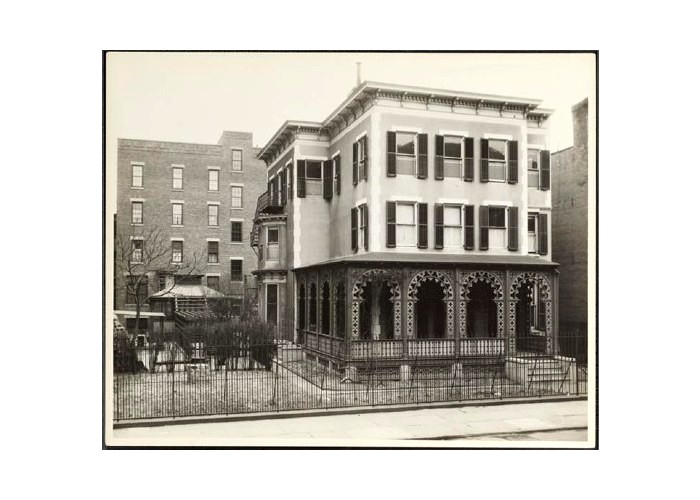

The legendary amazing Moorish architecture home at 12 West 129th Street, Harlem, New York, was erected in1863.

Harlem was undergoing development as a suburban center, stands as a rare survivor of Harlem‘s early history, prior to its rapid development as an urban neighborhood.

Built for two carpenters, William Paul and Thomas Wilson, and their families, it was a two-and-a-half-story frame structure characteristic of suburban architecture.

Subsequent changes to the house reflect adaptations by new owners to their needs, as well as changes in the surrounding community.

In 1883, piano merchant John Bolton Simpson, Jr., added the distinctive Moorish-inspired porch, the most significant architectural feature of the house, with its perforated ornamentation created by the use of a scroll saw.

In 1896, the house was acquired by an order of Franciscan nuns which was expanding its mission in the greater New York area.

In order to accommodate a new use as a convent and children’s home, the building was enlarged to a full three stories.

Since that time, the building has continued in institutional ownership; it was purchased in 1979 by the Christ Temple Church of the Apostolic Faith, which plans to convert it to a senior citizens’ residence.

History and Development

Harlem, originally known as New Harlem (named for the Dutch city of Haarlem), was established by Dutch governor Peter Stuyvesant in 1658.

Harlem’s boundaries incorporated much of northern Manhattan, extending as far south as what is now East 74th Street near York Avenue.

Most of the land in Harlem was divided into farms in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, with a small village established on the banks of the Harlem River to the south of present-day 125th Street.

The village was an important social and political center in northern Manhattan, with its houses, court, inn, and Dutch Reformed Church.

Although by 1683 Harlem was considered a part of the city and county of New York, it remained a modestly populated rural community, relatively untouched by urban development until the mid-nineteenth century.

As transportation links between Harlem and New York City to the south improved in the course of the nineteenth century, change began to occur in northern Manhattan, especially in the village on the Harlem River.

New York City’s first railroad, the New York and Harlem Railroad, was incorporated in 1831 and, by the summer of 1837, was running steam trains to Harlem along Fourth Avenue (now Park Avenue).’

The presence of the railroad brought development to the village and by 1866, when the first New York City atlas depicting Harlem was published, many of the streets located to the east of Fourth Avenue had taken on an urban character/ The atlas plates show the location of such important urban amenities as a firehouse and a police station, as well as a substantial number of houses, several churches, and a number of factories and lumber and coal yards.

These buildings faced the grid of rectangular streets that had been laid over most of Manhattan between Houston Street and 155th Street in 1811.

To the west of the built-up village, blocks were streets with freestanding suburban homes. Among these was the house erected in about 1863 at 12 West 129th Street

History of its Construction and Occupancy

The land on which 12 West 129th Street was erected had been owned by Arent Haimanse Bussing, one of the original Harlem patentees/ Bussing, a native of Westphalia, appears to have arrived in Harlem as a militiaman.

By the time of his death in 1718, he owned 127 acres of land in Harlem. At the death of his grandson, Aaron Bussing, in 1730, the property was still intact.

According to New York City records, Aaron Bussing’s executors conveyed the property to John Adriance in 1787/ The Adriance family remained involved with the block until 1844.

After passing through several hands, the three twenty-five-foot wide lots that now comprise the site of 12 West 129th Street were purchased in 1862 by William Paul.

At the time that he purchased the Harlem property, Paul was a carpenter with his business at 86 West 24th Street and a residence nearby at 188 West 24th Street.

He shared his house with another carpenter, Thomas Wilson.

City directories indicate that by 1864, Paul and Wilson were business partners; they were also sharing a new two-and-one-half-story house located on West 129th Street between Fifth and Sixth (later Lenox) avenues (now No. 12 West 129th Street).

A-frame structure with a gabled roof, the house was probably characteristic of the Italianate suburban residence type

It is unclear whether the new Harlem house was erected by Paul, by Wilson, or by both carpenters. Thomas Wilson is recorded as living in the house as of 1863-64, while Paul is not recorded at this address until the following year.

The house at No. 12 was not the first dwelling on the south side of West 129th Street between Fifth and Sixth avenues. To the west of the Paul/Wilson house was a pair of Greek Revival dwellings, probably erected in the 1840s/ The 1866 atlas shows other suburban dwellings to the east, including a neighboring house owned by Joseph Dudley, a druggist, and a comer house owned by Walter Brady who was in the real estate business.

William Paul lived on West 129th Street for only about two years; in 1865 he and his wife Frances conveyed the property to Thomas Wilson, and the Pauls then moved to West 127th Street.

The United States Census of 1870 records that Thomas Wilson was a fifty-year-old builder (between 1871 and 1874, city directories list Wilson as a builder; before 1871 and after 1874 he is listed as a carpenter), and a native of Maine, who lived in the house with his two daughters and two sons and a single Irish-bom female servant.

In 1872, Thomas Wilson moved to Bast 128th Street and sold the West 129th Street property to Martin England, a printer who was a native of Newfoundland.

England resided in the house with his wife, son, two daughters, and two servants/ Although the England family retained ownership of the property until 1896, they apparently left the house following Martin England’s death c.1881.

Beginning in 1882, No. 12 West 129th Street was leased to John Boulton Simpson, Jr. Simpson was a piano merchant who, in 1885, was a founder of the Estey Piano Company, along with Jacob Estey.

The Estey company was famous for its organs, manufactured in Vermont. In order to break into the lucrative piano business, Estey became associated with John B. Simpson, Jr., who previously had been involved with the Arion Piano Company which had offices on East 14th Street and its factory on East 129th Street.

The Estey Piano Company erected a substantial factory complex on Southern Boulevard (now Bruckner Boulevard) and Lincoln Avenue in the Bronx, a site that could easily be reached from Harlem via the Third Avenue and Madison Avenue bridges.

In about 1893, Simpson left the West 129th Street house, moving to the Adirondack town of Bolton in Warren County.

At the time that the Simpson family moved to No. 12 West 129th Street, Harlem was beginning to undergo rapid change as urban development swept into northern Manhattan.

This development was caused by major improvements in mass transit. Improved service on the New York and Harlem Railroad, notably the opening of the first Grand Central Terminal in 1875 and the construction of a four-track system with tracks running on trestles, made commuting more convenient.

This service was augmented between 1878 and 1880 by the inauguration of service on three elevated rail lines — on Second, Third, and Eighth avenues.

In fact, by the 1880s, extensive development had occurred on West 129th Street between Fifth and Lenox avenues with the construction of Italianate and Victorian Gothic rowhouses.

Nearby, on West 130th Street between Fifth and Lenox avenues, Astor Row (the houses are designated New York City Landmarks) was erected in 1880-83.

John Simpson was responsible for the first major alterations and additions to the West 129th Street house, including the construction of the distinctive porch.

In 1882, Simpson filed a permit with die New York City Department of Buildings to add a two-story brick extension to die west side of the building and a two-story wooden bay to the east The additions were to be constructed by Edward Gustaveson, a builder whose business was located at Third Avenue and East 139th Street in the Bronx Drawings submitted with the alteration application show the house as a two-and-one-half-story, peak- roofed structure that was three bays wide.

The drawings show a balcony projecting from the window on the top level and the gable ornamented with a scrolled bargeboard. In plan, the house had a parlor and entrance hall facing the street, a library facing east, a dining room facing west, and a kitchen and a small conservatory to the rear.

The alteration, completed by the end of June 1882, consisted of an extension, ranging in width from seven to twelve feet, to the west, which added space to the hall and dining room, as well as an addition containing a rear entrance and storage rooms for the service facilities.

On the first story, die bay to the east added space to the library.

In April of 1883, Simpson applied for a second alteration, again turning to Edward Gustaveson to complete the work.

This was a proposal to erect a wooden piazza or porch (posts of locust wood were specified) on the rear with a bay above.

The alteration application notes that the rear piazza would be the same as that in front Since no permit exists for the front porch, which extends across the front and east side elevations, and since the porch does not appear on the 1882 drawings, it must be assumed that it was constructed at some point after the 1882 drawings were produced, but before the application for the rear piazza was filed in early 1883.

The front porch with complex woodwork is the most significant architectural aspect of the house. The design reflects the sophistication of nineteenth-century woodworking machinery.

The Moorish- inspired arches, vertical piers, and horizontal railings are articulated by perforated trefoils, quatrefoils, and other features created by scroll saws.

Scroll saws were used in the second half of the nineteenth century to cut the fanciful ornament with perforated designs that were popular on porches, gables, and bargeboards.

These pieces could be cut at local lumber yards and sawmills, as was probably the case with the woodwork on West 129th Street, or could be ordered through catalogs from larger Arms that shipped their products throughout the country.

Although the Simpsons had moved out of the house in 1893, it was not until 1896 that the England family sold the building.

The new owner was the International Congregation of the Franciscan Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart, officially the Missionary Sisters of the Third Order of St. Francis, but commonly known as the Franciscan Sisters of Peekskill.”

This order was founded in 1861 in the Austrian Alps. Four years later, three Franciscan Missionary sisters (from Switzerland, Austria, and Italy) came to America to teach the children of the European immigrants who were settling in New York City.

They established their first parochial school at St. Francis of Assisi Church on West 31st Street and, several years later, opened a headquarters at Mount St. Francis in Peekskill.

In New York City, the order eventually established fifteen elementary schools, two high schools, a college, child care institutes, and business schools.

As the Franciscan Sisters were expanding their mission in the greater New York area, the building at 12 West 129th Street was purchased for use as a convent and reception home for poor children who were to be resettled at the St. Joseph’s Home in Peekskill.

Census records indicate that the house was used primarily as a convent. In 1900, six sisters resided here; in 1903 one priest, four sisters, and eight servants were in residence; in 1920 there were nine sisters; and in 1925, there were five sisters and fifteen children between the ages of two and nine.’

In order to accommodate the new use, the Franciscan Sisters undertook a major alteration in 1896, under the direction of Peekskill architect Asbury Barker.

The alteration entailed the removal of the sloping roof and the construction of a full third story with a flat roof and bracketed cornice.

The addition was covered in clapboards that match those of the lower stories. In fact, an early photograph shows a seamless match between the clapboards of the lower floors and those of the addition, suggesting that the entire building may have been covered with new clapboards in 1896.

The two-story brick bay that had been added to the house in 1882 was extended an additional story; this addition was also sided with clapboards.

Also at this time, a handsome wrought-iron fire escape was added to die east elevation. The high fence that runs along the front of the property may also date from this period.

At the same time that the house was enlarged, Barker also designed a small square summer house for the garden to the east of the die building.

At some time in the twentieth century, perhaps in the 1920s, the house underwent its final planned alteration when the Franciscan Sisters had the entire exterior stuccoed and the comers marked by quoins.

This new facade covering gave the house the air of an Italian Renaissance villa.

Building Description

The 12 West 129th Street House is a rectilinear, three-story structure that is clad almost entirely in stucco (the two-story bay projecting from the west side of the house retains its brick siding). A one-bay wide rectangular bay extends from the east elevation and a single-bay wide extension projects to the west. The comers of the main building and the wings are all marked by quoins.

The main mass of the front elevation is three bays wide and is capped by a wooden cornice supported by brackets and dentils. The main entrance is approached through a porch and is reached via a flight of concrete steps; it is located in the westernmost bay of the front facade.

To the left of the entrance are a pair of nearly floor-length windows. All of the windows on this elevation have drip lintels with roughly-textured imposts.

The windows on this facade, as well as those elsewhere on the building, originally had one-over-one wooden sash.

On the east elevation, the main pavilion is articulated by two windows on the first story, a single window on the second story, and two windows on the third story; each of these has the drip lintels and imposts seen on the front elevation. The projecting pavilion, located near the center of the east elevation, has a single window on its front elevation.

On the side, elevation is a two-story, three-sided, angled bay with a wooden bracketed cornice at each story. This bay dates Rom 1882. Above the bay are three rectangular windows, also with drip lintels.

A wrought-iron fire escape with twisted bars forming “x'”s runs in Ront of the two southernmost windows and extends in a stair down to the ground. To the rear of this pavilion are additional windows (two on the first story and one each on the second and third stories); these windows lack the drip lintels seen elsewhere.

To the west is the two-story brick addition of 1882 with its stuccoed third story. On the Ront, this addition is articulated by a single window on each story (that on the top story has a drip lintel).

Facing west on the first story is a single-story angled bay To the rear of this bay is a small wooden pavilion that retains spandrels with perforated trefoils on top of which is a partially extant band of vertical boards that are cut along their bottom edges.

The upper stories are articulated by crisp rectangular windows.

The most significant architectural feature of the house is the wooden porch that extends across the original section of the Ront elevation and along the eastern side elevation.

The porch, covered by a sloping roof with corbel brackets beneath the eaves, is composed of four arches on die Ront elevation and four additional arches on the east side: at its western end, the porch is connected to the building facade by a single arch. As-built, the porch consisted of Moorish-inspired arches separated by narrow pilasters with beaded edges.

Each arch rested on vertical supports ornamented with openwork quatrefoils and trefoils. The arches were perforated by large and small trefoils and had pendants of stylized foliate details.

In the spandrels of each were additional stylized leaves. The porch railings, each about two feet high, were articulated with a grid of quatrefoils and small diamonds.

(At the time of designation, the pilasters, vertical supports, and railings had been removed because of deterioration.)

There was a similar, two-bay wide porch on the rear. Only the sloping roof of this rear porch was extant at the time of designation.

The summer house, located to the east of the main building, is a small square wooden structure with multi-paned windows, a hipped roof, and a square, hipped-roof louvered cupola- capped by a finial. A tall iron fence, probably added by the Franciscan Sisters, perhaps in 1896, runs in Ront of the entire property.

Later History

The Franciscan Sisters expanded their presence in Harlem in 1921 with die construction of a large building on West 128th Street, immediately south of the house.

This four-story, neo-Gothic style structure (not part of this designation), known as the Assisium Institute, was used as a business school for women, a residence for the students, and a convent.

The Sisters retained die West 129th Street house and the adjoining West 128th Street building until 1941 when they were sold to the Nazareth Mission/Peace Center.

It was used by this and other religious organizations until its sale in 1979 to the Christ Temple Church of the Apostolic Faith At the time of designation, the West 129th Street building was vacant and its windows sealed.

The church, which occupies the former Assisium Institute building, has plans to convert the vacant house at 12 West 129th Street into a senior citizen’s residence in Harlem, NY.

Photo credit: 1-3) The Convent of St. Francis In Harlem NY 1932. source by Charles Von Urban. From 1982, NYCLPC Landmark Designation Report.

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact