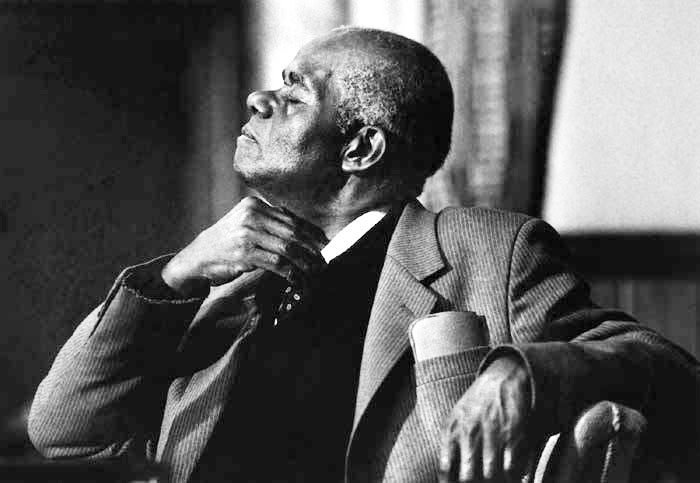

Dr. John Henrik Clarke, born John Henry Clark, January 1, 1915 – July 12, 1998, was a Harlemite, Pan-Africanist writer, historian, professor, and a pioneer in the creation of Africana studies and professional institutions in academia starting in the late 1960s.

Dr. John Henrik Clarke, born John Henry Clark, January 1, 1915 – July 12, 1998, was a Harlemite, Pan-Africanist writer, historian, professor, and a pioneer in the creation of Africana studies and professional institutions in academia starting in the late 1960s.

He was born John Henry Clark on January 1, 1915, in Union Springs, Alabama, the youngest child of sharecroppers John (Doctor) and Willie Ella (Mays) Clark (who died in 1922). With the hopes of earning enough money to buy land rather than sharecrop, his family moved to the nearest mill town, Columbus, Georgia.

…Clarke left Georgia in 1933 by freight train and went to Harlem, New York as part of the Great Migration of rural blacks out of the South to northern cities.

Counter to his mother’s wishes for him to become a farmer, Clarke left Georgia in 1933 by freight train and went to Harlem, New York as part of the Great Migration of rural blacks out of the South to northern cities. There he pursued scholarship and activism. He renamed himself as John Henrik (after rebel Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen) and added an “e” to his surname, spelling it as “Clarke.”

John Henrik Clarke was a professor of Black and Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College of the City University of New York from 1969 to 1986, where he served as founding chairman of the department. He also was the Carter G. Woodson Distinguished Visiting Professor of African History at Cornell University’s Africana Studies and Research Center. Additionally, in 1968 he founded the African Heritage Studies Association and the Black Caucus of the African Studies Association.

In its obituary of John Henrik Clarke, The New York Times noted that the activist’s ascension to professor emeritus at Hunter College was “unusual… without benefit of a high school diploma, let alone a Ph.D.” It acknowledged that “nobody said Professor Clarke wasn’t an academic original.” In 1994, Clarke earned a doctorate from the non-accredited Pacific Western University (now California Miramar University) in Los Angeles, having earned a bachelor’s degree there in 1992.

By the 1920s, the Great Migration and demographic changes had led to a concentration of African Americans living in Harlem. A synergy developed among the artists, writers and musicians and many figured in the Harlem Renaissance. They began to develop supporting structures of study groups and informal workshops to develop newcomers and young people.

He joined study circles such as the Harlem History Club and the Harlem Writers’ Workshop. He studied intermittently at New York University, Columbia University, Hunter College, the New School of Social Research and the League for Professional Writers. He was an autodidact whose mentors included the scholar Arturo Alfonso Schomburg.

Arriving in Harlem at the age of 18 in 1933, Clarke developed as a writer and lecturer during the Great Depression years. He joined study circles such as the Harlem History Club and the Harlem Writers’ Workshop. He studied intermittently at New York University, Columbia University, Hunter College, the New School of Social Research and the League for Professional Writers. He was an autodidact whose mentors included the scholar Arturo Alfonso Schomburg. From 1941 to 1945, Clarke served as a non-commissioned officer in the United States Army Air Forces, ultimately attaining the rank of master sergeant.

In the post-World War II era, there was new artistic development, with small presses and magazines being founded and surviving for brief times. Writers and publishers continued to start new enterprises: Clarke was co-founder of the Harlem Quarterly (1949–51), book review editor of the Negro History Bulletin (1948–52), associate editor of the magazine, Freedomways, and a feature writer for the black-owned Pittsburgh Courier.

Clarke taught at the New School for Social Research from 1956 to 1958. Traveling in West Africa in 1958–59, he met Kwame Nkrumah, whom he had mentored as a student in the US, and was offered a job working as a journalist for the Ghana Evening News. He also lectured at the University of Ghana and elsewhere in Africa, including in Nigeria at the University of Ibadan.

Becoming prominent during the Black Power movement in the 1960s, which began to advocate a kind of black nationalism, Clarke advocated for studies of the African-American experience and the place of Africans in world history. He challenged the views of academic historians and helped shift the way African history was studied and taught. Clarke was “a scholar devoted to redressing what he saw as a systematic and racist suppression and distortion of African history by traditional scholars.” He accused his detractors of having Eurocentric views. His writing included six scholarly books and many scholarly articles. He also edited anthologies of writing by African Americans, as well as collections of his own short stories. In addition, Clarke published general interest articles. In one especially heated controversy, he edited and contributed to an anthology of essays by African Americans attacking the white writer William Styron and his novel, The Confessions of Nat Turner, for his fictional portrayal of the African-American slave known for leading a rebellion in Virginia.

Here is the You Have No friends talk by Dr. Clarke:

Besides teaching at Hunter College and Cornell University, Clarke founded professional associations to support the study of black culture. He was a founder with Leonard Jeffries and first president of the African Heritage Studies Association, which supported scholars in areas of history, culture, literature and the arts. He was a founding member of other organizations to support work in black culture: the Black Academy of Arts and Letters and the African-American Scholars’ Council.

Clarke’s first marriage was to the mother of his daughter Lillie (who died before her father). They divorced.

In 1961, Clarke married Eugenia Evans in New York, and together they had a son and daughter: Nzingha Marie and Sonni Kojo. The marriage ended in divorce.

In 1997, John Henrik Clarke married his longtime companion, Sybil Williams. He died of a heart attack on July 12, 1998, at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital Center. He was buried in Green Acres Cemetery,Columbus, Georgia.

Via Source

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact