This was A’Lelia Walker’s, back in the day from 1885-1931, it was a home and famous salon, “The Dark Tower,” which she hosted for writers, musicians, artists at 108 West 136th Street in Harlem during the 1920s. It was named after a sonnet by queer poet Countee Cullen, which has been said to capture the spirit of the Harlem Renaissance.

A’Lelia Walker’s fortune came from her mother, Madame C.J. Walker, an enterprising woman who created a million-dollar empire from beauty salons and hair-straightening products for black women, and who died in 1931.

A’Lelia Walker—born Lelia Walker (she changed her name in 1922)—was the only child of Madam C.J. Walker, an entrepreneur and hair care industry pioneer who is recognized as America’s first self-made female millionaire. (Her Irvington, New York, home, Villa Lewaro, is a National Treasure of the National Trust for Historic Preservation.)

Madam Walker’s hair care empire had grown tremendously, and A’Lelia convinced her to expand into New York City. And so in 1913, Madam Walker purchased a townhouse on 108 West 136th Street in Harlem. Two years later, the Walkers acquired the adjacent townhouse at 110 West 136th Street. They hired noted architect Vertner Woodson Tandy to do a complete remodel, turning the two townhouses into one sprawling unit. Tandy was one of the first practicing African-American architects; he went on to design Madam C.J. Walker’s Villa Lewaro.

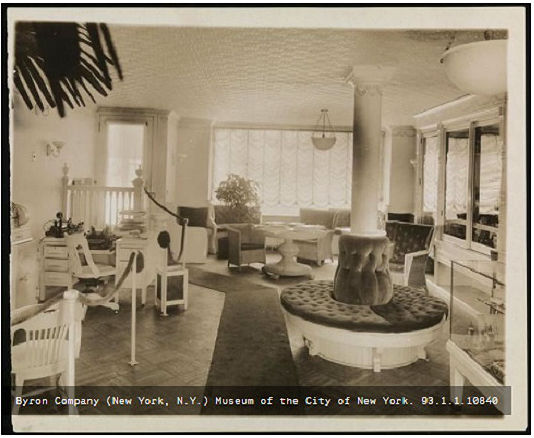

With her inheritance, A’Lelia purchased these two Vertner Tandy,-designed townhouses on West 136th Street in “Sugar Hill,” combined them into one residence with a new façade, and furnished them lavishly (see below).

Here the woman dubbed “the Mahogany Millionairess” hosted cultural soirees for the Harlem and Greenwich Village “glitterati,” white and black, serving caviar and bootleg champagne and providing entertainment by queer performers and others like Alberta Hunter, Jimmy Daniels, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, W.E.B. Du Bois, Muriel Draper, Nora Holt, Witter Bynner, Andy Razaf, Taylor Gordon, Carl Van Vechten, Clarence Darrow, James Weldon Johnson and many others.

Langston Hughes later wrote that A’Lelia’s parties “were as crowded as the New York subway at the rush hour.” She herself was a striking figure, whom Hughes called Langston Hughes called Walker “the joy goddess of Harlem’s 1920s,” and “a gorgeous dark Amazon.”

We shall not always plant while others reap

The golden increment of bursting fruit,

Not always countenance, abject and mute,

That lesser men should hold their brothers cheap;

Not everlastingly while others sleep

Shall we beguile their limbs with mellow flute,

Not always bend to some more subtle brute;

We were not made to eternally weep.The night whose sable breast relieves the stark,

White stars is no less lovely being dark,

And there are buds that cannot bloom at all

In light, but crumple, piteous, and fall;

So in the dark we hide the heart that bleeds,

And wait, and tend our agonizing seeds.– “From the Dark Tower,” by Countee Cullen

Saving Places writes that in 1927, Walker hired designer Paul T. Frankl to redecorate the Walker Studio. One element he added to the space was a custom-designed “Skyscraper” bookcase, named for its architectural characteristics.

In October 1927, the Dark Tower—envisioned as a private membership club—officially opened in a room within the Walker Studio, which had now expanded to the second and third floors of the townhouse. And Frankl’s “Skyscraper” bookcase became its logo, of sorts, appearing on the Dark Tower’s stationary and invitations. The gatherings at the townhouse continued.

“These parties had all the artists, musicians, writers, actors who were part of the Harlem Renaissance, but it was also the newspaper publishers, the Civil Rights leaders—everybody, at some point,” Bundles says. “It was very much a central location for the Harlem Renaissance.”

One year after opening, in October 1928, the Dark Tower closed. Walker had begun charging for food and refreshments, which was a hard adjustment for many to make. She continued to rent the townhouse out for events, and she continued her arts patronage and philanthropic endeavors. But in 1929, the market crashed. Fewer parties were thrown during the Depression.

Walker died in 1931. After that point, the townhouse was rented out to the City of New York, which used the space for a health clinic. Then in 1941, the townhouse was demolished. In its place, the New York Public Library built what would become its Countee Cullen Branch.

Sadly, Walker’s historic home was demolished by the city in 1941. The Countee Cullen branch of the New York Public Library now stands on the site at located on 108-110 West 136th Street between 6th and 7th Avenue (today’s Malcolm X and Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard).

Photo credit: 1-5) Pictures from National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact