An early reader of this portrait of Samuel Jesse Battle harkened back to the Old Testament, verse three of Psalm 106: “Blessed are they who observe justice, who do righteousness at all times!”

An early reader of this portrait of Samuel Jesse Battle harkened back to the Old Testament, verse three of Psalm 106: “Blessed are they who observe justice, who do righteousness at all times!”

The connection was fitting. Battle’s enormous courage, seemingly limitless charity, and unfailing insistence on dignity far exceeded his human flaws. He would not be told no when no was unjust. Expecting equal treatment — and occasionally paying dearly for his good faith — he persevered to prevail over some of New York’s most closely guarded racial barriers.

The moral bearing that propelled Battle’s victories shines most vividly through his own words. In 1949, he hired Langston Hughes to write his autobiography, spent hours speaking with the renowned Harlem Renaissance poet, and provided him with handwritten recollections. The result was a never-published, eighty-thousand-word book titled “Battle of Harlem.” One copy of the manuscript resides among Hughes’s papers at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Battle’s grandson Tony Cherot has custody of a second copy. The two are not identical. After publishers showed no interest, Battle worked with a new partner in hope of making the book more marketable. He also secured a foreword by former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

All to no avail.

Relying on Cherot’s copy of the revised manuscript, I set out to bring Battle to life in contexts that stretched from the post-Civil War South through turn-of-the-century New York, through his fight to join the New York Police Department, through the Roaring Twenties and Prohibition, through the glorious rise and tragic fall of Harlem, through the Great Depression and two world wars. From his rambunctious boyhood in 1880s rural North Carolina to his death in Harlem in 1966, Battle was so engaged in his times that his journey illuminates the sagas of the United States and its largest city as oppressively experienced by African American citizens.

To the extent that I have succeeded in capturing the man and his eras, I owe a debt of gratitude to scholars and authors who documented the country’s social, cultural, political, economic, sporting, and military evolutions. As but two examples, Gilbert Osofsky’s “Harlem: The Making of a Ghetto” was invaluable to understanding how the forces of racial hatred and money shaped the capital of black America, while Jervis Anderson’s “This Was Harlem” tells of the people who, against all odds, built a vibrant society there. True to form, the New York Public Library and its Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture came through as repositories of documents, histories, biographies, journals, and out-of-print memoirs that bolstered Battle’s reminiscences. Then there was the New York Age, whose crusading zeal and depth of coverage place the weekly in the ranks of America’s finest newspapers. Although little remembered even in New York, the Age’s seven decades of journalism are foundational to understanding black America from the end of the nineteenth century to the middle of the twentieth.

Arnold Rampersad’s monumental two-volume “The Life of Langston Hughes” indispensably illuminated the man, the artist, and his times. Similarly, Cherot’s boyhood memories serve as the basis for descriptions of Battle’s life in retirement, including his relationship with Hughes.

Battle’s own words remain the heart of the matter. They are the wellspring of countless facts, because he turned out to have possessed an astonishingly good memory. As captured by Hughes, his voice breathes personal vitality into passages ranging from brief quotations to sections several hundred words long. I have drawn the vast majority of these materials from the revised Battle of Harlem manuscript (editing lightly for sense or brevity) and present them without endnote references.

Battle memorialized his life in two additional places: in a 1960 interview with Columbia University’s Oral History Collection and in the written notes he prepared for Hughes. I marked excerpts of these with references to endnotes.

Words left behind by the remarkable Wesley Augustus Williams are similarly treated. Inspired by Battle, Williams waged the struggle to integrate the New York City Fire Department. In retirement, he recounted his experiences in numerous speeches and in an extended interview given to the author of a master’s thesis. Typescripts of the speeches and the thesis reside at the Schomburg Center and are the collective basis for a narrative that intertwines with Battle’s.

Reared to be a God-fearing Christian, Battle lived by a simple moral code. He applied the Golden Rule to others and demanded it in return, with equally unflagging bravery and optimism, even under the hardest circumstances. This is one more way of expressing the thought called from the psalm by my early reader, my friend, the estimable Vince Cosgrove. For Battle was indeed a man who observed justice and who demonstrated the power that can beat in the heart of one righteous man.

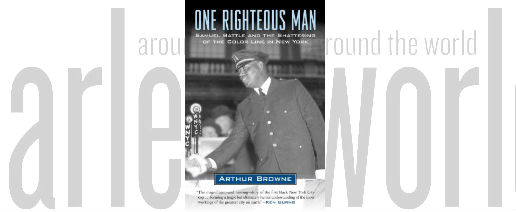

Excerpted from “One Righteous Man: Samuel Battle and the Shattering of the Color Line in New York” by Arthur Browne (Beacon Press, 2015). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact