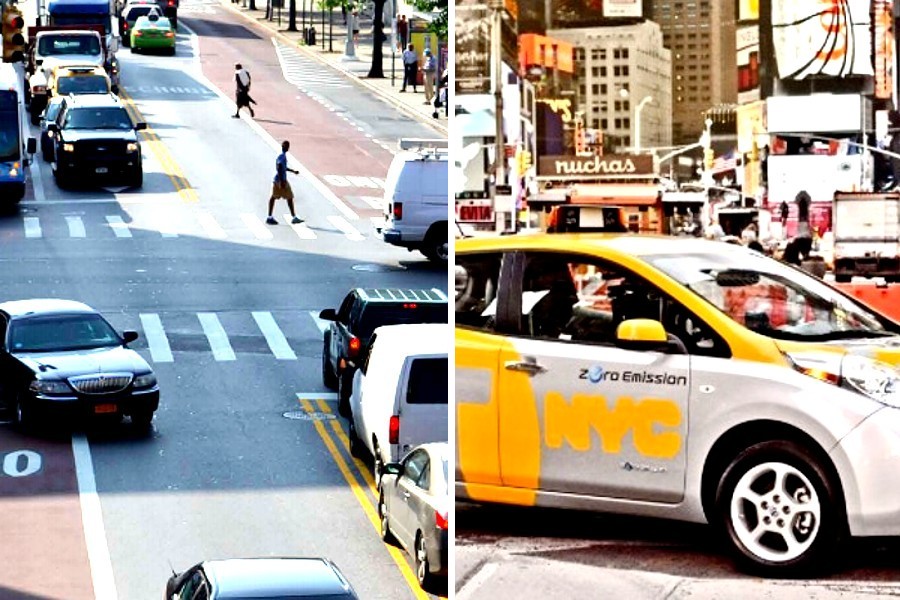

But some advocates worry the charging spots will bypass the disadvantaged communities from Hawaii to Harlem that have until now found electric vehicles well beyond their reach.

In Indiana, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) has complained that the state’s draft plan for the rollout of electric vehicle (EV) chargers has not properly consulted people of color, doesn’t specify any chargers in Black-owned businesses and focuses the new infrastructure on highways that cut through neighborhoods, rather than the neighborhoods themselves.

“We think the process is flawed and rigged against Black communities, Black businesses and other frontline communities of color,” said Denise Abdul-Rahman, Indiana state chair for the NAACP’s environmental justice program. “There’s been no real outreach here.

“We want the economic benefits of these chargers too, the modernized grids so we don’t have so many power outages, to get our school buses off diesel. We don’t want two Indianas and two Americas, one with roundabouts and clean air and charging stations and another riding around in fossil fuel cars and breathing in all the pollution. We want a just transition.”

Joe Biden’s administration has set a goal of having 500,000 fast-charging EV points across the US and last year’s infrastructure bill set aside $7.5bn to help with the first stages. A constraining factor to the popularity of EVs in the US, which comprise less than 5% of car sales, is driver anxiety over range, with many parts of the country lacking adequate charging infrastructure.

In February, states were asked to submit plans for charging networks to get $5bn of this federal money. However, the funding requires the chargers to be concentrated on highways or within a mile of a major intersection, which could leave out communities of people who have until now been unable to purchase EVs due to their relatively high cost.

Critics point out there is a long history of communities of color being overlooked when it comes to infrastructure decisions and it is unclear how a Biden administration vow, called Justice 40, to dedicate 40% of climate spending to disadvantaged areas will shape the rollout of the new chargers.

“Often, communities of color aren’t consulted until the latter stages where they are put into a situation where they are seen as enemies of progress, stalling things that need to happen,” said Rhiana Gunn-Wright, director of climate policy at the Roosevelt Institute and an architect of the Green New Deal.

Gunn-Wright said that the infrastructure bill and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which was passed this month and includes rebates to people to buy electric cars, are a “double-edged sword” as they provide needed funding but little direction as to how it is spent.

“The troubling thing about Justice40 is that it’s not been made clear if it applies to all or just certain programs,” she said.

“It needs to be made explicit so that localities have to take this into consideration. We are in a moment where the clean energy transition is happening, but if it’s not structured well the people who will benefit will be the wealthy, investors, and corporations who are able to lobby for things. That is a real fear.”

Some states have sought to rectify the EV imbalance, which has seen the vehicles largely become the domain of well-off white people, despite an uptick in overall interest. California’s energy commission, for example, has committed that half of the state funds for chargers will be assigned to disadvantaged communities.

“When you put these chargers on highways it’s hard to say you are benefiting the community, so we’ve pushed for those sort of commitments,” said Alvaro Sanchez, vice-president of policy at the Greenlining Institute in California. “We need to do this in a coordinated way so there aren’t charging deserts. But it’s going to be a priority for some states more than others, it will be a different experience in each place.”

Indiana plans to spend $100m on at least 44 EV chargers, potentially adding a further 28 if funds allow. The state department of transport insists it is committed to ensuring all people in the state will have fair access, predicting that 95% of people in disadvantaged communities will be within 35 miles (56km) of a charger.

“The federal government requirements are quite prescriptive, they don’t make it feasible to make off-highway placements that some communities are interested in,” said Scott Manning, deputy chief of staff at the Indiana Department of transport reports The Guardian.

“We had five public meetings and we offered one-on-one meetings, I think we feel pretty good about the effort in this process. But there is a long way to go in all this so I would welcome folks to get involved.”

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact