Nestled in the heart of Atlanta’s University Center, Morehouse College is a beacon of black male excellence.

Nestled in the heart of Atlanta’s University Center, Morehouse College is a beacon of black male excellence.

Here, commencement is a celebration not simply of the newly minted graduating class,but also of the countless Morehouse Men who have paved the way for their brothers throughout the all-male college’s 148-year history — among them, Spike Lee, Samuel L. Jackson, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.The archetypal Morehouse Man, distinguished and exceptional, is a classic man in every sense: educated, suited up, and deeply invested in his community. He is hailed on campus and throughout black communities well outside Atlanta — even earning a nod from President Obama himself during his controversial 2013 commencement address at the College.

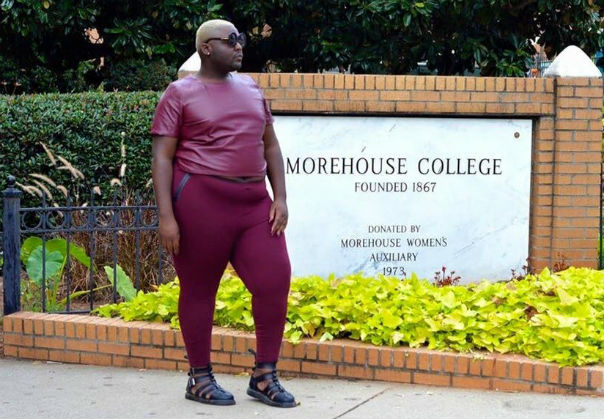

But for class of 2014 graduate Jamal Lewis, returning to campus to see friends walk Morehouse’s decorated stage this past May was a reminder of the ways this storied brotherhood does not always extend to all students. Lewis, who was raised in Atlanta, returned to campus wearing a shirt that said “Morehouse Fag.”

“What that shirt really meant for me in that moment was that I was Other, and ‘fag’ was the only language that I had to really capture that otherness,” Lewis, who uses “he/she” pronouns and identifies outside the gender binary, told BuzzFeed News. “I constantly, on the daily, fail black manhood and black womanhood. And for me, ‘fag’ is just that space that lies in between the two — it’s very political, very abject, very meaningful to me because I’m not trying to ascend into a respectable gender.”

Despite seeming like an especially bold proclamation to some, the shirt garnered a response no different from the kind of gawking Lewis has long grown accustomed to experiencing on campus. Lewis’s college years were a time of constantly weighing the desire to simply express his/herself authentically against the danger or humiliation that same expression might garner in public spaces like the campus libraries, walkways, and cafeteria.

“Many people were staring at me … which was nothing new,” Lewis said. “Had I had on something else outside of that ‘Morehouse Fag’ T-shirt, people still would’ve looked at me strangely because they just read my body … or rather, see my gender, as unintelligible.”

For Lewis, and countless other students whose genders do not fall neatly into the binary ascribed to them by the world at large, the balancing act of calling out their classmates’ and institution’s queerphobia without feeding into harmful stereotypes about black people is a difficult one. Both black masculinity and black femininity are already subject to immense scrutiny and stigma in a climate that measures acceptable gender roles by their proximity to white masculinity. To call out a community already at the margins is to risk that critique being amplified by dominant voices — with the effect of further stigmatizing both groups one belongs to.

Black people are often depicted as being inherently more homophobic than other groups, despite the reality that they are more likely to identify as LGBT and more likely to vote in favor of marriage equality than their white counterparts. This misconception, fueled partly by the work of white gay activists who erroneously blamed the 2008 passage of California’s anti-marriage equality Proposition 8 on black voters, erases the work and experiences of black people who are queer and/or trans themselves.

As single-sex campuses around the country begin to publicly grapple with the expanding expressions of gender identity, historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are often left out of the national dialogue. The face of queer activism — on campuses or otherwise — is often white, affluent, and masculine. But queerness on HBCU campuses, where diversity defies simple categorization, challenges assumptions about race, gender, and sexuality alike.

Morehouse’s very founding, only two years after the end of the Civil War, was itself a testament to the omnipresent obstacle of anti-black racism in America. Morehouse — and so many other HBCUs — came to existence chiefly because black people were actively excluded from the educational opportunities afforded to whites. Though black students are no longer legally barred from attending predominately white colleges, educational institutions continue to discriminate against people of color, especially those from low-income communities, at every level.

And living under the intersecting burdens of (perceived) gender and/or sexual deviance as well as anti-blackness in America makes some students especially vulnerable — even in spaces ostensibly created for all black students to thrive. For queer and gender-nonconforming Morehouse students, this means either accepting intra-community policing of their gender and sexuality (like the controversial 2009 banning of “women’s attire”) — or finding ways to speak out against it and shift campus culture.

At Morehouse, gender and sexuality hold as much complexity as blackness. Here, against the backdrop of (and sometimes alongside) Atlanta’s vibrant queer communities, students find ways to express themselves across expansive, intersecting identity spectrums. The gender-nonconforming “Mean Girls of Morehouse” explicitly challenged the college’s dress code in heels and makeup; more masculine-presenting queer men rebel against patriarchal standards in quieter ways.

Lewis, who uses the pronoun “he/she” precisely because it “really reckons with the gender binary head on and it’s just very vulgar and perfect,” contends that the definition of the Morehouse Man is an all too narrow one. Rather than celebrating the diversity within black masculinities, “the Morehouse Man that Morehouse chooses to uplift and promote is the one that is a very ‘Talented Tenth,’ very black respectable negro, a black exceptional negro,” he/she said. For students whose understanding of their own genders doesn’t fit neatly into this static vision of masculinity, aspiring to that ideal can be a Sisyphean task — one that Lewis, who “disidentifies” with the label, has no interest in.

Yet even within a climate that privileges “respectable” expressions of masculinity, Lewis found spaces to reckon with suppression of his/her gender and challenge the status quo.Morehouse College SafeSpace, the school’s alliance for gender and sexual diversities, gives students an outlet, political home, and community. For Lewis, who organized with the group all four years of his/her time at Morehouse, SafeSpace served as home base. In the tradition of black queer organizing, it addresses instances of discrimination and hostility while proactively pushing the administration to offer more concrete support to LGBT students. Black queer students undertaking that activist work do so knowing that they must struggle not only against the homophobia they face, but also against deeply entrenched perceptions of black people as being inherently homophobic. SafeSpace offers a refuge from both.

Shareef Phillips, a current Morehouse junior, told BuzzFeed News that the simple act of providing outlets for students to speak candidly about their own experiences is part of what makes SafeSpace so integral to his livelihood on campus.

“We have an event every year where different people on the panel talk about their coming out stories, and how they came out, and how long it took them to come out, and the things they went through to come out,” Phillips said. “So just hearing different people’s perspectives on coming out, it definitely helps you come out yourself and know that you’re not alone.”

The group also serves to foster nuanced dialogue within the college and on a national scale. When an open letter to the Morehouse football team was published in 2014 by a white moviegoer who found the team’s vocal disdain for a gay film character deplorable, SafeSpace’s then-president, Marcus Lee, responded by highlighting not only how the team misstepped, but also how those attitudes are shaped in the world more broadly — and how they might be fixed. In an op-ed, he noted that the institution of Morehouse itself was complicit in supporting these attitudes, despite some individuals (including the president of the college) embracing the LGBT community in words, if not also in action.

“There are no Black queer studies courses, gender and sexual orientation are absent from our employment nondiscrimination policy, we have a dress code that outlaws wearing ‘female attire,’ we have an inactive diversity committee, and the list continues,” Lee wrote. “So, I don’t think the football team’s reactions are inherent to them specifically. Instead, they are a product of a grooming process — that begins in the world, and is buttressed or goes uninterrupted at Morehouse — that’s checkered with heteronormativity and silence; inclusive spaces are forged here in spite of, not because of, the culture of the college.”

Indeed, it is the diligent, deeply personal political work of queer student activists at Morehouse and beyond that has catalyzed the institution’s push to support its LGBT community more substantively. In 2012, SafeSpace collaborated with the Sociology department to advocate for a new course: “History and Culture of Black LGBT,” an “interdisciplinary survey of Black lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) culture and politics,” as reported by the Maroon Tiger. The class was taught by Yale University professor and noted Africana studies scholar Dr. Jafari S. Allen, but it was only offered for one semester.

Where academia fails to offer sustained opportunities for critical gender and sexuality inquiry, students forge their own spaces for it. One such example, the “Bayard Rustin Scholars” program, was named after the queer advisor to Dr. King. Rustin is often erased from civil rights movement retellings because of his sexuality. The program gives incoming freshmen the chance to learn from a targeted social justice curriculum conceived by Lewis, Lee, and another student, Kenneth Maurice Pass. For Lewis, a vision of Morehouse offering students the opportunity to be their whole selves is not only realistic, it’s in line with the institution’s liberatory founding.

“There is a complexity to struggle, and I’m just not really interested in pathologizing Morehouse and how black men respond to sexual and gender deviance. But I’m interested in challenging and critically holding them accountable,” Lewis said. “Morehouse should be a place where black men are getting free, and that freedom comes from a scholarship that challenges them to reckon with the ills of the world.”

Lewis got the opportunity to address those ills, in the tradition of James Baldwin and Audre Lorde, by writing through — and away from — them, in pieces for the student paper the Maroon Tiger. The Tiger, though not a space not officially designated as being queer, challenges campus norms and offers queer students an outlet to speak up and speak back.

“For so long I was only writing as a contributing writer, but the time that I came in [as an admin] was — as Drake and Future say — it was that time to be alive,” Lewis said. “Both the editor-in-chief and managing editor were queer; they were my colleagues, they were my contemporaries, and they valued the insight that I brought to the table, so together with our strengths we were able to accomplish really amazing things.”

Among those accomplishments was the publication of a “Body Issue,” in which students wrote candidly about the traumas, subjugation, and experiences their bodies have withstood. The issue, which was criticized by some students when it first debuted for being“too gay,” is one example of what Lewis calls the queerness inherent in journalism that pushes the status quo.

“Instead of showcasing the bodies we want, we showcase the bodies we have … adding this historical narrative around black people and their bodies and subjugation and trauma — bodies holding history, and bodies as a map,” Lewis said. “We were able to produce an issue that confronted sexual assault, substance abuse and addiction, and sexuality and hair and all of those things that our bodies carry.”

The Tiger offered Lewis the chance to quite literally re-write narratives about gender on campus, but it is not the only arena in which queer students confront rigid standards of masculinity and build community. In the end, it’s the relationships between queer and trans students themselves that are really inciting change.

“I wasn’t really sure if I was going to come to Morehouse because before I came to Morehouse I was kinda struggling with who I was — if I was attracted to girls or was I attracted to guys,” Phillips said. “I didn’t really think it was a good idea A) to go to an HBCU, and B) for it to be an all male institution.”

But joining SafeSpace expanded Phillips’ understanding of HBCU campus cultures. “I had the wrong perception of what Morehouse was about,” he said. “Toward the end of [my first] semester I came across people who were part of the LGBTQ community. And the more and more I started hanging out with them, I figured out that’s where I need to be; that’s where I feel most comfortable.”

Perhaps the group’s most important function is as a support network. It was through SafeSpace that Phillips met Lewis — and found the people who made him feel emboldened to both come out and begin to present more femininely.

Lewis cites slowly changing tides as one of the most rewarding aspects of the activist work he/she undertook while at Morehouse, and the motivation behind projects like Femme To Femme and #QueerHBCU that he/she is working on now. The ability to help create an environment in which younger students feel more free to express themselves and “embody their wholeness” is not an opportunity Lewis takes lightly.

“We all know as black queer people that safety has never been granted to us. It was beautiful to see that the safe space that we [alumni] created lived on in the students and in the resilience that they embody day to day on campus,” Lewis said. “That’s one thing I’m proud of — that we never really had an official space, but we had a space because it lived within the students.”

“I got to see that when I came back home; it almost moved me to tears and I could cry now,” Lewis continued. “For so long I felt alone walking that campus and coming back for homecoming, to see my children as I call them, just storming the campus, just at home within their own bodies and with their own selves — just whole — it was amazing to see.”

When Phillips participated in an androgyny-themed photo shoot for a campus magazine, rocking a crop top and a face full of makeup, some fellow students said his hyper-feminine look was “not what a Morehouse Man stands for.” The remarks — few and far between in a sea of mostly supportive comments from friends — set him back internally, making him wonder if he needed to tone down his normal feminine presentation. But following in the footsteps of queer and trans students carried Phillips through the discomfort of that pushback.

“Jamal [Lewis] was one of the main people, but it was a lot of other people that was just being themselves on campus,” Phillips said. “And I thought ‘hey, I want to be one of those people, I don’t want to shelter myself from the things I want to do.’”

Phillips is hopeful about Morehouse’s direction moving forward, asking simply that campus continue to evolve toward being more open-minded and understanding that all students’ gender expression is valid and need not be questioned or mocked.

“I’m able to do androgynous shoots or dress this way and do this while getting my studies done and matriculating throughout Morehouse to get my degree,” he said. “I’m doing the same thing everybody else is doing, but just doing it in a different way.

“At the end of the day we’re still your brothers, or sisters, however you identify.”

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact