When Rebecca Hodges sent her son to Pre-K in Brooklyn, she was excited for the year to come—full of learning adventures and making new friends. While his education got off to a strong start, Hodges quickly realized something was wrong.

When Rebecca Hodges sent her son to Pre-K in Brooklyn, she was excited for the year to come—full of learning adventures and making new friends. While his education got off to a strong start, Hodges quickly realized something was wrong.

Her son, just five years old, was gaining an alarming amount of weight. Within 6 months, he had gained 11 pounds and his body mass index went from the 60th to the 98th percentile. He began having trouble breathing and sleeping at night. “His diet at home, which was low in sugar, did not change,” she said. “When I brought him to the pediatrician and we started asking him questions about what he was drinking and eating, we realized this was happening because of school.”

Hodges discovered her son was drinking two boxes of chocolate milk a day, each with 20 grams of total sugar, 12 grams of natural sugar from lactose and 8 grams of added sugar. Those 8 grams of added sugar add up to almost one-third of a child’s daily sugar allowance according to the American Heart Association and the World Health Organization, which both recommend that children limit sugar to 5 percent of their daily intake —about 6 teaspoons or 25 grams — of added sugar per day.

Hodges’s son is far from a unicorn in the classroom. He is just one of the thousands of children growing sick from sugar in a country where the obesity epidemic has reached epic rates and shows no signs of slowing down. Health-care costs related to obesity in this country topped $1.72 trillion dollars in 2018.

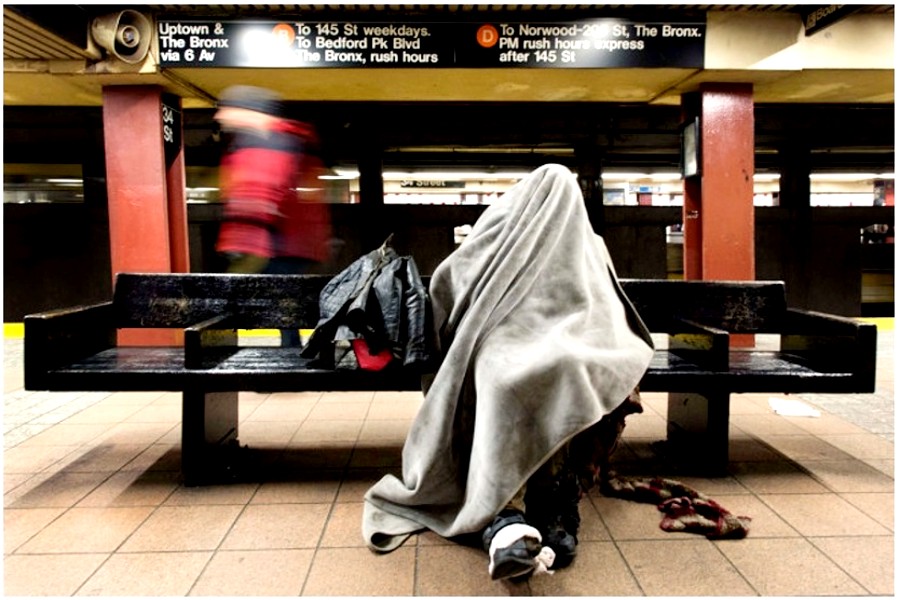

In the state of New York, childhood obesity has tripled over the past three decades. In New York City, 40 percent of NYC public school students aged 6 to 12 are overweight or obese. While NYC’s overweight and obesity numbers have been relatively constant over the last 5 years, in communities with underserved populations obesity is on the rise.

Childhood obesity disproportionately affects low-income communities and communities of color. In New York City, children living in the Bronx have the highest prevalence of overweight (43 percent vs. 4 percent in Brooklyn, 40 percent in Staten Island, 39 percent in Queens, 38 percent in Manhattan).

Thirty-five percent of East and Central Harlem students in grades 9-12 are overweight and obese compared to 28 percent in NYC.

According to the Youth Risk Behavior Survey by the CDC, compared to New York City students, a higher proportion of East and Central Harlem students are overweight and obese. Thirty-five percent of East and Central Harlem students in grades 9-12 are overweight and obese compared to 28 percent in NYC. Obesity rates in low income East Harlem are higher than what they are on the wealthier Upper East Side, just a few short blocks away.

…according to research reported in Obesity Reviews, obese children and adolescents were approximate “five times more likely to be obese in adulthood than those who were not obese.”

Additionally, according to research reported in Obesity Reviews, obese children and adolescents were approximate “five times more likely to be obese in adulthood than those who were not obese.”

Research also suggests that consuming sweetened beverages such as chocolate milk every day can train a child’s palate to prefer sugar-sweetened foods.

In response, more and more school districts have been removing chocolate milk from their menus. Chocolate milk is banned in Boulder, Minneapolis, Washington D.C., Montgomery County, Maryland, and most recently, San Francisco.

Even New York City’s Department of Corrections (DOC) has phased out sugar-sweetened beverages because of their ties to costly obesity-related diseases. Ten years ago DOC Commissioner Martin Horn told Gothamist, “the move will save money in the long run because healthier inmates will be less prone to strokes, heart attacks or diabetic shock on the city’s watch.” Today, the DOC bans both chocolate milk and juice. And yet, NYC’s Department of Education (DOE) continues to serve chocolate milk (and juice) to 1.1 million children a day.

Rumors have been circulating that DOE may remove chocolate milk from public schools, but it’s deputy press secretary Avery Cohen, would not confirm. She offered this statement: “Our priority is the health and well-being of our students, and every day, we offer a variety of healthy food options that exceed USDA standards. We’ll continue to work with the Department of Education and Department of Health to ensure our meals are nutritious.”

Instead of eliminating chocolate milk as a public health policy, the DOE has outsourced chocolate milk decisions to principals, who may choose to stop serving it in their individual schools. This shifts a huge burden to educators, who want to keep peace with parents of differing views, and who are presumably not health professionals.

Rather than principals, matters of health and nutrition are the purview of the city’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH), which, interestingly, forbids chocolate milk in day-care centers and camps, which are directly under its control.

But the DOHMH does not direct DOE policy and, therefore, cannot control what it serves. Still, the correlation between poverty and obesity has led the DOHMH to create the Center for Health Equity (CHE), which “works to ensure that every New Yorker, regardless of where they live, has the opportunity to lead their healthiest lives.” CHE actually directs a task force of employees who work in zip codes where childhood obesity is highest—East and Central Harlem, North and Central Brooklyn and the South Bronx— to encourage the removal of chocolate milk from public schools.

CHE’s teams offers a “Healthy Schools Toolkit,” which includes a variety of messaging tools to encourage schools to stop serving chocolate milk including “Choose Plain Milk” posters that contain helpful facts such as “elementary school children are already used to drinking plain milk, because all licensed NYC group child-care centers and Head Start programs are required to serve only plain, low-fat milk to children 2 years and older!”

CHE also offers stickers, postcards, and form letters for parents to request that chocolate milk be removed from the cafeterias. The letters read, “Our school would like to stop serving chocolate milk in the cafeteria to promote healthy eating and reduce students’ consumption of sugary beverages. For the two milk options that are required by the USDA, we would like to offer our students plain (unflavored) 1 percent milk and skim milk.”

It may seem odd that one agency within New York City’s government is putting into schools exactly what another agency is trying to remove from schools, but that is precisely what’s happening. The dairy lobby may be the reason why.

The American Dairy Association has significant skin in this game; DOE spent $18.3 million on milk and yogurt in FY 2018. (Requests made for the amount DOE spent on chocolate milk were not answered for this story and the Freedom of Information Act request has not yet been answered.) The American Dairy Association also finances many important Office of Food and Nutrition Services (OFNS) programs, including working to increase breakfast after the bell, after-school meals, summer meals and healthier meals all around; this summer it paid for part of the DOEs promotional food truck. It is not hard to see why the DOE might not want to alienate such a benefactor.

The dairy lobby continues to advocate against the removal of sweetened milk, arguing that its removal might cause a nutrient deficit—chocolate milk contains 8 grams of protein, 25 percent vitamin D, and 30 percent calcium— or deter children from drinking milk altogether.

But a decrease in plain milk consumption is far from a certainty. While there may be some initial drop in plain milk consumption when chocolate milk is removed, a University of Connecticut Rudd Center study found that acceptance of plain milk increases significantly two years after flavored milk is removed from school cafeterias.

More recently, officials in San Francisco tested the removal of chocolate milk in five schools to determine whether or not it would not deter plain milk consumption. They found no decrease in the number of milk cartons kids put on their trays in two schools, and only a slight dip in the other three. The policy has become a success.

Betti Wiggins, the officer of nutrition services for the Houston Independent School District and a school food hero for the work she did in Detroit, sees the dairy industry as an inappropriate influence. “The main thing I’ve been trying to do here in Houston is take chocolate milk off my menu, and it is like climbing Mount Everest because of the impact of the dairy lobby,” she said in a roundtable discussion on Civil Eats. “In Michigan [which she left in 2017], I did not serve chocolate milk. Now, not even three years later, chocolate milk is back on the menu. So, we need to look at the influence of the industry: Are they truly working in the best interest of our children?”

The medical community is unpersuaded by the argument that the nutritional benefits of drinking flavored milk outweigh the risk factors associated with its high sugar content.

Dr. Ileana Vargas, an Assistant Professor of Pediatric Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism at Columbia University Medical Center, says chocolate milk presents health risks for all children. “There are dental issues, issues of excess body weight and risks for type 2 diabetes and fatty liver disease in children,” she says. “Yes I understand that it does contain nutrients that your body needs, but so does plain milk.”

Indeed, plain milk and other dairy products are excellent sources of calcium. There are also many non-dairy sources of calcium present in foods served during school lunch—dark green vegetables such as kale, spinach, collard greens, and broccoli. Many foods are also prepared or fortified with calcium, including tofu, non-dairy milks like soy and almond milk, bread, tortillas, and breakfast cereals.

“There is no nutritional reason to serve flavored milk to kids,” says Dr. Tamara Hannon, a member of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and a pediatric endocrinologist who has practiced at Riley Hospital for Children in Indianapolis for 20 years. “The added sugar just adds to total daily intake of sugar that kids have, which contributes to the obesity epidemic.”

Dr. Hannon says that the chocolate milk controversy is fueled not by what is best for children, but what puts the most money in the pockets of special interests. “The dairy lobby is very much in favor of all milk products in schools,” she says. “But looking at science, you see that what is causing obesity is low-fat sugar-sweetened drinks like flavored milk.”

Politicians are also growing tired of seeing children get sick from what they see as government-sponsored sugar consumption. Brooklyn Borough President Eric L. Adams is dedicating himself to fighting the health crisis and improving school food. He has already successfully banned processed meats from public schools and would like to see chocolate milk go too. “We should not be serving sugar-sweetened beverages in schools at all,” he says. “We should prioritize water. Our kids’ health depends on it.”

What about water? Turns out kids should be drinking a lot more of it. Studies have shown that access to fresh drinking water is critical: it can lead to improved weight status, reduced dental issues, and improved cognition among children and adolescents.

It’s a beverage many parents are getting behind. Donna Perry, the founder and CEO of the Courageously Curvy Girls Foundation, has two daughters who both gained weight in their first years of public school. She attributes their weight-gain to a combination of chocolate milk and insufficient physical activity.

To help children maintain healthy habits, she is adamant that the DOE stop serving chocolate milk in schools. “What you choose to serve your children in your home is up to you, but we should not have the government feeding this health crisis,” she says. “We would do better with water, which is healthier and cheaper on the front end and in terms of health costs of obesity.”

Water fountains in public schools are notoriously clogged or out of service, so the DOE has installed cafeteria water jets — electrically cooled, large, clear jugs with a push lever for fast dispensing — where parents have requested them, but, as of 2016, only 55 percent of schools had them.

Water jets have been shown to be an important tool in fighting obesity. According to a study published in JAMA Pediatrics that was conducted in New York City’s public elementary and middle schools, installing water jets in cafeterias was associated with a small but significant average weight loss among students. “Water jets could be an important part of the toolkit for obesity reduction techniques at the school setting,” the study’s authors concluded.

Rather than funding water jets (about $700 each) in all schools, DOE continues to purchase chocolate milk.

Rather than funding water jets (about $700 each) in all schools, DOE continues to purchase chocolate milk reports via source.

“When you look at chocolate milk on a national scale, you see that 70 to 80 percent of all flavored milk in this country is served in schools, which means parents do not opt to serve it at home,” says chef Ann Cooper, whose Boulder Valley School District stopped serving chocolate milk in 2009. “So why should we serve it in schools when they don’t serve it at home? This is all about the dairy lobby. There is no justification for it at all.”

Andrea Strong is a journalist who covers the intersection of food, policy, business and law. She is also the founder of the NYC Healthy School Food Alliance.

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact