We thought this story by Chris Smith that orignally ran in the NYMagazine on November 3, 2010 would be informative as we head into the primary elections in June 2014.

We thought this story by Chris Smith that orignally ran in the NYMagazine on November 3, 2010 would be informative as we head into the primary elections in June 2014.

It’s a campaign-kickoff rally straight out of the playbook: festive red-white-and-blue posters, lapel buttons featuring the smiling candidate, a soundtrack of upbeat and strenuously unobjectionable tunes. Yet the prevailing feeling is of a living museum, a walking and talking historical diorama. Partly that’s because of the setting, a college campus’s courtyard flanked by gray, somber Beaux Arts slabs. Looming at the top of the exterior wall is a ribbon of chiseled names from the ancient explorers’ hall of fame—MAGELLAN, COLUMBUS, MARCO POLO, PTOLEMY—and of storied Native American tribes—ALGONQUIN, IROQUOIS, SIOUX.

What truly establishes the out-of-time vibe, however, is the composition of the crowd, a parade of Democrats past (Denny Farrell, Freddy Ferrer, C. Virginia Fields), present (Governor David Paterson), and eternal: Charlie Rangel, who, while closing in on his 80th birthday, is here to officially announce his run for a 21st term in Congress. “Let’s give Charlie Rangel one more term!” booms the master of ceremonies, State Assemblyman Keith Wright—who then pauses awkwardly, seeming to realize that he’s hinted at Rangel’s retirement. “He can have as many as he wants, as far as I’m concerned!” Wright shouts more loudly.

Yet even in this show of force and confidence by the uptown political Establishment are hints of the changes shaking their world. First is the location: Though Rangel is the dean of black city politics, he’s come to Boricua College in Washington Heights, one of the fast-growing Latino sections of his district. The second, more subtle sign comes when Rangel ends his rambling, combative speech and calls for all the elected officials and Democratic functionaries to join him onstage. It makes for a happy, crowded photo—and leaves about 25 lonely people in the audience, mostly reporters and small children.

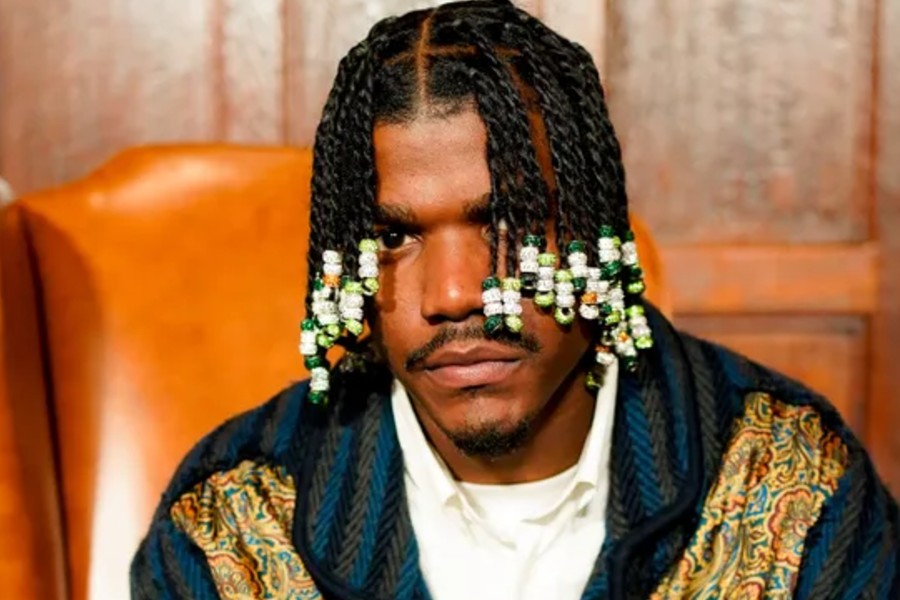

And Basil Smikle. Throughout the rally, Smikle’s hovered at the edge of the crowd, smiling and shaking hands; a political consultant and adjunct Columbia professor, he is now a candidate for the State Senate, running against incumbent Democrat Bill Perkins, who has become the prime target of Harlem’s charter-school backers. Yet Smikle also represents a challenge to Rangel and the rest of the Harlem Establishment. He is 38 and was educated in the Ivy League, not the neighborhood clubhouses. Rangel—resplendent in a white sport coat and matching blue tie and pocket square, with a gold pin cinching his collar—arrived today by Town Car. Smikle wears a navy pin-striped suit with no tie and travels by motorcycle.

Smikle is hardly a radical. He has spent his entire adult life working as a strategist for mainstream New York Democrats. Yet Smikle can credibly claim to be an “insurgent,” which is a testament to the insularity of the old guard he’s threatening and to the new forces roiling the Harlem political order. “This uneasiness in Harlem comes because [the old guard] hasn’t passed the torch, and so now, people are trying to seize it,” Smikle told me earlier. “They’re saying, ‘You gotta wait your turn.’ No, I don’t want to wait my turn. Did you tell that to Barack? Did he wait his turn? We can do it whether they say so or not.”

That boldness is also a distant echo of the man whom Charlie Rangel beat to get into Congress, the man who launched the Harlem political epic more than 60 years ago.

The end of an era has been declared repeatedly ever since the death, in December, of Harlem political patriarch Percy Sutton and the political demise of Governor Paterson this winter. Yet the more accurate, and complex, tale is an unfinished one. It starts in 1944, when a brilliant, singular personality, Adam Clayton Powell Jr., became the first person elected to represent a congressional district created to empower central Harlem. By 1970, Powell was sick with cancer and brooding on a Caribbean island, and was knocked off by Charlie Rangel, who has become the consummate Washington insider, steering tens of millions of dollars to the district and making Harlem a force in city elections. Now, though, in an echo of the financial and legal messes that brought down Powell, an ethics investigation has forced Rangel to give up his chairmanship of the House Ways and Means Committee; last week, a congressional panel accused him of multiple ethics violations.

Racial politics in New York and nationally have shifted to the point where the machine model that served Rangel so well has grown creaky. No one knows what the new order will look like, but the struggle to define it is under way in the cradle of black politics. The battle isn’t simply to follow Rangel in Congress—the district’s next congressman could as easily be white or Latino as black—but to determine what style of politics will control Harlem in the future: a revitalized, updated clubhouse, a reform movement in the Obama mold, or perhaps something in nobody’s mold, like the freewheeling pioneer who’s the father of Harlem politics.

The Reverend Adam Clayton Powell Sr. moved his expanding congregation from West 40th Street to Harlem in 1923. His son Adam Clayton Powell Jr. turned the Abyssinian Baptist Church into a social and religious phenomenon during the late thirties, then crossed over, becoming the first nationally important black preacher-politician. Titles don’t come close to doing Powell justice, however. Imagine a man who combines the political intellect of Barack Obama with the pop-star appeal of Jay-Z. Or perhaps a melding of Martin Luther King Jr. and Muhammad Ali. With more rakish style than any of them.

At the height of his career, Adam Clayton Powell Jr. could pack churches in St. Louis, Tampa, or Los Angeles by visiting to deliver a Sunday-morning sermon. As a congressman, he created just as much of a stir touring Europe with his second wife, the singer and jazz pianist Hazel Scott, drinking with aristocrats and hipsters in the clubs of Paris, Edinburgh, and Munich—and the next day quizzing generals and black soldiers at the nearest American military base.

“He had no real clout on the Hill, but he traveled the world and became an American ambassador without portfolio. It made him hugely popular, nationally and internationally. He was the most voluble, visible, widely heard black American, a tremendous hero in the black community.”

Powell’s long public presence, from the late thirties to 1972, was overstuffed with drama, and he had two overlapping periods of enormous significance in American life—one of popular influence and one of political weight. “His greatest cultural moment was in the fifties,” says Wil Haygood, who wrote King of the Cats, the definitive Powell biography. “He had no real clout on the Hill, but he traveled the world and became an American ambassador without portfolio. It made him hugely popular, nationally and internationally. He was the most voluble, visible, widely heard black American, a tremendous hero in the black community.”

Part of what gave Powell such weight was that he represented Harlem, the capital of black America. Harlem was ahead of the country in everything from music to racial progress, and so was Powell, who was a provocative advocate for civil rights beginning in the mid-forties. His practical power soared when LBJ took over the White House. In 1961, Powell became chairman of the House Education and Labor Committee. “He kept an aggressive social agenda at the forefront of the American consciousness, and that hadn’t been done since FDR’s New Deal,” Haygood says. “To put hunger, the minimum wage, and food stamps on the front pages was unique and very forward-looking. Inside the House, he knew which strings to pull, who to reach on the phone at midnight, how to cajole. Without Powell, the War on Poverty wouldn’t have been nearly as successful.”

Yet the congressman’s race, his swagger, and his inattention to financial rules caused a nonstop run of controversy. He battled tax-evasion and libel charges, and in 1967, Powell was expelled from Congress, ostensibly for having his third wife on the congressional payroll and for misusing airline tickets; two years later, he was reinstated by the Supreme Court.

Powell’s legacy includes the raising of living standards across the country and the legitimizing of black voices in the national political conversation. Yet he grew increasingly distant, physically and emotionally, from his New York district. His charisma and cunning took him far, but he wasn’t interested in creating a political structure that would survive him. Two ambitious young politicians were more than happy to step into the void.

Charles Rangel and Percy Sutton met in a printer’s shop, picking up campaign posters in 1963. Each had a highly developed sense of what could be accomplished with politics, both in terms of doing well and doing good.

Rangel had grown up poor on Lenox Avenue, served heroically with the Army during the Korean War, then got his law degree at St. John’s. One of Rangel’s first lessons in politics came when he successfully appealed to Tammany Hall’s boss, Carmine DeSapio, to save his grandfather’s job as an elevator operator. Sutton grew up in Texas, where his father, a high-school principal, owned a collection of small businesses. Sutton served in World War II, then came to New York for law school; setting up a legal practice in Harlem, he spotted Malcolm X on a street corner and introduced himself to the Muslim minister as Malcolm’s new lawyer. Sutton was also on the front lines of the civil-rights movement, getting arrested in Alabama and Mississippi as a Freedom Rider. Yet he saw a path to local power in the political clubhouses of Harlem. Sutton eventually held offices as high as Manhattan borough president, but his great gift was as a strategist.

Rangel and Sutton started out as “reformers” eager to take on Harlem’s political regulars. But they soon found themselves studying at the knee of the legendary J. Raymond Jones. “The Fox” had learned Tammany’s tactics from the inside as its man uptown.

Rangel and Sutton started out as “reformers” eager to take on Harlem’s political regulars. But they soon found themselves studying at the knee of the legendary J. Raymond Jones. “The Fox” had learned Tammany’s tactics from the inside as its man uptown. In 1958, Jones aligned himself with Powell to help the congressman beat back a challenge from Tammany. Then the Fox set about creating an uptown version of Tammany. He saw talent in the younger ranks, many of them vets who’d returned to school on the G.I. Bill and now were looking for challenges. Jones taught Rangel and Sutton how business was really done, using the duo as Harlem operatives to help reelect Robert Wagner in a bruising 1961 mayoral campaign.

Rangel soon won public office himself, and as a state assemblyman in the mid-sixties, he became a favorite of Governor Nelson Rockefeller. In late 1969, Rockefeller asked Rangel to go to Bimini and see if Powell could be coaxed out of his self-imposed exile—Rockefeller thought it would help him with the black vote. Powell, suspicious, kept Rangel waiting. When he finally sat down to talk, it was in a dim bar, the congressman surrounded by island pals and ordering up rounds of drinks. Rangel has always claimed he went to Bimini with no notion of running against Powell, but as the awkward conversation wound down and it became clear Powell had little interest in returning to Harlem and Washington full-time, Rangel warned that he might become one of the candidates challenging the incumbent. “Do what you have to do, baby,” Powell replied, patting Rangel on the cheek patronizingly. Then he left, sticking Rangel with the bar tab.

One year later, Rangel defeated Powell in the Democratic primary by just 150 votes. Much of the margin came from the white West Side segment of the district.

The Harlem that first elected Adam Clayton Powell Jr. in the mid-forties was a destination. It was the Harlem of W.E.B. DuBois, Roy Wilkins, Joe Louis, Duke Ellington, and Langston Hughes, where money flowed in after World War II and a new freedom was in the air, with the desire for real equality close behind it. Powell was a perfect expression of the neighborhood’s exuberance and restlessness, leading brave boycotts and picket lines that broke employment color lines from department stores to Con Ed.

Rangel, as a neophyte congressman, represented the seventies Harlem of James Brown and Frank Lucas, an increasingly poor and tense neighborhood that was shedding its middle class as it slid from the preeminent black enclave to an impoverished center of urban ills. Rangel’s task has been much different from Powell’s. So has his style. “Adam didn’t have any friends. He had a whole lot of followers that loved him,” Rangel says, in his deliciously rascally voice. “When I got to Washington, I found out that he acted like he was a very lonely man. After the receptions, he would stay at one place on Logan Square, he would listen to music, he would prepare for his sermons. And when he wasn’t alone, he was with tens of thousands of people.”

Rangel is plenty blunt: “I don’t see why Richard Blumenthal’s campaign and his political career isn’t just deep-sixed,” he tells me after the Connecticut Democrat was caught inflating his military record. “It seems to me he would be cooked meat.” He’s also taken plenty of moral stands, on everything from apartheid to the draft. But he became a leader in Washington by pragmatically making friends on both sides of the aisle, building consensus and coalitions while accumulating seniority and moving up the ladder, slowly. “Charlie wanted to live in Congress,” says Bill Lynch, the (now deceased) Harlem political consultant who helped elect David Dinkins mayor and has long advised Rangel. “He understood that whole process down there, the horse-trading that went on down there, the backslapping—he was the best at it. He loved it. We used to go off to the fat farms of Pritikin together, and I thought we’d sit by the pool—but the whole time he was on the phone to his office.”

Powell carried with him the overtones of the civil-rights struggle and, for all his insider connections, a countercultural image. Rangel was from the start a power player, and his tactical sense fit perfectly with the changing times and a changing Harlem. Sutton proved the ideal partner, analyzing every possible angle and making sure the Harlem machine assembled a deep and loyal roster of county committeemen, district leaders, and community-board members.

“The zone became an alternative way to invest in Harlem. Residents were desperate for retail, and it supported small businesses like Amy Ruth’s and big things like Harlem USA and Target. It’s a huge part of Charlie’s legacy.”

Together with David Dinkins, then the city clerk, and Basil Paterson, a Hugh Carey–era New York secretary of State, they became known as the “Gang of Four,” a quartet that gave black New Yorkers a louder voice in public-policy issues and a larger share of the patronage pie. Whatever its flaws—millions of public dollars were sunk into a Sutton-Rangel deal to prop up the Apollo Theater—the gang’s tactics brought real rewards. Rangel, in the mid-nineties, spearheaded legislation to create the Upper Manhattan Empowerment Zone, steering $300 million in public development funds to the neighborhood. “There had been so many cycles of growth in the city, and they all passed Harlem by, because there was no way for an outsider to come in and do business in Harlem without having to deal with a lot of gatekeepers,” says Ester Fuchs, a Columbia University professor of public affairs who helped write the original empowerment-zone proposal. “The zone became an alternative way to invest in Harlem. Residents were desperate for retail, and it supported small businesses like Amy Ruth’s and big things like Harlem USA and Target. It’s a huge part of Charlie’s legacy.”

Another signature Rangel accomplishment, the low-income-housing tax credit, has helped rehabilitate and develop thousands of units of inexpensive housing, not just in Harlem but also across the country. Yet today many longtime Harlem residents complain bitterly about gentrification and the explosion in rents and housing prices, while the local public schools continue to lag. To critics, the Gang of Four seems to have existed merely to perpetuate its own power. Fuchs takes a broader view. “They came out of the civil-rights era, and their elections in and of themselves were significant,” she says. “Then they had to deal with the basic decline of the American city and the concentration of poverty in black and low-income neighborhoods. When politics was about trying to get federal and state dollars, these guys fought as hard as anybody. David Dinkins is responsible for the beginning of the reduction in crime, and when the tide starts to turn, these four guys were there making sure investment came to Harlem. There was something in Harlem to rebuild and redevelop because of these guys; in a lot of neighborhoods, there’s nothing. In the periods of positive transformation, Harlem is the center. It’s not Brownsville or Bed-Stuy or Melrose. People still want to put their money and their ideas to work in Harlem, and they deserve credit for that.”

“They’re saying, ‘You gotta wait your turn,’ ” says Basil Smikle. “No, I don’t want to wait my turn. Did you tell that to Barack? Did he wait his turn?”

The gang’s also displayed a genius for containing intramural disputes. “What’s been characteristic of the Rangel-Sutton dynasty years—and was more Percy’s achievement than anybody else’s—is teamwork, instead of the divisions of the Powell years,” Rodney Capel says. Capel, a political consultant, straddles the old- and new-guard camps. His father is Rangel’s longtime chief of staff, and he is a close friend of Smikle’s. Capel, 38, has had a prime vantage point on the downside of the gang’s concentration of power: that it stifled a generation of aspiring leaders. “The biggest thing you’re seeing now,” Capel says, “is that unity breaking up. Everyone’s doing their own thing. Everyone’s shooting at each other, and it’s uncharacteristic of what we’ve seen for twenty years.”

Harlem’s second-generation black politicians have struggled mightily with their inheritance. David Paterson, who alternately embraced and spurned the Gang of Four’s help on his rise through the State Legislature, gained statewide office by defying his elders’ wishes and accepting a spot as Eliot Spitzer’s lieutenant governor. When Paterson was stunningly elevated to governor, the office Paterson’s father once seemed destined to occupy, he had another chance to make them all proud—and instead stumbled so badly that he was forced to quit the 2010 race for governor.

Paterson, as a lame duck, has rebounded somewhat by getting tough on the state budget. Adam Clayton Powell IV is still searching for redemption. Powell IV, also known as Adamcito, is the son of Powell Jr. and his third wife, who was Puerto Rican. One afternoon this summer, Powell IV is in his State Assembly district office, on East 116th Street, but he wants to talk about his quest to unseat Rangel. Election rules require keeping campaign business separate from his day job representing East Harlem in Albany, so he leads the way out onto the sidewalk, five paces down the street, then up two narrow, twisting flights of stairs. Here is the Powell for Congress campaign office: a card table and a couple of folding chairs.

It’s always good to pay attention to the arcana of election law, and Powell has a particular sensitivity to judicial details. In 2004, he was accused of rape by two different women; no charges were filed. In 2008, he was arrested on the West Side Highway and charged with drunk driving. Earlier this year, a jury acquitted him of driving while intoxicated but found him guilty of driving while impaired.

Now Powell, 48, has declared the fight of his life, a bid not simply to move up in electoral prestige but to avenge the loss that ended his legendary father’s political career. The stakes are significant, the story lines rich. But IV seems, well, kind of bored. “I represent the people, not the clubhouse,” he says languidly. “There’s something else important at play here. Rangel is not asking for people’s votes for the next two years. There’s rampant speculation he’s trying to win and then manipulate the process to choose his successor.” Speculation? Can he back it up with any specifics? “Everyone is talking about it,” he says. “Everyone knows.”

Several blocks northwest of the campaign office is a statue of Powell’s father, depicted as he strides gallantly forward, a bronze coat billowing behind. It’s in the plaza of the Adam Clayton Powell Jr. State Office building, where for months the sculpture was hidden behind plywood to protect it from repair work on the drab building.

One of the better cases for Harlem political continuity sits upstairs, in an office on the ninth floor. Keith Wright isn’t a visionary. But he has seen a lot of politics in his 55 years. A state assemblyman since 1992 and the leader of Manhattan’s Democrats since last year, Wright also comes from Harlem royalty, though with a twist. His father, Bruce, was a judge, an intellectual, and a fiercely combative man—qualities that earned him the nickname “Turn ’Em Loose Bruce” from conservative critics. Growing up in that household—and riding a bus to the Ethical Culture School with future powers like Patti Harris, Mayor Bloomberg’s chief lieutenant, and Nicole Seligman, a corporate lawyer and Joel Klein’s wife—provided Wright with an early education in Realpolitik. “My father was one of the only judges who was not a member of a party,” he says. “But he was Percy Sutton’s lawyer, and Percy said, ‘I can’t pay you, Bruce, but I’m gonna make you a judge. But before I make you a judge, I have to make my brother a judge.’ And that’s exactly what happened.”

Wright, who recently steered a domestic-workers’-rights bill into state law, has decorated nearly every inch of his office’s walls with plaques and photographs. One stands out, a black-and-white shot of five grinning young men in a restaurant: David Paterson, Scott Stringer (who’s white), Adam Clayton Powell IV, Geoffrey Garfield, and Wright. It was 1992, and they’d gathered in an Upper West Side Greek restaurant to plot Stringer’s run for the State Assembly. The relationships have grown considerably more complicated in the eighteen years since then. “That picture was taken before Keith went over to the dark side,” Powell says. “He’s a nice guy personally, but the insiders are trying to manipulate the process so Rangel wins this fall and then hands the job to Keith.” Wright dismisses the conspiracy theorizing as the desperation tactics of a long-shot candidate. “Adam ran against Charlie in ’94, got his clock cleaned, and I suspect the same thing will happen this time.”

Among the declared rivals to Rangel is Vince Morgan, a 41-year-old community banker and former aide to Rangel who grew up in Chicago and is a cousin of Harold Ford Jr. Morgan argues that Rangel is out of touch with Harlem’s grassroots concerns about education, jobs, and housing. “Over 40 years, there’s a wider and wider chasm between the people of the district and their representative in Washington,” Morgan says. “We have a tendency in our community to wait for the retirement service or the memorial service to start planning for the future. I don’t want to put the people of this district in harm’s way because Mr. Rangel’s ego is keeping him in office a little bit too long.”

Wright is willing to wait for Rangel to step aside. He claims that the old order, with new blood, can maintain Harlem’s distinctive power while delivering wider benefit. “The so-called demise of the Harlem political Establishment—I think that’s coming from other places,” Wright says. “The black elected officials from Brooklyn are always envious of Harlem, because they have more black folks out there but Harlem gets all the ink. Politics is not glamorous, and it’s still a chess game, and you need a sense of history—of Harlem’s history—to succeed at it for people here. I don’t think a lot of the younger folks have the patience to learn the game or an appreciation of what Harlem still means to black America.”

“Somebody that puts together the new blacks and the Latinos and the whites is going to be able to flip the whole Harlem leadership.”

Increasingly it means nostalgia. Rangel’s district was 63 percent black when he was first elected; today it’s 37 percent black and 46 percent Hispanic. “Bensonhurst ain’t Bensonhurst anymore, and guess what? Harlem ain’t Harlem anymore, either,” says the Reverend Al Sharpton, who made the neighborhood his base of operations twenty years ago and is still resented as an interloper by many of the clubhouse stalwarts. “But a lot of Harlem politicians are just trying to hold on to something that’s not there anymore,” Sharpton says. “Somebody that puts together the new blacks and the Latinos and the whites is going to be able to flip the whole Harlem leadership.”

In Harlem, even the choice of lunch spot is political. Basil Smikle has picked Londel’s because the chicken wings and the crab cakes are terrific—but also because Londel’s isn’t Sylvia’s, the tourist attraction and bastion of old Harlem. A political junkie from the time he was growing up in the Bronx, Smikle graduated from Cornell, went to work for the Upper Manhattan Empowerment Zone, and moved to Harlem while studying for a master’s at Columbia. After stints working for Ferrer and Hillary Clinton, Smikle set up shop as a political consultant, and last year he became one of the legions hired to help Mike Bloomberg win a third term.

That professional pedigree, of course, isn’t what Candidate Smikle wants to emphasize. “My parents came here in 1970 from Jamaica,” he says, “and my father worked multiple jobs; there was a time we were on public assistance. It was never easy. So while I have this blue-chip education, I don’t have a blue-chip background. Both of those will be beneficial in making my case to voters, and in the kind of public official I’d be.”

His opponent, Bill Perkins, is a favorite of the teachers union and has been highly skeptical of the wave of charter schools opening in Harlem. Smikle’s campaign has enjoyed donations from some of the biggest charter-school operators, but he’s eager to insist he isn’t a one-issue wonder. “Look, charters are the galvanizing issue in Harlem, and clearly people are taking sides, but it’s not the only issue,” Smikle says. “The charters, because of my position on them, I’ve immediately lost the majority of union support. And it’s unfortunate. Because I’ve supported unions all my career, my parents are union members—one of them still is; my mother’s been a UFT member for 26 years.”

Smikle sees his candidacy in grander terms than spats over school reform. “I’m not Barack, and I’m not Cory Booker, but in many ways this is the same race,” Smikle says. “The same race, but in Harlem. I’m going to be painted as an outsider, as the guy who spends most of his time around white folks and big money—which is not true, but whatever. And you know what? The majority of the new residents of Harlem have the same type of socialization.”

Kevin Wardally has heard this kind of talk before. “We call it the ‘young, gifted, and black’ syndrome,” he says with a sly smile. “People from our community get an opportunity, go to Harvard or Yale, then come back to Harlem and say, ‘You know what? I should be congressman because I’m smart and I went to Yale Law and I worked on Wall Street for a couple of years. I know more than the guys in these seats, and I should run.’ ” Wardally shakes his head. “But those folks didn’t win.”

…people who think that Charlie and everybody else has gotta go forget that the machine helps people’s lives. I sat at the front desk when I worked in Charlie’s office, and I got people’s lights turned back on. And got their heat turned back on. When people had problems with food stamps and immigration, we helped them. These folks out here are not an organizing tool for you to get into office. That’s why these new guys always lose.

Wardally knows plenty about the realities of winning. He has been Bill Lynch’s right-hand man for ten years, though his roots in Harlem politics run far deeper. “Bill’s wife was my kindergarten teacher, and my mother was a community organizer who was close to Dorothy Height during the Poor People’s Campaign,” he says. At 38, Wardally is of Smikle’s generation, and they’ve been friendly for years. But Wardally is of a different vintage when it comes to his political worldview. “Look, I come from the clubhouse model: I’ve been a member of a political club since I was 14 years old,” he says, sitting his office, one block up the street from Sylvia’s. “And maybe one day I’ll be wrong. But these people who think that Charlie and everybody else has gotta go forget that the machine helps people’s lives. I sat at the front desk when I worked in Charlie’s office, and I got people’s lights turned back on. And got their heat turned back on. When people had problems with food stamps and immigration, we helped them. These folks out here are not an organizing tool for you to get into office. That’s why these new guys always lose.”

Wardally’s mission now is not just to give Rangel another term in Congress but to restore Rangel’s reputation. He’s especially incensed by a 2008 Post front-page photo that showed the portly congressman asleep on a beach chair. “It’s sad. There’s no criminality here—clearly no criminality—it’s more paperwork than anything else,” Wardally says about the ethics accusations against Rangel. “Yet when folks go home to their low-income housing, they’re not going to remember to thank Charlie Rangel, but they’re going to remember a picture of him on a beach because a bastard reporter chose to take a picture. He can’t have a vacation like everyone else can?”

Rangel has consistently denied any wrongdoing. He bristles at mentions of the ethics investigation, pointing out—correctly—that much of the fuss was fomented by a conservative group. “I stepped aside [as Ways and Means chair] because Republicans were making Rangel the issue instead of dealing with health care,” he says. Yet he compounded the trouble with risible explanations of his failure to pay federal taxes on a Caribbean villa. More disturbing are allegations that he solicited donations to CCNY’s Rangel Center for Public Service from an oil company lobbying for a tax break.

Plenty of other politicians would have enriched themselves far more during a 40-year career, and Rangel rejects any parallel to his predecessor’s scandals. “I don’t see it the same way,” he says. “There is a comparison, that Adam was under severe attack by the newspapers, but he contributed to that by staying away from the Congress and the community. So I don’t think I am as vulnerable as Adam was, but I tell you one thing, I’m making clear that I’m not going to be caught unprepared, and I am preparing for the roughest type of campaign.”

The dean of New York’s congressional delegation will get his retirement, forced or voluntary, soon enough. The machine Charlie Rangel helped run is also coming to a fitful end, having opened up educational and economic doors for the new class of eager young leaders who don’t feel the need to follow the traditional paths. “This is what they wanted us to be,” Basil Smikle says. “They wanted to see us in corporate America, having opportunities. All we’re saying is we want to come back and find a way to be helpful.” Which is a nice sentiment and a worthy goal. Harlem’s political old guard, for all its imperfections, delivered more than simply good intentions

Has anything changed? Does Harlem need change? What do you think is the answer? Please share you comments with us below.

Related articles

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact