July 20, 2014, three days after Eric Garner suffocated to death during an arrest by New York City police officers for selling loose cigarettes, the Reverend Al Sharpton delivered the Sunday sermon at Riverside Church, on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. As befitting the television and radio personality, political power broker, and celebrity he has become—and a man who never learned to drive—Sharpton arrived at Riverside that Sunday morning in his chauffeur-driven black Lincoln Navigator. He was dressed as he almost always is in public these days, in a tailored suit, silk tie, and color-coordinated silk pocket-square. His hair is gray now and worn slicked back. At 61 years old, he is thinner than he has ever been, the result of his rigorous adherence to a mostly vegan diet and a daily exercise routine that have helped him shed more than 150 pounds, about half his weight, or, as Sharpton puts it, “half of my self.”

July 20, 2014, three days after Eric Garner suffocated to death during an arrest by New York City police officers for selling loose cigarettes, the Reverend Al Sharpton delivered the Sunday sermon at Riverside Church, on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. As befitting the television and radio personality, political power broker, and celebrity he has become—and a man who never learned to drive—Sharpton arrived at Riverside that Sunday morning in his chauffeur-driven black Lincoln Navigator. He was dressed as he almost always is in public these days, in a tailored suit, silk tie, and color-coordinated silk pocket-square. His hair is gray now and worn slicked back. At 61 years old, he is thinner than he has ever been, the result of his rigorous adherence to a mostly vegan diet and a daily exercise routine that have helped him shed more than 150 pounds, about half his weight, or, as Sharpton puts it, “half of my self.”

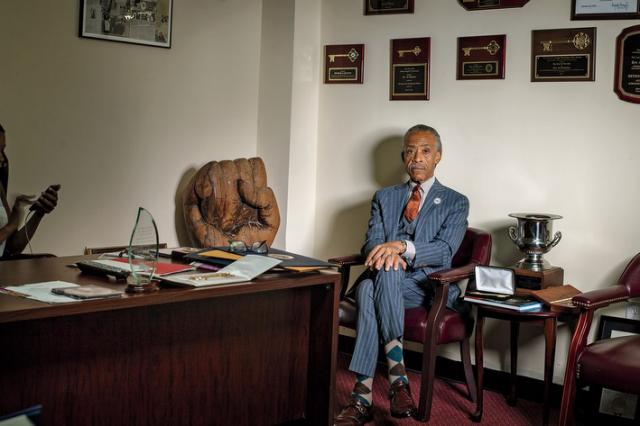

For the sermon, Sharpton wore dark-blue clerical robes over his suit, and, as he stood on the raised, intricately carved limestone pulpit, looking down at the congregation, he seemed, for Al Sharpton, restrained, a little uncomfortable. He was not nervous but aware of the “irony” of his presence on the pulpit at Riverside Church, he says now, sitting in his office, near Times Square: “Whoever thought 20 years ago that Al Sharpton would be preaching at Riverside Church?”

THE THIRD RAIL

Almost everyone these days can claim an Al Sharpton sighting: on his once daily, now weekly, national MSNBC talk show, PoliticsNation; in his cameo on this season’s premiere of Empire; on Charlie Rose, Meet the Press, and the evening news. He appears in the New York tabloids with seeming regularity: REV RAT was the blaring headline in the New York Post last year, heralding the mysterious re-emergence of allegations, backed by documents, that Sharpton was an F.B.I. informant in the 1980s. In person he can be seen at the Grand Havana Room, the private Manhattan cigar club, where he is a member, and at the Regency hotel, the city’s power-breakfast spot, where he was recently seen with Kevin Sheekey, a top aide to former mayor Michael Bloomberg. “Like him or hate him, he is one of the sharpest political minds in the country,” Sheekey told the Daily News after their meeting.

Sharpton’s 60th-birthday party, a lavish affair at the Four Seasons restaurant in October 2014, was emblematic of his status as a member of the city’s Establishment. Among the guests were Mayor Bill de Blasio, New York senator Kirsten Gillibrand, and—popping in from another party—the state’s governor, Andrew Cuomo. In New York today, his relationship with the mayor is said to be so close that some joke that Al Sharpton runs the city. In Washington, Sharpton’s political connections reach into the White House and include President Obama. “A voice of reason” is how Valerie Jarrett, the president’s senior adviser, describes him. “Very constructive, direct,” she says, “willing to take on tough issues and take heat to stand up for what he believes in.”

It has been a remarkable rise to power and influence for a man who was once referred to by former New York mayor Ed Koch as “Al Charlatan”; who has been called a “racial arsonist,” a “race baiter”; who is alternately feared and considered a joke; who is believed to be the model for Reverend Bacon, the bombastic, white-guilt-tripping-for-money, master-media-manipulator, demagogue preacher in Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities; who appeared constantly on TV and in the tabloids, his face contorted with rage—or a good facsimile of it—shouting at the cameras about “crackers” and “punk faggots”; who scuffled with another guest on The Morton Downey Jr. Show in 1988 and fell backward off the stage—all 300 pounds of him. Sharpton’s uniform was often a tracksuit, with a huge brass medallion around his neck, his hair straightened and worn in a pompadour, famously captured by Annie Leibovitz that same year, sitting under a hair dryer at the PrimaDonna Beauty Care Center in Brooklyn. A generation will recall him as the man at the center of one of the most racially charged hoaxes in recent history, the 1987 allegations that Tawana Brawley, a 15-year-old black girl from upstate New York, was raped by a group of white men.

He is still controversial, a human third rail in the racial politics of this country. To his supporters, Sharpton is a man of courage, respected for his willingness to fight by almost whatever means necessary “to give a voice to the voiceless,” as Valerie Jarrett puts it. But he is also loathed by his critics. Pat Lynch, the controversial president of New York’s police union, has called Sharpton “one of the chief extremists fanning the flames of anti-police sentiment for his own gain.” His love of the spotlight has long been mocked, most recently by Larry Wilmore of Comedy Central’s The Nightly Show—where Sharpton has also appeared as a guest—for photo-bombing Obama on the Edmund Pettus Bridge at the 50th anniversary of the march from Selma to Montgomery. “The arc of history always bends towards justice,” Wilmore said. “And Al Sharpton’s face always bends towards the camera.”

In private, says one political journalist, Sharpton will “cause you to have total amnesia about anything to do with him in the 80s and 90s. He is smart. He is charming. He is funny.” But even after so many years in the public eye, he is still an enigma. He was referred to once by a mentor as a man “with separate parts,” of which there are “too many.” He has always been there, but not there; known, but not known: his face so familiar, from the high forehead to the wide mouth, and the one-way eyes that reveal almost nothing about what he’s thinking.

’s early morning, and sunlight streams through the floor-to-ceiling windows of Al Sharpton’s sleek Upper West Side living room. Sharpton is on the phone, pacing back and forth in his navy-blue velour slippers. His girlfriend of six years, Aisha McShaw, a 37-year-old fashion designer and consultant, is in the back room. She drops in to say hello, resplendent in an orange pantsuit by Kimora Lee Simmons. All around, framed photographs fill the bookshelves and line the walls, covering almost every inch of space. Most of them include Sharpton and attest to an important life, one that he has worked so hard to create.

There is Sharpton with Nelson Mandela, with Fidel Castro, with Oprah. And Sharpton when he was seven, dressed in clerical robes, in a church program from 1961. He was famous then in church circles as “the boy preacher,” who toured with Mahalia Jackson, the gospel singer. On the wall in the foyer, there is a photo of Sharpton as a teenager, in 1971, with Huntington Hartford, heir to the A&P fortune, during a boycott of the grocery chain organized by the Reverend Jesse Jackson Sr. There is Sharpton, at 27, with one of his mentors, James Brown, the Godfather of Soul himself, the two of them arriving at the White House, in 1982, with their matching bouffants and three-piece suits. In Sharpton’s book-lined study, there is a huge photograph of him with Barack Obama. Taken in 2007, it hangs above Sharpton’s desk. The two men are standing on a podium, with their arms around each other, the president with his head thrown back laughing.

Sharpton has been up since five A.M., as he is every day. He starts with his prayers—Psalm 37, always, because it “girds me up”: “Fret not thyself because of evildoers, neither be thou envious against the workers of iniquity”—and then moves on to making his calls and sending e-mails starting around 5:30, after exercising in the gym in his apartment building.

His is a punishing schedule. In addition to three hours of talk radio daily, at his studio at 30 Rock, he does his TV show and more radio on weekends, and he travels constantly. In two weeks recently, Sharpton was in Washington, D.C., three times—twice for White House meetings and receptions, and back again for a meeting with Bernie Sanders. He was in San Diego to give a speech to the United Domestic Workers union, then Los Angeles to preach at two churches back-to-back on a Sunday morning, and protest at the Oscars in the afternoon, before heading back to New York that night.

Al Sharpton knows what critics say about him—ambulance chaser, media whore, a man without substance. “I think that America is uncomfortable with the issue of race,” he says, “and anyone that comes to the front, to embody that, to personify that, is going to inherit that discomfort. And the more dramatic you are, the more hostility is ingrained. People think I am taking advantage, that I am an opportunist,” he says. “At least my critics ought to give me credit for: ‘This is his life’s work.’ Did I make mistakes? Yeah. Did I stumble? But don’t act like that ain’t what I really have done all my life.”

THE PRODIGY

Sharpton’s father, Alfred senior, owned a small grocery store but made the bulk of his money as “a slumlord,” Sharpton wrote in his memoirs. He bought up properties in Brooklyn and Queens. When Sharpton was five, the family moved from Brooklyn to the leafy middle-class neighborhood of Hollis, Queens, where they owned a house with a yard, and Sharpton’s father bought two Cadillacs every year, one for himself and one for his wife.

Sharpton was an unusual child—very bright and precocious. Even at a young age, he was fascinated by preaching. He’d started when he was about three; dressing up in his mother’s bathrobe, he’d preach to his sister’s dolls, imitating their pastor, Bishop Frederick Douglass Washington, almost word for word. His mother, who was a devout Pentecostalist, encouraged him; she even had little pews built in the basement of their Queens home. He was four years old when he preached in public for the first time, at the Washington Temple Church of God in Christ, an influential Pentecostal church in Brooklyn, where Sharpton was ordained as a minister when he was 10 years old.

To many, it was clear that “there was a divine calling on his life,” says the Reverend Herbert Daughtry, the prominent civil-rights activist, who met Sharpton when he was about 12. “He was a boy prodigy,” says the Reverend Jesse Jackson Sr., who first met Sharpton a few years later. He was so serious, Jackson recalls, “he was like an old man.”

Sharpton was nine when his father left home. Alfred senior had begun an affair with his stepdaughter—Sharpton’s 18-year-old half-sister, from his mother’s first marriage—and they had a son shortly after they moved out of the family home in Queens. The trauma for Sharpton was enormous. His mother almost had a nervous breakdown. Without support from his father, the family was financially overwhelmed. The electricity was cut off, the car was repossessed, and the family went on welfare. They eventually moved to a Brooklyn public housing project, and Sharpton’s mother went to work as a maid. After her pocketbook was snatched on her way to work, Sharpton would get up every morning and walk her to the subway. “She used to hide her cleaning rag, because she didn’t want my friends to know she was a domestic worker. And I used to always say, ‘I’m gonna make her proud.’ ” His voice catches, as it often does when he speaks of Ada Sharpton, once breaking down in tears during a 2013 interview with Oprah, 18 months after his mother died.

Looking back, Sharpton says those years after his father walked out were critical to who he became. “I learned how to duck these situations of being laughed at by my friends. We went from me being the boy preacher, where they were handing out flyers to come hear me preach, to: ‘That’s the kid whose dad knocked up his sister.’ And I’m only 9 or 10 years old. I guess in many ways I was conditioned for being ridiculed and controversial since I was nine. ‘Cause I always, I developed a thick skin and a loner thing.”

Dr.. King had come to speak at Washington Temple, as had some of the Freedom Riders, but it was the Sharpton family’s move to the projects that galvanized Sharpton’s interest in civil rights. He was about 11, he says, when he began to notice “the conditions that black people not only lived in but accepted as inevitable in the projects”: garbage wasn’t picked up; ambulances didn’t show up for 90 minutes or more.

It was New York City, “Malcolm X’s town, not King’s,” in those days, as Sharpton puts it, and his mother was afraid that her son would come under the influence of the more radical separatist and nationalist factions of the movement. So she took him to meet William Augustus Jones Jr., the well-known Baptist minister and civil-rights leader who worked with Dr. King. Jennifer Jones Austin, Jones’s daughter, is C.E.O. of the social-services agency F.P.W.A., a former adviser to Mayor de Blasio, and a member of the Bloomberg and Giuliani administrations. She says her father became one of several “mentors/fathers,” older, prominent men whom Sharpton would adopt and who—in the absence of his father, with whom he would not speak for decades—would shape his life. There was Bishop Washington, who taught him to preach and introduced him to Mahalia Jackson; Adam Clayton Powell Jr., the famous Harlem congressman, who gave Sharpton his first glimpse of what “real power” wielded by a black man looked like. From the Reverend Jones—who later re-baptized Sharpton as a Baptist—he learned to read the great theologians, and met the movement’s leading ministers, including Dr. King. And from Jesse Jackson—who was “young, brash, had a huge Afro, and wore a medallion”—Sharpton gained a role model for what a young, church-based civil-rights leader could be.

A King acolyte, Jackson was national director of Operation Breadbasket, the economic-empowerment arm of King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (S.C.L.C.). Sharpton volunteered for Operation Breadbasket, and took over its youth operation in 1969, when he was 14. Fearing he’d “burn out,” like so many other child prodigies, Jackson pushed him to go to college. Sharpton did so, attending Brooklyn College for two years, before he got bored and dropped out. “Here come the boy wonder,” Jackson would say, greeting him sarcastically after that. “Ain’t gonna be nothing but a Harlem fanatic.”

But Sharpton, says Jackson, “did not burn out. He kept remaking himself. He always had a mind like a sponge that could absorb.” And he was deliberate and focused, working, as he does now, up to 16 hours a day. What he wanted, says Jackson, was “to be a leader, with the power to make a difference. He didn’t justhappen to be a leader. He really meant to be one, and he has pursued getting enough power through relationships to achieve his purpose.”

After Jesse Jackson left the S.C.L.C. in 1971, Sharpton started his own group, the National Youth Movement. Again, he had the backing from prominent older men, this time Harlem leaders, including the Manhattan borough president, Percy Sutton, and Clarence Jones, the editor and publisher of The Amsterdam News. The group’s mission was to fight drugs and raise money for impoverished black youth, and to raise the funds from local businesses. It would involve Sharpton in the kind of deals—portrayed in the media as playing on white guilt and fear for money—that would give him the reputation of a “hustler,” as The New Yorker put it in 1993. The 70s and early 80s were years when Sharpton seemed less a minister or a civil-rights anything and more a music-business operator. In those days the real money in concert promotion went to whites, even when the audiences and the stars were black. He pressured managers and artists to use black promoters—often himself. He became close friends with Mike Tyson, Michael Jackson, and the boxing impresario Don King. The relationship with King led to one of his lowest moments—getting ensnared in an F.B.I. sting against the promoter, in which Sharpton was secretly videotaped in 1983 discussing a cocaine deal with an undercover agent.

“They tried to entrap me on tape—and by their admission, they didn’t—to commit a crime. I answered all their questions and did whatever they wanted with Don King’s investigation,” Sharpton says. He denies reports that he became an F.B.I. informant to avoid federal drug charges, or prevent the release of the video. He did provide information to the F.B.I. about the Mafia around that time, he says, because it had threatened his life in a music-business turf war.

Sharpton’s most important and longest-running relationship in the entertainment world had begun earlier, in 1973, when he helped James Brown promote two benefit concerts in Brooklyn, bringing in 8,000 kids. For Sharpton, Brown became the closest thing to a father he’d had. It was Brown who told Sharpton to change his name from Alfred to “Al”—“Reverend Al” was catchier—and who insisted he wear his hair in a “conk” like his so they would look more like father and son. In 1980, Sharpton, who’d had a very brief first marriage, married a backup singer for Brown, Kathy Jordan—from whom he has been legally separated since 2004, and with whom he has two daughters, Dominique, now 29, and Ashley, 28. Brown would help support Sharpton financially, even paying the private-school tuitions of his daughters.

Not merely a great artist, but a master performer, “James Brown was a huge influence,” says Jennifer Jones Austin, who has known Sharpton since childhood. It was the “celebrity piece” that Sharpton got from Brown, the canny understanding of the theatrics of politics and protest.

