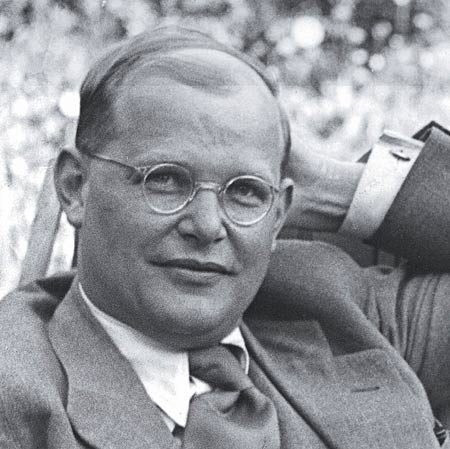

Dietrich Bonhoeffer (German: [ˈdiːtʁɪç ˈboːnhœfɐ]; 4 February 1906 – 9 April 1945) was a German Lutheran pastor, theologian, anti-Nazi dissident, key founding member of the Confessing Church and Harlemite in the 1920’s. His writings on Christianity’s role in the secular world have become widely influential, and his book The Cost of Discipleship became a modern classic.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer (German: [ˈdiːtʁɪç ˈboːnhœfɐ]; 4 February 1906 – 9 April 1945) was a German Lutheran pastor, theologian, anti-Nazi dissident, key founding member of the Confessing Church and Harlemite in the 1920’s. His writings on Christianity’s role in the secular world have become widely influential, and his book The Cost of Discipleship became a modern classic.

Apart from his theological writings, Bonhoeffer was known for his staunch resistance to the Nazi dictatorship, including vocal opposition to Hitler’s euthanasia program and genocidal persecution of the Jews. He was arrested in April 1943 by the Gestapo and imprisoned at Tegel prison for one and a half years. Later he was transferred to a Nazi concentration camp. After being associated with the plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler, he was quickly tried, along with other accused plotters, including former members of the Abwehr (the German Military Intelligence Office), and then executed by hanging on 9 April 1945 as the Nazi regime was collapsing.

Bonhoeffer was born on 4 February 1906 in Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland), into a large family. In addition to his other siblings, Dietrich had a twin sister, Sabine Bonhoeffer Leibholz: he and Sabine were the sixth and seventh children out of eight. His father was psychiatrist and neurologist Karl Bonhoeffer. His mother Paula Bonhoeffer, née von Hase, was a teacher and the granddaughter of Protestant theologian Karl von Hase and painter Stanislaus Kalckreuth. His oldest brother Karl Friedrich Bonhoeffer became a chemist, and, along with Paul Harteck, discovered the spin isomers of hydrogen in 1929. Walter Bonhoeffer, the second born of the Bonhoeffer family, was killed in action during World War I, when the twins were 12. The third Bonhoeffer child, Klaus, was involved in the 20 July plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler, along with Dietrich; he, too, was executed by the Nazis. Both of Bonhoeffer’s older sisters, Ursula Bonhoeffer Schleicher and Christel Bonhoeffer von Dohnanyi, married men who were eventually executed by the Nazis. Christel was imprisoned by the Nazis but survived. Sabine and their youngest sister Susanne Bonhoeffer Dress each married men who survived Nazism. His cousin Karl-Günther von Hase was the German Ambassador to the United Kingdom from 1970 to 1977.

Bonhoeffer completed his Staatsexamen, the equivalent of both a bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree, at the Protestant Faculty of Theology of the University. He went on to complete his Doctor of Theology degree (Dr. theol.) from [Berlin University] in 1927, graduating ‘summa cum laude’.

…in 1930 for postgraduate study and a teaching fellowship at New York City’s Union Theological Seminary… He studied under Reinhold Niebuhr and met Frank Fisher, a black fellow seminarian who introduced him to Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, where Bonhoeffer taught Sunday school…. He heard Adam Clayton Powell, Sr., preach the Gospel of Social Justice and became sensitive to not only social injustices experienced by minorities but also the ineptitude of the church to bring about integration.

Still too young to be ordained, the 24-year-old Bonhoeffer went to the United States in 1930 for postgraduate study and a teaching fellowship at New York City’s Union Theological Seminary. Although Bonhoeffer found the American seminary not up to his exacting German standards (“There is no theology here.”), he had life-changing experiences and friendships. He studied under Reinhold Niebuhr and met Frank Fisher, a black fellow seminarian who introduced him to Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, where Bonhoeffer taught Sunday school and formed a lifelong love for African-American spirituals, a collection of which he took back to Germany. He heard Adam Clayton Powell, Sr., preach the Gospel of Social Justice and became sensitive to not only social injustices experienced by minorities but also the ineptitude of the church to bring about integration. Bonhoeffer began to see things “from below”—from the perspective of those who suffer oppression. He observed, “Here one can truly speak and hear about sin and grace and the love of God…the Black Christ is preached with rapturous passion and vision.” Later Bonhoeffer referred to his impressions abroad as the point at which he “turned from phraseology to reality.” He also learned to drive an automobile, although he failed the driving test three times. He traveled by car through the United States to Mexico, where he had been invited to speak on the subject of peace. His early visits to Italy, Libya, Spain, the United States, Mexico, and Cuba opened Bonhoeffer to ecumenism.

After returning to Germany in 1931, Bonhoeffer became a lecturer in systematic theology at the University of Berlin. Deeply interested in ecumenism, he was appointed by the World Alliance for Promoting International Friendship through the Churches (a forerunner of the World Council of Churches) as one of its three European youth secretaries. At this time he seems to have undergone something of a personal conversion from being a theologian primarily attracted to the intellectual side of Christianity to being a dedicated man of faith, resolved to carry out the teaching of Christ as he found it revealed in the Gospels. On 15 November 1931—at the age of 25—he was ordained at the Old-Prussian United St. Matthew’s Church (German: St. Matthäuskirche) in Berlin.

Bonhoeffer’s promising academic and ecclesiastical career was dramatically altered with Nazi ascension to power on 30 January 1933. He was a determined opponent of the regime from its first days. Two days after Hitler was installed as Chancellor, Bonhoeffer delivered a radio address in which he attacked Hitler and warned Germany against slipping into an idolatrous cult of the Führer (leader), who could very well turn out to be Verführer (mis-leader, or seducer). He was cut off the air in the middle of a sentence, though it is unclear whether the newly elected Nazi regime was responsible.[9] In April 1933, Bonhoeffer raised the first voice for church resistance to Hitler’s persecution of Jews, declaring that the church must not simply “bandage the victims under the wheel, but jam the spoke in the wheel itself.” In retrospect, his famous speech can be seen as anti-semitic, and playing into the hands of the Nazi regime. He ascribed the suffering of the Jews to God’s righteous punishment for the killing of Jesus. He used the anti-semitic terminology “Jewish problem”, and accepted the authority of the state to deal with the “problem” as it saw fit.

In November 1932, two months before the Nazi takeover, there had been an election for presbyters and synodals (church officials) of the German Landeskirche (Protestant established churches). This election was marked by a struggle within the Old-Prussian Union Evangelical Church between the nationalistic German Christian (Deutsche Christen) movement and Young Reformers—a struggle which threatened to explode into schism. In July 1933, Hitler unconstitutionally imposed new church elections. Bonhoeffer put all his efforts into the election, campaigning for the selection of independent, non-Nazi officials.

Despite Bonhoeffer’s efforts, in the rigged July election an overwhelming majority of key church positions went to Nazi-supported Deutsche Christen people. The Deutsche Christen won a majority in the general synod of the Old-Prussian Union Evangelical Church and all its provincial synods except Westphalia, and in synods of all other Protestant church bodies, except for the Lutheran churches of Bavaria, Hanover, and Württemberg. The non-Nazi opposition regarded these bodies as uncorrupted “intact churches”, as opposed to the other so-called “destroyed churches.”

In opposition to Nazification, Bonhoeffer urged an interdict upon all pastoral services (baptisms, weddings, funerals, etc.), but Karl Barth and others advised against such a radical proposal. In August 1933, Bonhoeffer and Hermann Sasse were deputized by opposition church leaders to draft the Bethel Confession, a new statement of faith in opposition to the Deutsche Christen movement. Notable for affirming God’s faithfulness to Jews as His chosen people, the Bethel Confession was so watered down to make it more palatable that Bonhoeffer ultimately refused to sign it.

In September 1933, the national church synod at Wittenberg voluntarily passed a resolution to apply the Aryan paragraph within the church, meaning that pastors and church officials of Jewish descent were to be removed from their posts. Regarding this as an affront to the principle of baptism, Martin Niemöller founded the Pfarrernotbund (Pastors’ Emergency League). In November, a rally of 20,000 Deutsche Christens demanded the removal of the Old Testament from the Bible, which was seen by many as heresy, further swelling the ranks of the Emergency League.

Within weeks of its founding, more than a third of German pastors had joined the Emergency League. It was the forerunner of the Bekennende Kirche (Confessing Church), which aimed to preserve traditional Christian beliefs and practices. The Barmen Declaration, drafted by Barth in May 1934 and adopted by the Confessing Church, insisted that Christ, not the Führer, was the head of the church. The adoption of the declaration has often been viewed as a triumph, although by Wilhelm Niemöller’s estimate, only 20% of German pastors were supporting the Confessing Church.

When Bonhoeffer was offered a parish post in eastern Berlin in the autumn of 1933, he refused it in protest at the nationalist policy, and accepted a two-year appointment as a pastor of two German-speaking Protestant churches in London: the German Lutheran Church in Dacres Road, Sydenham. and the German Reformed Church of St Paul’s, Goulston Street, Whitechapel. He explained to Barth that he had found little support for his views—even among friends—and that “it was about time to go for a while into the desert”, Barth regarded this as running away from real battle. He sharply rebuked Bonhoeffer, saying, “I can only reply to all the reasons and excuses which you put forward: ‘And what of the German Church?'” Barth accused Bonhoeffer of abandoning his post and wasting his “splendid theological armory” while “the house of your church is on fire” and chided him to return to Berlin “by the next ship.”

Bonhoeffer however did not go to England simply to avoid trouble at home, but he had hoped to put the ecumenical movement to work in the interest of the Confessing Church. He continued his involvement with the Confessing Church, running up a high telephone bill to maintain his contact with Martin Niemöller. In international gatherings, Bonhoeffer rallied people to oppose the Deutsche Christen movement and its attempt to amalgamate Nazi nationalism with the Christian gospel. When Bishop Theodor Heckel—the official in charge of German Lutheran Church foreign affairs—traveled to London to warn Bonhoeffer to abstain from any ecumenical activity not directly authorized by Berlin, Bonhoeffer refused to abstain.

In 1935, Bonhoeffer was presented with a much-sought-after opportunity to study non-violent resistance under Gandhi in his ashram, but, perhaps remembering Barth’s rebuke, decided to return to Germany in order to head an underground seminary for training Confessing Church pastors in Finkenwalde. As the Nazi suppression of the Confessing Church intensified, Barth was driven back to Switzerland in 1935; Niemöller was arrested in July 1937; and in August 1936, Bonhoeffer’s authorization to teach at the University of Berlin was revoked after he was denounced as a “pacifist and enemy of the state” by Theodor Heckel.

Bonhoeffer’s efforts for the underground seminaries included securing necessary funds, and he found a great benefactor in Ruth von Kleist-Retzow. In times of trouble, Bonhoeffer’s former students and their wives would take refuge in von Kleist-Retzow’s Pomeranian estate, and Bonhoeffer was a frequent guest. Later he fell in love with Kleist-Retzow’s granddaughter Maria von Wedemeyer, to whom he became engaged three months before his arrest. By August 1937, Himmler decreed the education and examination of Confessing Church ministry candidates illegal. In September 1937, the Gestapo closed the seminary at Finkenwalde and by November arrested 27 pastors and former students. It was around this time that Bonhoeffer published his best-known book, The Cost of Discipleship, a study on the Sermon on the Mount, in which he not only attacked “cheap grace” as a cover for ethical laxity but also preached “costly grace”.

Bonhoeffer spent the next two years secretly traveling from one eastern German village to another to conduct “seminary on the run” supervision of his students, most of whom were working illegally in small parishes within the old-Prussian Ecclesiastical Province of Pomerania. The von Blumenthal family hosted the seminary in its estate of Groß Schlönwitz. The pastors of Groß Schlönwitz and neighbouring villages supported the education by employing and housing the students (among whom was Eberhard Bethge, who later edited Bonhoeffer’s “Letters and Papers from Prison”) as vicars in their congregations. Bonhoeffer’s friendship with Bethge, whom he considered a soulmate, was intense and possessive, and had the markings of an unrequited romance.

In 1938, the Gestapo banned Bonhoeffer from Berlin. In summer 1939, the seminary was able to move to Sigurdshof, an outlying estate (Vorwerk) of the von Kleist family in Wendish Tychow. In March 1940, the Gestapo shut down the seminary there following the outbreak of World War II. Bonhoeffer’s monastic communal life and teaching at Finkenwalde seminary formed the basis of his books, The Cost of Discipleship and Life Together.

Bonhoeffer’s sister Sabine, along with her Jewish-classified husband Gerhard Leibholz and their two daughters, escaped to England by way of Switzerland in September 1940.

In February 1938, Bonhoeffer made an initial contact with members of the German Resistance when his brother-in-law Hans von Dohnányi introduced him to a group seeking Hitler’s overthrow at Abwehr, German military intelligence.

Bonhoeffer also learned from Dohnányi that war was imminent and was particularly troubled by the prospect of being conscripted. As a committed pacifist opposed to the Nazi regime, he could never swear an oath to Hitler and fight in his army. Not to do so was potentially a capital offense. He worried also about consequences his refusing military service could have for the Confessing Church, as it was a move that would be frowned upon by most Christians and their churches at the time.[24]

It was at this juncture that Bonhoeffer left for the United States in June 1939 at the invitation of Union Theological Seminary in New York. Amid much inner turmoil, he soon regretted his decision despite strong pressures from his friends to stay in the United States. He wrote to Reinhold Niebuhr: “I have come to the conclusion that I made a mistake in coming to America. I must live through this difficult period in our national history with the people of Germany. I will have no right to participate in the reconstruction of Christian life in Germany after the war if I do not share the trials of this time with my people… Christians in Germany will have to face the terrible alternative of either willing the defeat of their nation in order that Christian civilization may survive or willing the victory of their nation and thereby destroying civilization. I know which of these alternatives I must choose but I cannot make that choice from security.” He returned to Germany on the last scheduled steamer to cross the Atlantic.

Back in Germany, Bonhoeffer was further harassed by the Nazi authorities as he was forbidden to speak in public and was required to regularly report his activities to the police. In 1941, he was forbidden to print or to publish. In the meantime, Bonhoeffer joined the Abwehr (a German military intelligence organization). Dohnányi, already part of the Abwehr, brought him into the organization on the claim his wide ecumenical contacts would be of use to Germany, thus protecting him from conscription to active service. Bonhoeffer presumably knew about various 1943 plots against Hitler through Dohnányi, who was actively involved in the planning. In the face of Nazi atrocities, the full scale of which Bonhoeffer learned through the Abwehr, he concluded that “the ultimate question for a responsible man to ask is not how he is to extricate himself heroically from the affair, but how the coming generation shall continue to live.” He did not justify his action but accepted that he was taking guilt upon himself as he wrote “when a man takes guilt upon himself in responsibility, he imputes his guilt to himself and no one else. He answers for it… Before other men he is justified by dire necessity; before himself he is acquitted by his conscience, but before God he hopes only for grace.” (In a 1932 sermon, Bonhoeffer said: “the blood of martyrs might once again be demanded, but this blood, if we really have the courage and loyalty to shed it, will not be innocent, shining like that of the first witnesses for the faith. On our blood lies heavy guilt, the guilt of the unprofitable servant who is cast into outer darkness.”

Under cover of the Abwehr, Bonhoeffer served as a courier for the German resistance movement to reveal its existence and intentions to the allies in hope of garnering their support, and, through his ecumenical contacts abroad, to secure possible peace terms with the Allies for a post-Hitler government. His visits to Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland were camouflaged as legitimate intelligence activities for the Abwehr. In May 1942, he met Anglican Bishop George Bell of Chichester, a member of the House of Lords and an ally of the Confessing Church, contacted by Bonhoeffer’s exiled brother-in-law Leibholz; through him feelers were sent to British foreign minister Anthony Eden. However, the British government ignored these, as it had all other approaches from the German resistance. Dohnányi and Bonhoeffer were also involved in Abwehr operations to help German Jews escape to Switzerland. During this time Bonhoeffer worked on Ethics and wrote letters to keep up the spirits of his former students. He intended Ethics as his magnum opus, but it remained unfinished when he was arrested. On 5 April 1943, Bonhoeffer and Dohnányi were arrested and imprisoned.

For a year and a half, Bonhoeffer was imprisoned at Tegel military prison awaiting trial. There he continued his work in religious outreach among his fellow prisoners and guards. Sympathetic guards helped smuggle his letters out of prison to Eberhard Bethge and others, and these uncensored letters were posthumously published in Letters and Papers from Prison. One of those guards, a Corporal named Knobloch, even offered to help him escape from the prison and “disappear” with him, and plans were made for that end. But Bonhoeffer declined it fearing Nazi retribution on his family, especially his brother Klaus and brother-in-law Hans von Dohnányi who were also imprisoned.

After the failure of the 20 July Plot on Hitler’s life in 1944 and the discovery in September 1944 of secret Abwehr documents relating to the conspiracy, Bonhoeffer’s connection with the conspirators was discovered. He was transferred from the military prison Tegel in Berlin, where he had been held for 18 months, to the detention cellar of the house prison of the Reich Security Head Office, the Gestapo’s high-security prison. In February 1945, he was secretly moved to Buchenwald concentration camp, and finally to Flossenbürg concentration camp.

On 4 April 1945, the diaries of Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, head of the Abwehr, were discovered, and in a rage upon reading them, Hitler ordered that the Abwehr conspirators be destroyed. Bonhoeffer was led away just as he concluded his final Sunday service and asked an English prisoner Payne Best to remember him to Bishop George Bell of Chichester if he should ever reach his home: “This is the end—for me the beginning of life.”

Bonhoeffer was condemned to death on 8 April 1945 by SS judge Otto Thorbeck at a drumhead court-martial without witnesses, records of proceedings or a defense in Flossenbürg concentration camp. He was executed there by hanging at dawn on 9 April 1945, just two weeks before soldiers from the United States 90th and 97th Infantry Divisions liberated the camp, three weeks before the Soviet capture of Berlin and a month before the capitulation of Nazi Germany.

Bonhoeffer was stripped of his clothing and led naked into the execution yard, where he was hanged, along with fellow conspirators Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, Canaris’s deputy GeneralHans Oster, military jurist General Karl Sack, General Friedrich von Rabenau, businessman Theodor Strünck, and German resistance fighter Ludwig Gehre. Bonhoeffer’s brother, Klaus Bonhoeffer, and his brother-in-law Rüdiger Schleicher were executed in Berlin on the night of 22–23 April as Soviet troops were already fighting in the capital. His brother-in-law Hans von Dohnányi had been executed in Sachsenhausen concentration camp on 8 or 9 April.

Eberhard Bethge, a student and friend of Bonhoeffer’s, writes of a man who saw the execution: “I saw Pastor Bonhoeffer… kneeling on the floor praying fervently to God. I was most deeply moved by the way this lovable man prayed, so devout and so certain that God heard his prayer. At the place of execution, he again said a short prayer and then climbed the few steps to the gallows, brave and composed. His death ensued after a few seconds. In the almost fifty years that I worked as a doctor, I have hardly ever seen a man die so entirely submissive to the will of God.”

Such is the traditional account of Bonhoeffer’s death. Over the decades it achieved almost the status of an epitaph; for instance, Eric Metaxas‘s best-selling biography quotes it without comment. But many recent biographers see problems with the story, not due to Bethge but his source. The purported witness was a doctor at Flossenbürg concentration camp, Hermann Fischer-Hüllstrung who may have wished to minimize the suffering of the condemned men to reduce his own culpability in their executions. J.L.F. Mogensen, a former prisoner at Flossenbürg, cited the length of time it took for the execution to be completed (almost six hours), plus departures from ordinary camp procedure that hardly would have been allowed the prisoners so late in the war, as jarring inconsistencies. Considering that the sentences had been confirmed at the highest levels of Nazi government, by individuals with a pattern of torturing prisoners who dared to challenge the regime, it is more likely that “the physical details of Bonhoeffer’s death may have been much more difficult than we earlier had imagined.”

Other recent critics of the traditional account are more caustic. One terms the Fischer-Hüllstrung story as “unfortunately a lie,” citing additional factual inconsistencies (the doctor described Bonhoeffer climbing the steps to the noose, but at Flossenbürg the gallows had none), and observing that “Fischer-Hüllstrung had the job of reviving political prisoners after they had been hanged until they were almost dead, in order to prolong the agony of their dying.” Another charges that Fischer-Hüllstrung’s “subsequent statement about Bonhoeffer as kneeling in wordy prayer . . . belongs to the realm of legend.”

Bonhoeffer is commemorated as a theologian and martyr by the United Methodist Church, Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and several church members of the Anglican Communion including the Episcopal Church (USA) on the anniversary of his death, 9 April.

The Deutsche Evangelische Kirche in Sydenham, London, at which he preached between 1933 and 1935, was destroyed by bombing in 1944. A replacement church was built in 1958 and named Dietrich-Bonhoeffer-Kirche in his honor.

Via source

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact