The black clergymen who had been summoned to Harlem’s Mount Olivet Baptist Church for an emergency meeting on the morning of Monday 10 September 1906, arrived in a state of outrage.

The black clergymen who had been summoned to Harlem’s Mount Olivet Baptist Church for an emergency meeting on the morning of Monday 10 September 1906, arrived in a state of outrage.

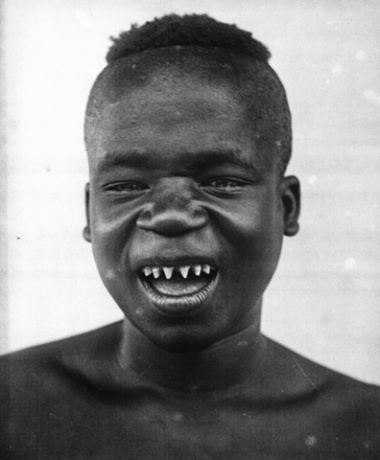

A day earlier, the New York Times had reported that a young African man – a so-called “pygmy” – had been put on display in the monkey house of the city’s largest zoo. Under the headline “Bushman Shares a Cage With Bronx Park Apes”, the paper reported that crowds of up to 500 people at a time had gathered around the cage to gawk at the diminutive Ota Benga – just under 5ft tall, weighing 103lb – while he preoccupied himself with a pet parrot, deftly shot his bow and arrow, or wove a mat and hammock from bundles of twine placed in the cage. Children giggled and hooted with delight while adults laughed, many uneasily, at the sight.

In anticipation of larger crowds after the publicity in the New York Times, Benga was moved from a smaller chimpanzee cage to one far larger, to make him more visible to spectators. He was also joined by an orangutan called Dohang. While crowds massed to leer at him, the boyish Benga, who was said to be 23 but appeared far younger, sat silently on a stool, staring – sometimes glaring – through the bars.

The exhibition of a visibly shaken African with apes in the New York Zoological Gardens, four decades after the end of slavery in America, would highlight the precarious status of black people in the nation’s imperial city. It pitted the Harlem “coloured” ministers, and a few elite allies, against a wall of white indifference, as New York’s newspapers, scientists, public officials, and ordinary citizens revelled in the spectacle. By the end of September, more than 220,000 people had visited the zoo – twice as many as the same month one year earlier. Nearly all of them headed directly to the primate house to see Ota Benga.

His captivity garnered national and global headlines – most of them inured to his plight. For the clergymen, the sight of one of their own housed with monkeys was startling evidence that in the eyes of their fellow Americans, their lives didn’t matter.

On that Monday afternoon, a small group of ministers, led by the Reverend James H Gordon – then hailed by the Brooklyn Eagle as “one of the most eloquent Negroes in the country” – boarded a train to the zoological gardens, better known as the Bronx Zoo. At the gleaming white beaux-arts-style primate house, they spotted Ota Benga ambling within a cage, in the company of Dohang, the orangutan. A sign outside the cage read:

On that Monday afternoon, a small group of ministers, led by the Reverend James H Gordon – then hailed by the Brooklyn Eagle as “one of the most eloquent Negroes in the country” – boarded a train to the zoological gardens, better known as the Bronx Zoo. At the gleaming white beaux-arts-style primate house, they spotted Ota Benga ambling within a cage, in the company of Dohang, the orangutan. A sign outside the cage read:

The African Pygmy, Ota Benga

Age, 23 years. Height, 4 feet 11 inches.

Weight 103 pound. Brought from the Kasai River,

Congo Free State, South Central Africa,

By Dr Samuel P Verner.

Exhibited each afternoon during September

The ministers’ attempts to communicate with Ota Benga failed but his palpable sadness and the sign stoked their indignation. “We are frank enough to say we do not like this exhibition of one of our own race with the monkeys,” Gordon fumed. “Our race, we think, is depressed enough, without exhibiting one of us with apes. We think we are worthy of being considered human beings, with souls.”

William Temple Hornaday, the zoo’s founding director and curator, defended the exhibition on the grounds of science. “I am giving the exhibition purely as an ethnological exhibit,” he said. The display, he insisted, was in keeping with the practice of “human exhibitions” of Africans in Europe, breezily evoking the continent’s indisputable status as the world’s paragon of culture and civilisation.

Unrepentant, Hornaday declared that the show would go on just as the sign said, “each afternoon during September” or until he was ordered to stop it by the Zoological Society. But Hornaday was not some rogue operator. As the nation’s foremost zoologist – and a close acquaintance of President Theodore Roosevelt – Hornaday had the full backing of two of the most influential members of the Zoological Society, both prominent figures in the city’s establishment. The first, Henry Fairfield Osborn, had played a lead role in the founding of the zoo and was one of the era’s most noted paleontologists. (He would later achieve fame for naming Tyrannosaurus rex.) The second, Madison Grant, was the secretary of the Zoological Society and a high-society lawyer from a prominent New York family. Grant had personally helped negotiate the arrangement to take Ota Benga.

The clergymen had no success at the zoo, and left the park vowing to take up the matter the next day with the city’s mayor. But their complaint did catch the attention of the New York Times, whose editors were dismayed that anyone might protest against the display.

“We do not quite understand all the emotion which others are expressing in the matter,” the paper said in an unsigned editorial. “Ota Benga, according to our information, is a normal specimen of his race or tribe, with a brain as much developed as are those of its other members. Whether they are held to be illustrations of arrested development, and really closer to the anthropoid apes than the other African savages, or whether they are viewed as the degenerate descendants of ordinary negroes, they are of equal interest to the student of ethnology, and can be studied with profit.”

The editorial said it was absurd to imagine Benga’s suffering or humiliation. “Pygmies,” it continued, “are very low in the human scale, and the suggestion that Benga should be in a school instead of a cage ignores the high probability that school would be a place of torture to him … The idea that men are all much alike except as they have had or lacked opportunities for getting an education of books is now far out of date.”

In the sober opinion of progressive men of science, Benga’s exhibition on the hallowed grounds of the New York Zoological Gardens was not mere entertainment – it was educational. They believed Benga belonged to an inferior species; putting him on display in the zoo promoted the highest ideals of modern civilisation. This view had, after all, been espoused by generations of leading intellectuals. Louis Agassiz, the Harvard professor of geology and zoology, who at the time of his death in 1873 was arguably America’s most venerated scientist, had insisted for more than two decades that blacks were a separate species, a “degraded and degenerate race”.

Two years before Ota Benga arrived in New York, Daniel Brinton, a professor of linguistics and archaeology at the University of Pennsylvania, had used his farewell address as president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science to attack claims that education and opportunity accounted for varying levels of achievement among the races. “The black, the brown, and the red races differ anatomically so much from the white, especially in their splanchnic organs, that even with equal cerebral capacity they never could rival its results by equal efforts,” he said.

The dominant force of these ideas – embedded in science, history, government policies, and popular culture – would render Benga’s discomfort and humiliation in a monkey-house cage incomprehensible to the vast majority of those who witnessed it.

That it could have occurred in America’s most cosmopolitan city in the 20th century would seem enough cause for astonishment. But what appears on the surface to be a saga of one man’s degradation – a shameful spectacle – is, on closer inspection, the story of an era, of science, of elite men and institutions, and of racial ideologies that still endure today. Worse yet, Benga left no written account of his own life – and others have since filled the gap with denials, conspiratorial silence, half-truths, and even flagrant deception. But it is possible to return to the archives – to letters, anthropological field notes, and contemporaneous accounts – and to reconstruct the real circumstances by which Ota Benga, before the age of adulthood, was stolen from his home in central Africa and brought to New York City for the amusement, and education, of its residents.

Samuel P Verner, the self-styled African explorer who took Benga from Congo, told a New York Times reporter that neither he nor the park would profit from the exhibition. “The public,” he insisted, “is the only beneficiary.” Verner further claimed that Benga was there of his own volition: “He is absolutely free … The only restriction that is put upon him is to prevent him from getting away from the keepers. That is done for his own safety.

“If Ota Benga is in a cage,” he reasoned, “he is only there to look after the animals. If there is a notice on the cage, it is only put there to avoid answering the many questions that are asked about him.” Verner said that he regretted if any feelings had been hurt – but his only concession was to assure the reporter, in an apparent nod to Christian sensitivities, that care would be taken not to exhibit Benga on Sundays.

Hornaday was so pleased by the attendance figures at the zoo that he quietly began making plans to keep Benga on display through the autumn, and possibly until the following spring. For his part, he told reporters that Benga had been put in the primate house “because that’s the most comfortable place we could find for him”. In response to such claims, Reverend Gordon publicly offered to house Benga at his own orphanage for black children. But he would first have to secure Benga’s release.

On Wednesday morning, the ministers headed to city hall to meet New York’s erudite mayor, George Brinton McClellan, who also served as an ex-officio member of the Zoological Society. The clergymen had planned to appeal for Benga’s immediate release, but they did not get past the reception area; the mayor’s secretary said he was too busy to meet them.

On Wednesday morning, the ministers headed to city hall to meet New York’s erudite mayor, George Brinton McClellan, who also served as an ex-officio member of the Zoological Society. The clergymen had planned to appeal for Benga’s immediate release, but they did not get past the reception area; the mayor’s secretary said he was too busy to meet them.

“Certainly the mayor, the executive head of the city, may put a stop to an indecent exhibit,” Gordon complained to a reporter. The ministers were told to see Madison Grant, the secretary of the Zoological Society, but at his Wall Street law office, he was similarly unhelpful. He told them that Benga would be at the zoo for only a short time, and that Verner would soon take him to Europe.

When Gordon returned to the zoo that afternoon, he found Benga, with a guinea pig, in a cage surrounded by several hundred spectators. “The crowd seemed to annoy the dwarf,” the New York Times reported in an article published the following day. By this point, Gordon had sought the assistance of Wilford H Smith, who had recently been the first black lawyer to successfully argue a case before the US supreme court. After consulting with the city’s attorney, Smith agreed to appeal to a court for Benga’s release – and John Henry E Millholland, a wealthy white New Yorker who had founded the Constitution League to protest against the disenfranchisement of blacks in the south, agreed to finance the case.

The combination of Smith’s stature, Milholland’s financial backing, and the threat of a lawsuit undoubtedly got the attention of the Zoological Society’s officials. Hornaday’s response, however, was minimal: on the advice of Osborn, he quietly removed the sign outside Benga’s cage. But spectators continued to flock to the monkey house, hoping to steal a glimpse of the “pygmy”.

The story of Ota Benga’s captivity at the Bronx Zoo began in 1903, when Verner – an avowed white supremacist from a prominent South Carolina family – heard about plans for the 1904 World’s Fair in St Louis. The fair’s organisers hoped to celebrate American imperialism, and map human progress “from the dark prime to the highest enlightenment, from savagery to civic organisation, from egoism to altruism”. William John McGee – the president of the newly formed American Anthropological Association, who had been hired to head the fair’s ethnology department – issued a call for African “pygmies”, who were believed to represent the lowest rung on the evolutionary scale.

Verner wrote to McGee to offer his services. Four years earlier, Verner had brought a large collection of ethnological material to the Smithsonian Museum – as well as two boys from the “Batetela cannibal tribe”, whom Verner had taken from Congo and offered to the museum as models. (Neither ever returned home.) Since then, Verner told McGee, he had written extensively on scientific matters in Africa, noting his articles on “pygmies” published in the Spectator and the Atlantic Monthly. Verner added that he was a personal friend of the Belgian king, Leopold II, who controlled Congo Free State, and had promised any assistance required in the “diplomatic mission”.

In a deal finalised in October 1903, Verner was commissioned as a “special agent” by the Louisiana Purchase Exposition Company, charged with conducting an expedition into the African interior to obtain anthropological material and offer “certain natives the opportunity of attending the Exposition in person”. The exacting list called for the retrieval from Congo of “one pygmy patriarch or chief. One adult woman, preferably his wife. Two infants, of women in the expedition,” and “four more pygmies, preferably adult but young, but including a priestess and a priest, or medicine doctors, preferably old.”

McGee stipulated that Verner must secure the voluntary attendance of the delegation and return them safely to their homes and obtain all permissions and the support of King Leopold II. A total of $8,500 was allocated, including $500 for Verner’s compensation and an additional $1,500 set aside for unforeseen contingencies. Verner proposed taking a navy warship or gunboat to Congo to “greatly lighten enferences” – a proposition that apparently failed to alarm the fair’s officials. Instead, he received official letters of recommendation signed by McGee as president of the American Anthropological Association and acting president of the National Geographic Society. For good measure, Verner secured a letter addressed to Leopold from John Hay, the US secretary of state.

In late November 1903, Special Agent Verner set sail from New York harbour. By early December, he had arrived in London – just as the British consul Roger Casement was returning to the city to file his report investigating atrocities against Congo natives. Verner had stopped to outfit himself with tropical and hunting equipment: he would ship at least 80 cases of supplies – including rifles and ammunition – to Congo.

En route to Africa, Verner wrote to McGee to announce that King Leopold was “so much interested” that he would attend the fair himself, and assured McGee that the cooperation of the so-called pygmies was even more likely now that he had acquired “a more considerable equipment than I at first contemplated,” an apparent reference to the military supplies he had purchased in London. Verner reiterated that he had, in a previous letter to McGee, “covered the ground of what I thought wise in the event of a non-assent of the pygmies”; however, that letter has not been located.

McGee replied: “As you are now placed, you are a law unto yourself and I have implicit confidence in the competence of the court.” The letter implicitly sanctioned whatever was necessary for Verner to do to carry out his mission.

A week later, Verner reported his first triumph. “The first pygmy has been secured!” he exclaimed on March 20 1904, the day Ota Benga’s life would radically change. Verner told McGee that Ota Benga was obtained from a village where he had been held captive, at a remote site in the forest “twelve days march from any white settlement”. And while it is possible that Verner went alone into a remote location in search of his prey, the area, Bassongo, was the site of a well-known slave market and government post where human trafficking was pervasive.

Later, retelling the tale of Benga’s capture in a Harper’s Weekly article, Verner said that when he found Benga, he was held captive by the Bashilele, who he claimed were cannibals. “He was delighted to come with us,” wrote Verner, “for he was many miles from his people, and the Bashilele were not easy masters.”

However, he told the Columbus Dispatch that he was waiting for a ship to come in when he ventured a short distance and spotted Ota Benga, along with a few members of his tribe. In this contradictory retelling, he said he made arrangements with a chief to take Benga with him. “He was willing and even anxious to go with me, for the memory of his awful escape from the hungry cannibals had not been forgotten by him.”

However, he told the Columbus Dispatch that he was waiting for a ship to come in when he ventured a short distance and spotted Ota Benga, along with a few members of his tribe. In this contradictory retelling, he said he made arrangements with a chief to take Benga with him. “He was willing and even anxious to go with me, for the memory of his awful escape from the hungry cannibals had not been forgotten by him.”

In yet another account, he wrote that Benga had been captured in war by enemies of his tribe who were in turn defeated by government troops, who then held Benga. Benga elected to travel with Verner on learning that he “wanted to employ pygmies”.

The circumstances of their encounter would continue to change in the telling over the years. The only consistent themes were the alleged threat of cannibals and Verner’s role as Benga’s saviour. But even without knowing the specific details of their meeting, we can safely assume that Benga was hunted down by Verner.

The British consul Roger Casement’s recent inquiry in Congo had confirmed many earlier reports of mass atrocities under Leopold’s rule, including widespread enslavement, murder, and mutilation. Men came to Casement with missing hands, as the African American missionary William Sheppard and others had previously documented. Some claimed that they had been castrated or otherwise mutilated by government soldiers and sometimes by white state officials. The widespread and wanton practice of mutilation “is amply proved by the Kodak”, said Casement who submitted photographs of at least two dozen mutilated victims. Most observers during this period noted the common sight of Congolese chained by their necks and forced to work for the state. While Benga’s personal experience in Congo was not recorded, the incursions deeper into the forest for rubber and ivory would, for his forest-dwelling people, mean greater exposure and vulnerability to state abuses.

Casement’s report was submitted to the British crown around the time Benga and Verner met. The report brought overnight fame to Casement, and international scrutiny to Leopold, who set up a commission comprising a Swiss jurist, a Belgian appellate judge, and a Belgian baron, to investigate the allegations. But none of the revelations would spare Benga who was now securely in Verner’s net. After obtaining Benga, Verner advised McGee to send a statement to the prominent daily, weekly, and monthly publications to spread the news of his expedition.

On 21 March, Verner wrote to McGee to report that he, accompanied by a state official “of eminence and responsibility”, had descended on a village. They obtained another “pygmy” who had been temporarily placed in a local mission.

McGee praised Verner’s efforts. “The more I have reflected on the distances and other difficulties you have had to overcome, the more have I been impressed with the clearness of your foresight and the soundness of your plans,” he wrote.

McGee reported that plans for the fair were proceeding well. The University of Chicago’s Professor Frederick Starr had arrived with nine indigenous Ainu people from Japan. The Patagonians were on a boat from Liverpool, and 300 natives “including Igorottes and Negrito pygmies” had arrived the preceding Monday. Four hundred more were en route from San Francisco. But the African “pygmies” – a term once associated with monkeys – were to be the signal attraction, and with the fair a month away and Verner a month behind his deadline, McGee cared only that Verner complete his mission successfully. “I make but a single plea,” McGee wrote, “get the Pygmies.” To that Verner responded: “We are not going to fail unless death comes.”

In April, Verner wrote to McGee to report hostilities between state troops and the Congolese people that had compounded the difficulties he was having persuading any forest dwellers to return with him. Verner later recalled that the old men shook their heads gravely, the women howled through the night, and the medicine men “violently opposed” his scheme to take some of their people to America. Yet Verner claims he changed their minds by simply supplying salt – which traders and company officials paid the Congolese for their goods and which Verner claimed was more valuable than gold. Somehow, the armed and determined Verner won over a boy he called Malengu, then another called Lanunu, then Shumbu and Bomushubba. He later said more than 20 males in all promised to accompany him, but more than half of them “subsequently gave way to their fears”. Most of the “Batwa” ran away “but we succeeded in keeping some to their promise.”

On the morning of 11 May, Verner, accompanied by Ota Benga and a band of eight other young males of undetermined ages, boarded a steamer for the long journey down the Kasai River to Leopoldville and the mouth of the Congo. The delegation arrived in New Orleans on 25 June. According to the ship’s passenger list, the youngest boy, Bomushubba, was only 12, followed by Lumbaugu, who was said to be 14. “Otabenga” – the name Verner used privately with Benga – was said to be 17 – significantly younger than Verner would later claim.

Although the delegation had arrived nearly two months late and fell far short of the goal – not one woman, infant, or elderly medicine man was among them – Verner’s African visitors were giddily greeted in St Louis.

“African Pygmies for the World’s Fair” was the headline in the St Louis Post-Dispatch on 26 June. Soon, the newspapers would mock the exhibited Africans with one offensive headline after another: “Pygmies Demand a Monkey Diet: Gentlemen from South Africa at the Fair Likely to Prove Troublesome in Matter of Food” and “Pygmies Scorn Cash; Demand Watermelons”.

Verner himself did not arrive in St Louis with his coveted acquisitions. Instead, he disembarked in New Orleans on a stretcher and was transported to a sanatorium. Some people suspected sunstroke. Casement, who happened to be on the same ship heading to America, observed that many thought Verner was “cracked”.

McGee dispatched someone to escort Benga and Verner’s other captured “pygmies” from New Orleans to St Louis. A short time later, Verner was back on the scene, writing articles about his adventures in Congo. In one account, beneath the headline: “An Untold Chapter of My Adventures While Hunting Pygmies in Africa,” a large portrait of a triumphant Verner, wearing a suit and bow tie, appears alongside pictures of his captives, including Benga, whom he claimed to have obtained for $5 worth of goods.

In another published in the St. Louis Post Dispatch, he claimed Ota Benga was a cannibal – “the only genuine cannibal in America today”. On the fairgrounds the delegation was pinched, prodded and poked while their pet parrots and monkeys were taunted and burned with cigars. As the temperatures dropped, they were also subjected to the frigid fairgrounds without adequate clothing or shelter. Behind the scenes, they were measured, photographed and plaster casts were taken for busts.

Now, two years later, having been deposited by Verner in New York, Benga was once again subjected to the raucous clamour of spectators and a callous disregard for his humanity. Hornaday, ever the showman, eagerly fielded requests for photographs and interviews from around the US and the world.

On Thursday 13 September, the New York Times published a letter written by one Dr MS Gabriel, who said he had seen Benga at the zoo and found the objections to the exhibit “absurd”. While the ministers protested about Benga’s presence in a cage, it was, on the contrary, “a vast room, a sort of balcony in the open air”, which allowed visitors to observe the African guest “while breathing the fresh air”.

Benga’s childlike ways and broken English were pleasing, Gabriel continued, “and the visitors find him the best of good fellows”. It was a pity, he said, that Hornaday did not give lectures related to such exhibits. “This would emphasise the scientific character of the service, enhance immeasurably the usefulness of the Zoological Park to our public in general, and help our clergymen to familiarise themselves with the scientific point of view so absolutely foreign to many of them.”

Hornaday saved the clippings and proudly shared them with his friend, the paleontologist Osborn.

“The enclosed clippings are excellent,” Osborn replied. “Benga is certainly making his way successfully as a sensation.”

By Sunday 16 September, a week after his debut, Benga was no longer in the cage, but roamed the park under the watchful eye of park rangers. That day a record 40,000 people visited the zoo. Wherever Benga went, hordes followed in hot pursuit. The rowdy crowd chased Benga, and when he was cornered, some people poked him in the ribs or tripped him, while others merely laughed at the sight of a frightened “pygmy”. In self-defence, Benga struck several visitors, and it took three men to get him back to the monkey house.

Hornaday wrote to Verner on Monday 17 September, to complain. “I regret to say that Ota Benga has become quite unmanageable,” he said. “He has been so fully exploited in the newspapers, and so much in the public eye, it is quite inadvisable for us to punish him; for should we do so, we would immediately be accused of cruelty, coercion, etc., etc. I am sure you will appreciate this point.”

Hornaday complained that “the boy does quite as he pleases, and it is utterly impossible to control him”. He expressed dismay that Benga threatened to bite the keepers whenever they tried to bring him back to the monkey house.Hornaday’s star attraction was turning into a liability. “I see no way out of the dilemma,” he wrote, “but for him to be taken away.”

That Friday, a crowd invaded the park and pursued Benga as he walked through the woods. Across the country, newspaper headlines revelled in Benga’s plight. The Chicago Tribune joined the banter under the headline: “Tiny Savage Sees New York; Sneers”. Three thousand miles away, the Los Angeles Times covered the sensation on Sunday 23 September, under the headline: “Genuine Pigymy Is Ota Banga: Can Talk with Orangoutang in New York.”

Another self-described “African explorer”, John F Vane-Tempest, published an article in the New York Times, disputing the zoo’s classification of Benga as a “pygmy”. Under the headline “What Is Ota Benga?” Vane-Tempest said that on the basis of his experience, Benga was actually a southern African Hottentot, and claimed to have conducted a conversation with Benga “in the tongue of the Hottentots”. According to Vane-Tempest, Benga had professed great satisfaction with his captivity. “He liked the white man’s country, where he was treated as a King, had a cozy room, a splendid room in a palace full of monkeys, and enjoyed all the comforts of home except a few wives.” This preposterous account was nevertheless presented as a straightforward news story.

Another self-described “African explorer”, John F Vane-Tempest, published an article in the New York Times, disputing the zoo’s classification of Benga as a “pygmy”. Under the headline “What Is Ota Benga?” Vane-Tempest said that on the basis of his experience, Benga was actually a southern African Hottentot, and claimed to have conducted a conversation with Benga “in the tongue of the Hottentots”. According to Vane-Tempest, Benga had professed great satisfaction with his captivity. “He liked the white man’s country, where he was treated as a King, had a cozy room, a splendid room in a palace full of monkeys, and enjoyed all the comforts of home except a few wives.” This preposterous account was nevertheless presented as a straightforward news story.

In this midst of this free-for-all, Reverend Matthew Gilbert, of Mount Olivet Baptist Church, wrote to the New York Times to report that the spectacle of Benga’s captivity had ignited the outrage of African-Americans across the US. “Only prejudice against the negro race made such a thing possible in this country,” Gilbert said. “I have had occasion to travel abroad, and I am confident that such a thing would not have been tolerated a day in any other civilised country.”

He enclosed a sober statement from a committee of the Ministers’ Union of Charlotte, North Carolina, that read: “We regard the actors or authorities in this most reprehensible conduct as offering an unpardonable insult to humanity, and especially to the religion of our Lord Jesus Christ.”

But others were not so sure. The Minneapolis Journal published a photograph of Benga holding a monkey, and claimed, “He is about as near an approach to the missing link as any human species yet found.”

On 26 September, with protests mounting, the city controller’s office sent an official to investigate a report that the zookeepers were accepting payments to permit visitors to enter Benga’s sleeping quarters. The unnamed inspector visited Benga, whom he found clad in a khaki suit and a soft gray cap. He noted Benga’s “boyish appearance” and described him as an African native who park visitors believed was “some sort of a wild man who can understand monkey talk.” He concluded: “Without attempting to discuss the intellectual accomplishments or demerits of the gentleman, it may be stated that to the unscientific mind this native of Darkest Africa does not materially differ in outward appearance at least from some of the natives of darkest New York.” He also was sceptical about claims that Benga’s intellect was stunted and that he could understand the chattering monkeys. He said that he would be more convinced of Benga’s arrested development if Benga did not speak some English, and said that if Benga could understand the monkeys, “he kept the secret well to himself.”

The tide had begun to turn against Hornaday and the zoo. Heated objections had begun to appear even in the pages of the New York Times. Even worse, Benga was now mounting increased resistance. When handlers tried to return him to the cage, he would bite, kick and fight his way free. On at least one occasion he threatened caretakers with a knife he had somehow got hold of. Hornaday was also unsettled by the unruly mobs that chased and taunted Ota Benga. Exasperated, Hornaday attempted to reach Verner, who had inexplicably left the city. “The boy must either leave here immediately or be confined, Hornaday said in a letter to Verner. “Without you, he is a very unruly savage.”

But as much as much as he wished to unload Benga, Hornaday refused to release him to Gordon’s orphanage unless Gordon promised to return him to Verner upon his return to New York. Gordon would not agree.

In the meantime, controversy swirled around the zoo as protests picked up steam around the country. Even white southerners leapt at the opportunity to mock New Yorkers for the unseemly display – “A Northern Outrage,” in the words of one Louisiana newspaper, which added: “Yes, in the sacred city of New York where almost daily mobs find exciting sport in chasing negroes through the streets without much being said about it.”

Finally, on the afternoon of Friday 28 September, 20 days after he first went on display – Benga quietly left the zoo, escorted by the man who had captured him. His departure would be as calm and contained as his debut was frenetic and flamboyant. Apparently no reporters were alerted to witness Benga’s farewell. He was taken to the Howard Coloured Orphan Asylum, in Brooklyn’s Weeksville neighbourhood – the finely appointed orphanage run by Gordon, in the city’s largest and most affluent African-American community.

“He looks like a rather dwarfed colored boy of unusual amiability and curiosity,” Gordon said. “Now our plan is this: We are going to treat him as a visitor. We have given him a room to himself, where he can smoke if he chooses.” Gordon said Benga had already learned a surprising number of English words and would soon be able to express himself.

“This,” he asserted, “will be the beginning of his education.”

In January 1910, Ota Benga was sent to Lynchburg, Virginia – a city of nearly 30,000 people, with electric streetcars, sumptuous mansions, sycamore trees and soaring hills. As Gordon had promised when Benga first came into his care, he was sent to the Lynchburg Theological Seminary and College, a school noted for its all-black faculty and staff, which prided itself on its fierce autonomy from the white American Baptist Home Mission. At the time, many white patrons of black education insisted that blacks only receive an industrial education, but Lynchburg Theological continued to offer its students liberal arts courses.

Benga lived in a rambling yellow house across the road from the school with Mary Hayes Allen, the widow of the former president of the seminary, and her seven children. Benga, usually barefoot, often led a band of neighborhood boys to the forest to teach them the ways of a hunter: how to make bows from vines, hunt wild turkeys and squirrels, and trap small animals. In his scrappy English, Benga often regaled the boys with stories of his adventures hunting elephants – “Big, big”, he would say, with outstretched arms – and recounted how he celebrated a kill with a triumphant hunting song.

In Benga they found an open and patient teacher, and a companion who uninhibitedly relived memories of a lost and longed-for life. Benga, in turn, had found a surrogate home and family, and would learn their customs and the contours of their binding blackness. In their sermons and spirituals, he surely recognised a familiar sorrow.

Still, they did not know the piercing rupture of captivity – the eternity of alienation that many of their forebears had known, which Benga himself now knew. While they were burdened and disdained in America, it was the land they had tilled and spilled blood on, the land where they created life and buried their dead. For all the rejection, they were home.

Benga had only memories, and no one but he could know what form they took. Was his sleep troubled by nightmares of being stalked by mobs, or being caged? Was he haunted by visions of murdered loved ones, or of starving, tortured, and chained Congolese?

Some nights, beneath a star-speckled sky, the boys recalled, they would watch Benga build a fire, and dance and sing around it. They were enraptured as he circled the flames, hopping and singing as if they were not there. They were no older than 10, too young to grasp the poignancy of the ancient ritual.

But as he, and they, grew older, something changed. By 1916, Benga had lost interest in their excursions to hunt and fish, and no longer seemed so eager a friend to the neighbourhood children. Many had noticed his darkening disposition, his all-consuming longing to go home. For hours he would sit alone in silence under a tree. Some of his young companions would recall, decades later, a song he used to sing, which he had learned at the Theological Seminary: “I believe I’ll go home / Lordy, won’t you help me.”

In the late afternoon of 19 March 1916, the boys watched as Benga gathered wood to build a fire in the field. As the fire rose to a brilliant flame, Benga danced around it while chanting and moaning. The boys had seen his ritual before, but this time they detected a profound sorrow: he seemed eerily distant, as vacant as a ghost.

That night, as they slept, Ota Benga stole into a battered grey shed across the road from his home. Before daybreak, he picked up a gun that he had hidden there, and fired a single bullet through his own heart.

In the harrowing stillness, he was free (source).

Photo credit: 1) A portrait of Ota Benga taken in Congo. His sharp teeth were the result of tooth chipping, a practice that was popular among young men. Photograph: American Museum of Natural History. 2) The New York Times report about Ota Benga on 9 September, 1906. Photograph: The New York Times. 3) Ota Benga (second from left) and fellow countrymen at the St Louis World’s Fair, 1904 Photograph: University of South Carolina. 4) Reverend James Gordon led the protests against Ota Benga’s exhibition and captivity in the monkey house. Photograph: Anne Spencer House and Garden Museum. 5) Samuel P Verner took Benga captive in Congo and brought him back to the United States. Photograph: University of South Carolina. 6) Samuel P Verner with two boys from the Batetela tribe in Congo in 1902 Photograph: Doubleday. 7) William Temple Hornaday, the zoologist and founding director of Bronx Zoo, where Ota Benga was exhibited. Photograph: Wildlife Conservation Society.

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact

What a sad story. Such abominable treatment of this young man! Oh the horrors of the treatment that our people of color (African Americans and Native Americans) have had to endure. People matter — all people matter! We are God’s creation — not man’s.