TAWANA BRAWLEY

With Brawley’s lawyers C. Vernon Mason and Alton Maddox, Sharpton turned the incident into “this unbelievable, theatrical performance that went on for months and months,” says the author Dan Zegart, who covered the Brawley case for a local paper. After a lengthy investigation, a grand jury concluded that Brawley had concocted the story of her abduction and rape. Investigators theorized that she was afraid of her stepfather’s anger because she had broken her curfew. But Sharpton continued his campaign, driven, some believe, by his vanity, ambition, and yearning for recognition to do what he may have come to suspect, at some deep level, was wrong.

“He came off of Howard Beach with a righteous victory,” says Zegart. “With Brawley you had Sharpton really trying to be the civil-rights leader that he always wanted to be, but it was just an elaborate con.” In 1998, Steven Pagones, the assistant district attorney accused of rape, won a defamation suit against Brawley and her advisers. Johnnie Cochran, the trial lawyer best known for his defense of O. J. Simpson, was among several supporters who helped pay Sharpton’s $65,000 share of the judgment, in 2001. Tawana Brawley, last known to be living in Virginia, is paying her settlement—with interest now more than $430,000—by having her wages as a nurse garnished by the court.

To this day, Sharpton has never retracted his accusations or apologized. He says that “as a minister” what happened to Pagones does bother him. “I’ve thought about it a million times,” he says. “I wrestle with his life being upended.” But he parses the Brawley case like a lawyer; each individual decision he made was correct, so the whole must be right. What should he apologize for: Believing the lawyers? Believing a teenager who said she was the victim of a terrible crime? “If I say I’m sorry I believed them, then I am sorry I believe Eric Garner, and I’m sorry I believe Michael Brown. I mean: what are you supposed to say?” He has never met with Pagones. “If this guy and I sat down, I would say, ‘I had just done Howard Beach. Why the hell would I want to fabricate something on you?’ ” he says. “If he was falsely accused, then clearly all of us ran out there on something that wasn’t true, and [the person] who said it should apologize,” he says, referring to Brawley—remarkably, after all these years, still pushing the blame for his actions on her.

In April 1989, two years after the “attack” on Brawley, one Hispanic and four black teenagers were arrested for the rape and near-fatal beating of a white woman who had been jogging in Central Park. Convicted in 1990, they spent from 7 to 13 years in prison before they were exonerated, when the real rapist confessed. The case rocked New York and is memorable for the screaming, full-page ad that Donald Trump took out inThe New York Times, the Daily News, the Post, and Newsday in 1989 calling for the death penalty for the teenagers—and for Sharpton’s insistence from the outset that the young men were innocent. “How come our generation never remembers that I was out there by myself on the Central Park case?” he says. “How come you never read that a man tried to kill me and I forgave him and went to visit him in jail?” he says of the incident in 1991 when he was knifed by a white man at a demonstration against the murder of a young black man by a white mob in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. The virulent racism in Bensonhurst stunned New Yorkers—crowds yelling, “Niggers, go home,” and holding up watermelons to mock black marchers—but Sharpton gained little respect from the city’s political establishment in the process of bringing it to light.

If so few seemed to be listening to him, it was because, some say, he had squandered so much of his credibility on Brawley. From then on, he became for many a bad joke, and much of what he did would be perceived as self-promoting publicity stunts.

EPIPHANY

Sharpton, says Eric Garner’s widow, Esaw, “gave me a voice for my husband’s death not to be in vain.” He also stepped in to help financially—with money for the funeral, a son’s schoolbooks, and a new laptop. “I feel so bad sometimes when I hear all the negative things people say about him, because I’ve seen none of that and I’ve been around him for the last year and 60 days, to be exact,” says Garner. “And I’ve never seen him ask any victim for any money. I’ve never seen him tell any of the victims he has to pay them back. He’s never told me that. He’s never insinuated that. He’s never said to me, ‘Oh, Esaw, when you get your’—he’s never even mentioned the settlement,” she says, referring to the $5.9 million wrongful-death settlement the family received from the city of New York in July 2015.

Opinions differ. One of Garner’s own daughters suggested on video that Sharpton used the grieving families to promote himself and NAN. She complained that NAN scolded her for not displaying its logo on flyers she had printed. Rubbing her thumb and forefingers together, indicating “money,” she said of Sharpton, “He’s about this.” Her grandmother Gwen Carr says she was quoted “out of context,” and indeed the hidden-camera interview was conducted by the conservative group Project Veritas, in what seemed like an attempt to discredit Sharpton.

Money and Sharpton have long had an uneasy relationship. In 2014, records indicated that he had accumulated about $4.5 million in state and federal tax liens against himself and his for-profit businesses, in which he invested income from such things as speaking engagements. His finances have been investigated several times—notably by New York State in the wake of the Brawley case, when he was charged on and acquitted of 67 counts of fraud and larceny, including misappropriating National Youth Movement funds, and in 2004 by the Federal Election Commission, which fined him and his campaign committee $208,000 for using funds from NAN and his own private companies to finance his presidential campaign that year. In 2007, F.B.I. and I.R.S. agents, armed with subpoenas, converged on the homes of several top NAN staff members, as part of an investigation of a number of financial issues, including, says Sharpton, a tip that claimed NAN was paying nonexistent employees, and that Sharpton was pocketing the money. What emerged from that was a giant federal tax bill and liens, at one point close to $2 million, for unpaid payroll taxes—part of a dispute, Sharpton says, in which several independent contractors had to be reclassified as employees. In a 2006 report citing poor recordkeeping, unpaid taxes, debts, and lawsuits, accountants said NAN’s future as a going concern was in doubt. There were years when it was kept alive partly by money Sharpton lent it—which amounted to $328,881 by 2013.

Sharpton himself travels first-class and stays in the top hotels. Most of his travel, a spokesperson says, is paid for by groups that invite him to speak, not NAN. Yet NAN’s debts still piled up. It was sued by the Peabody Hotel in Memphis for $88,000 in unpaid bills, by a travel agent for $50,000, and by the landlord of its Arizona office for $30,000. “I think the reality is that, as with most civil-rights groups, we struggle to raise money. Sometimes we over-extended ourselves, assuming we were going to raise things we didn’t raise,” says Sharpton. “One of the things about being raised by everybody from James Brown to Jesse Jackson, who all had tax issues, [is that] I never learned administration. I am not a great fiscal manager.” About four years ago, Sharpton’s longtime friend and lawyer, Michael Hardy, closed his law firm, moved into NAN’s corporate offices, and took over the organization’s finances. Payment agreements were negotiated, lawsuits settled, and slowly NAN’s debts, and Sharpton’s, were reduced. Last October, the final $644,665 of NAN’s debt to the I.R.S. was paid off. In April 2015, Sharpton himself paid off nearly $1 million in personal back taxes, reportedly leaving him with $3.5 million to repay, although he insists it is less than the public records show, “minuscule,” he says.

NAN has benefited from Sharpton’s growing influence in political circles. In 2014, contributions to NAN reached a record high—nearly $7 million, slightly more than a $2 million increase over the year before. With a membership that is not wealthy, much of that money comes from corporate donors. Sharpton’s birthday party at the Four Seasons alone raised $1 million in one night for NAN, from such corporations as AT&T, Walmart, Verizon, McDonald’s, and GE Asset Management. Donating to NAN, for many companies, is a way of reaching an important consumer. But this flow of money has also led to accusations that Sharpton has sold “cover” on minority issues to white corporate America, a sort of Racial Housekeeping Seal of Approval.

Allegations that companies pay outright, or otherwise reward, Sharpton, NAN, and other civil-rights groups were made in a 2015 lawsuit filed by Byron Allen, a cable-television entrepreneur, against Comcast and Time Warner Cable. The suit claimed that the cable companies did virtually no business with “100% African-American owned media companies” but rewarded civil-rights groups for helping to persuade federal regulators that their merger would not adversely affect minority TV businesses and customers. Comcast called the suit “frivolous,” and the court dismissed the case against Sharpton and the civil-rights groups—but it did not help perceptions that, just seven months after Comcast bought NBC, Sharpton was given his own hour-long daily show on MSNBC, a gig that today pays him more than $750,000 a year. Phil Griffin, the president of MSNBC, denies there was a trade-off. “Emphatically no,” he says, insisting that bringing Sharpton on board was his idea, and that it was a controversial decision at NBC.

THE FIGHTER

Everybody, Sharpton says, recalling the race, was “shocked that I am not wearing a tracksuit, and I know three words past ‘No justice, no peace.’ Low expectations has always been my secret weapon.” He pulled in 15 percent of the statewide vote, and almost 70 percent of the black vote. “How did I get that vote?” he asks. “I preached all over the state, in every church.”

But what catapulted Sharpton to the national political stage was his 2004 presidential campaign. He stood no chance of winning, and he had no interest in the job, but it was part of his strategy, he says, to boost his visibility nationwide, and to get the message out “that the Democratic Party was acting like elephants with donkey clothes on.” There were moments during the primary debates when he came across as the most reasonable man on the stage. “Sharpton was at his best. He was funny. He was pointed. He was tremendously politically effective,” says Walter Shapiro, the political columnist and author of One-Car Caravan, a political memoir about the 2004 primaries.

DEAR BROTHER AL

r their first one-on-one meeting, in November 2007, Barack Obama and Al Sharpton had dinner at Sylvia’s, the Harlem power restaurant. It was where he later met Caroline Kennedy, in her bid for his political benediction during her unsuccessful quest for Hillary Clinton’s U.S. Senate seat, in 2008, and most recently with Bernie Sanders. Obama had southern-fried chicken and collard greens; Sharpton drank tea—he had already embarked on his austere diet. (Two pieces of whole-wheat toast for breakfast and dinner; salad, two hard-boiled eggs, and a banana for lunch.) Obama had come to Sharpton to explain his candidacy; Sharpton’s hometown senator, Hillary Clinton, was in the race, so Obama, says Sharpton, was surprised when he said he would endorse him. “He is a formidable ally,” says Jesse Jackson of Sharpton’s efforts on Obama’s behalf. “He has argued the president’s case, using his credibility when the president may not have been so well known.”

In the 2012 election, the White House was “very nervous that the black turnout would be lower than 2008,” says Shapiro. It eventually clocked in at nearly 67 percent, which was an important element to Obama’s win. Sharpton was aggressive in calling attention to the urgency of the issue of voting rights. “We almost single-handedly made voter ID an issue,” he says. “A lot of the reason people lined up was—yes, they loved Obama, but it was because they felt we were being robbed of our right to vote.”

Sharpton’s backing of Obama has occasionally cost him in the black community, where some see Obama not as a black leader as much as a leader who is black. Cornel West, the prominent activist and former Princeton professor, who has been on the front lines of protests from Ferguson to Baltimore, has attacked Sharpton for his allegiance to the president. In one of his increasingly colorful and incendiary comments, West referred to “our dear brother Al Sharpton” as “the bona fide house Negro of the Obama plantation.”

For Sharpton’s supporters, that sort of talk from West and other African-American critics is rooted in envy. “A lot of the negatives are over access,” says one top Sharpton ally. “Cornel West has never been to the White House under Obama.” But is Sharpton’s access only about fealty? With 18 hours a week of talk radio, until recently 5 hours of television—now 1 on Sunday mornings due to an MSNBC reshuffling—and preaching at churches around the country, Sharpton has the means to bring people out, and onto the street, if necessary. Which is the silent threat. “Was it that Barack Obama said, ‘I need this man to hold hands with me because I don’t want him out there challenging me?’ ” asks one New York politico. “Does Bill de Blasio bring him in the camp because he doesn’t want him out there being the Al Sharpton that he knows he can be?” says this person, because “you don’t want Sharpton coming at you.”

SWEAT AND BLOOD

Sharpton’s dream has always been to be a civil-rights leader, the “anointed” leader, says Reverend Daughtry. But at the very moment that this leadership seems to be in his grasp, is it slipping away from him? “I run a civil-rights organization. It is almost insulting to act like blacks are only one-dimensional, it’s just them against the cops,” he says, alluding to the fact that most of the protest groups today are focused on police violence. “What about health care? What about all the other things, [how we fought] to keep Obama in—the whole wide array of things?” he asks. “When I went out for Trayvon, it was the same thing: ‘Sharpton’s an outsider,’ ‘Sharpton is Old Guard.’ Well, those groups are gone, and we are still dealing with ‘stand your ground.’ Where do the Garners go to? Who handles Chicago? It is good what [these groups] do because it heightens attention. But to go on, you need more than just attention.” Sharpton’s message may be getting through: in Baltimore, 30-year-old DeRay Mckesson, a leading Black Lives Matter activist, is running for mayor.

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact