“… home to such African-American luminaries as composer Duke Ellington, Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall and civil rights activist W.E.B. DuBois.”

Hundreds of New York City’s most glorious brownstones and majestic townhouses will be protected from developers and preserved for generations under a major rezoning proposed for West Harlem.

The plan would safeguard an architectural treasure trove by imposing height limits in the neighborhood for the first time ever, radically transforming the zoning of a 90-block area.

If the sweeping proposal from the Department of City Planning is approved, it will mark the first time the neighborhood’s zoning has been updated since 1961 — when Robert Wagner was mayor and Nelson Rockefeller was governor.

The so-called downzoning will preserve roughly 95% of the 1,900 lots bounded by W. 126th St. on the south; W. 155th St. to the north; Riverside Drive on the west, and Convent and Edgecombe Aves. to the east.

That includes Sugar Hill, the affluent historic district named for the sweet life enjoyed by its residents, and Hamilton Heights, traditional home to such African-American luminaries as composer Duke Ellington, Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall and civil rights activist W.E.B. DuBois.

“This is huge!” says Manhattan Borough President and mayoral hopeful Scott Stringer.

“By limiting both height and density, it removes the incentive to demolish small buildings and townhouses and replace them with towers — and that keeps gentrification at bay.”

The rezoning will protect West Harlem’s low-lying scale and “guide future development” to mesh with the area’s prewar apartment houses and Beaux Arts, Queen Anne and Romanesque Revival brownstones, says City Planning Commissioner Amanda Burden.

“If my house blows up today, a developer under current zoning could replace the four-story brownstone with a 10- or 15-story building tomorrow,” said Pat Jones, co-chair of Community Board 9’s land use committee. “That out-of-scale development will no longer be possible.”

Heights would be capped at four to six stories on almost all crosstown, residential mid-blocks. They could rise only to six to eight floors on St. Nicholas and Amsterdam Aves. and up to 12 stories on Broadway, a review of the plan shows.

The impetus for the downzoning: Columbia University’s upzoning of an adjacent, 17-acre parcel in Manhattanville, where it will erect a $6 billion, 16-building super-campus, north of 125th St. and west of Broadway, over the next 25 years.

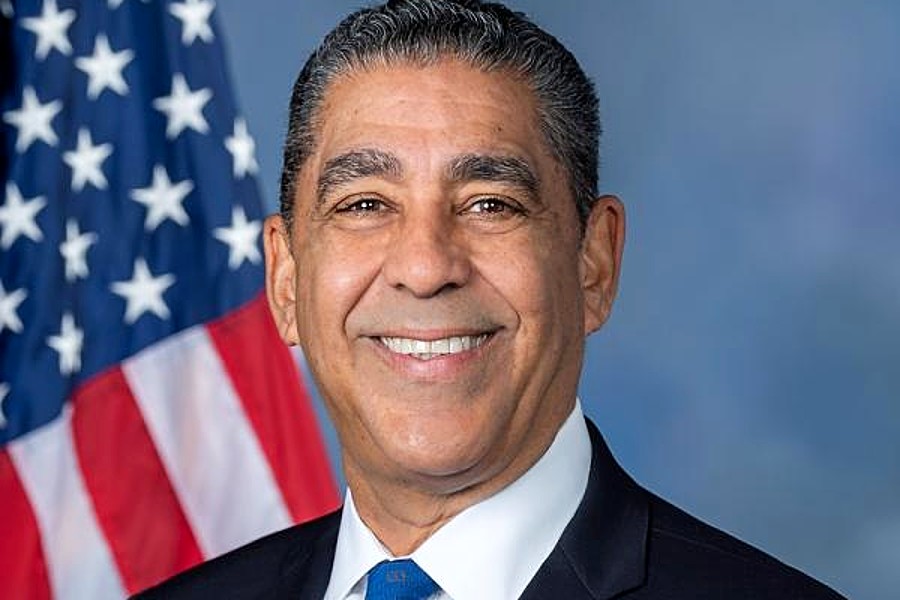

Stringer and City Councilman Robert Jackson, who represents the area, had pressed City Planning officials to rezone the adjoining swath so West Harlem could co-exist with Columbia — and not be dominated by it.

“Columbia is humongous, its endowment is in the billions, and people have a real fear that housing costs will go up and they’ll no longer be able to afford their homes because the new campus will fuel gentrification,” Jackson says.

“Now, developers won’t be able to tear down those homes and build a 25-story tower.”

Under the city’s land-use review procedure, Community Board 9, as of May 7, had 60 days to review the proposal, after which it goes to Stringer, who has a month to review it and suggest changes.

Then it goes to the City Planning Commission, for a 60-day review, and finally, to the City Council, which has 50 days to approve, modify or reject the zoning proposal. Insiders predict it will take effect after some minor tinkering.

Public reviews generally last a maximum of seven months — and that’s a good thing, says state Sen. Bill Perkins, who represents the area.

“There are preservationists in my district who would chain themselves to those brownstones to protect them,” he says.

“Hopefully, that won’t be necessary now, but we always need to be vigilant and skeptical because there have been zoning betrayals in the past, and that’s why we have a public review process.”

Other provisions of the proposed West Harlem zoning plan would:

* Allow commercial uses in a light-manufacturing district between W. 126th St. and W. 130th St. to spur job creation. The so-called mixed-use zone could attract retail and arts companies or other non-profits.

* Direct future larger-scale development to a single block on W. 145th St. between Broadway and Amsterdam Ave. Only on this one site could a residential building rise to 17 stories, and only if it included a significant amount of affordable housing.

* Steer community facilities — like a gym, a library or a halfway house — to commercial and manufacturing corridors by reducing the amount of floor area they’re permitted in residential areas.

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact