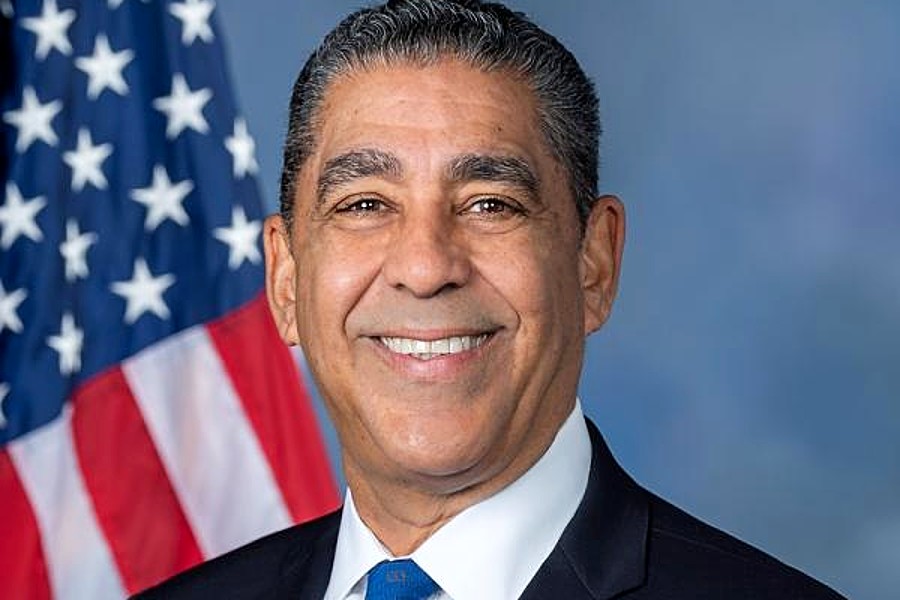

On a December night in 2003, at Rao’s, the legendary restaurant on Pleasant Avenue in East Harlem, a man nicknamed Louie Lump Lump (pictured above) shot another patron after reportedly taking issue with his disparaging comment about the female singer’s rendition of “Don’t Rain on My Parade” from “Funny Girl.” The incident felt like a tale from a bygone era and garnered a great deal of giddily nostalgic local press. One patron told The Daily News, “I was surprised. Things like that don’t happen here.” At least not in recent decades.

On a December night in 2003, at Rao’s, the legendary restaurant on Pleasant Avenue in East Harlem, a man nicknamed Louie Lump Lump (pictured above) shot another patron after reportedly taking issue with his disparaging comment about the female singer’s rendition of “Don’t Rain on My Parade” from “Funny Girl.” The incident felt like a tale from a bygone era and garnered a great deal of giddily nostalgic local press. One patron told The Daily News, “I was surprised. Things like that don’t happen here.” At least not in recent decades.

The first time I ever saw Pleasant Avenue was in “The Godfather.” Long before I knew where it was, I watched Sonny Corleone bound across it and thrash his wife-beating brother-in-law with a garbage-can lid. A 10-year-old kid in suburban Michigan, I was thunderstruck. For years, it remained my favorite single mob movie moment, followed closely by Henry Hill pistol-whipping the man who assaulted his girlfriend in “Goodfellas.” The scenes speak to all the romantic, ill-founded notions of the mob that I grew up with and that, even after I became a writer of crime fiction, have proved embarrassingly hard to shake off.

Pleasant Avenue isn’t just one of the most storied streets in organized crime history.

But I’m not just a mob aficionado; I’m also a grant writer for Union Settlement Association, a social-service agency in East Harlem that has weathered the neighborhood’s struggles with poverty, gangs and drugs for more than 100 years. And Pleasant Avenue isn’t just one of the most storied streets in organized crime history; it’s also the site of the mammoth red-brick-and-limestone building that houses the Manhattan Center for Science and Mathematics and the Isaac Newton Middle School for Math and Science, where we run an after-school program. Whenever I walk down Pleasant Avenue, I feel these worlds collide.

Bounded by Jefferson Park to the south and 120th Street at its northern tip, Pleasant Avenue spans a mere six blocks and is essentially a cul-de-sac, protected from the din, on either side, of First Avenue and Franklin D. Roosevelt Drive. For more than 50 years, the area was a stronghold of Sicilian mob activity, from the early days of Lupo the Wolf and his brother-in-law, known as the Clutching Hand, to the days of Fat Tony Salerno, who picked union presidents from his Manhattan headquarters at the Palma Boy Social Club, until his indictment in 1985.

At one point, nearly every bakery and candy store on the avenue was purported to be a “policy bank” where you could gamble — play your numbers and take your chances. From the late 1940s until a major drug bust in 1973, in which nearly 100 gangsters were arrested, Pleasant Avenue was rumored to have processed and distributed half the heroin in the United States. Those six blocks were, according to the writer Ernest Volkman, a “virtual open-air narcotics flea market.” Inside each of the tenements were “cut houses,” where shifts of women would cut and weigh the heroin, diluting it with milk sugar and placing it in bags. Supposedly, they worked in the nude, either to prevent them from stealing or because of the heat in those close quarters. Local teens were then dispatched as “movers,” delivering the $5 bags of heroin to waiting cars. “If you knew the right people,” David Durk and Ira Silverman wrote in “The Pleasant Avenue Connection,” their 1976 exposé, “you could go there at three in the morning and borrow 50,000 dollars in cash or rent a submachine gun or arrange to fix a judge or pick up three kilos of heroin.”

A few days ago, walking by a knot of those old tenements, I thought about all this, and about the fact that today, perhaps, Pleasant Avenue wouldn’t be known to the rest of the city at all were it not for Rao’s, one of the few remaining landmarks on the strip. When I ask Steven Portericker, who heads the after-school services at Union Settlement, about Rao’s, he smiles knowingly. He grew up on 111th Street in the ’80s, and by then, the mob presence was more legend than day-to-day reality. “You’d hear things,” he said. “But you’d never see anything. After school, we’d stand on every corner of the avenue, like kids do. But we never stood in front of Rao’s. In fact, we’d walk on the other side of the street. None of us ever even crossed the street.”

He looks a little surprised. “I don’t think I ever have,” he says.

To the students at Isaac Newton and the Manhattan Center, those mob tales are little more than a whisper, if that. They have the daily concerns of all young teens, added to the specific concerns of those who go to school in a neighborhood battling high dropout rates and few opportunities. But while the names Lucchese and Genovese mean nothing to them, there remains a kind of freighted quality to the one particular corner of the street where Rao’s sits. After school you’ll see kids hanging out outside every store and restaurant except for that one. It’s as if Rao’s has absorbed all the mystery and dread that has faded from the rest of Pleasant Avenue.

“It’s private,” says Bryana, age 14. “For Italians.”

“For rich people,” corrects her classmate Kaydee. “I see baseball players going in and out.” Many of the students come from other neighborhoods, some from as far away as Brooklyn, but Kaydee grew up on Pleasant Avenue and bears the knowing look of a true insider. All eyes widen when she says she has been to Rao’s. It’s not a brag. “My mom knows the owner,” she says, smiling a little. “So we all went.” She adds that the place is small and the food tasted good and that they were treated nicely.

When I ask Bryana if she would like to go, she shakes her head firmly. “No. You never know what’s going to happen there.”

And yet not much seems to anymore. The most shocking thing that’s happened there since the 2003 shooting was the visit, last year, by the cast of “Top Chef,” in an episode titled “An Offer They Can’t Refuse.” Lorraine Bracco from “The Sopranos” served as guest judge.

In any case, Bryana and Kaydee don’t have to — and perhaps shouldn’t — look down the street for a good story. Instead of indulging my own weakness for the area’s pulp lore, I could be sharing with them a far richer and more telling stretch of local history, one that lies right under their feet. The school building was originally the home of Benjamin Franklin High School. It was founded in 1934 and headed by the city’s first Italian-American high school principal, Leonard Covello, whose guiding principle was “community-centered” education that embraced all the neighborhood’s immigrant cultures. In 1945, after violence in the school escalated between Italian- and African-American students, Frank Sinatra visited, spoke about ethnic tolerance and sang “Aren’t You Glad You’re You?” In the audience was the future jazz musician Sonny Rollins, who later said the event changed his life.

And yet, even knowing all this — having the gift of a larger context — the little girl in me enthralled by “The Godfather” reemerges. I still can’t help but be drawn to Rao’s. The following day I walk by again. Somehow I seem to think I can figure something out if I look closely enough.

It’s not open yet, but I peer through the wrought iron gate and the windows festooned with poinsettias and a small statue of Our Lady of Mount Carmel. While I can’t see any movement, I imagine the chopping of onions, the mincing of garlic. There is a warm glow inside the deep red heart of the place. Along with the sense of good food and nostalgia is the sheen that comes from exclusivity, from mystery. But also from just lasting. It’s 4 o’clock. They’re getting ready for the night.

Related articles

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact