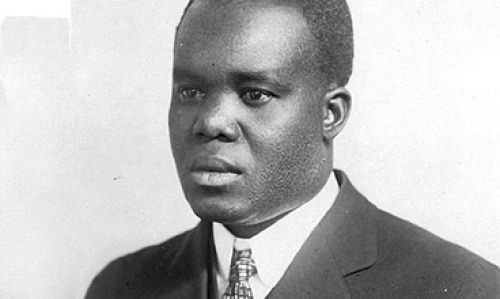

One hundred years ago, on June 12, 1917, Hubert Harrison founded the Liberty League of Negro-Americans at a rally attended by thousands at Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, 52-60 W. 132nd Street in Harlem. It was the first organization of the militant “New Negro Movement.” Several weeks later, on July 4, at a large rally at Metropolitan Baptist Church, 120 W. 138th Street, Harrison founded the movement’s first paper — The Voice: A Newspaper for the New Negro.

The Liberty League’s Bethel rally was called around the slogans “Stop Lynching and Disfranchisement” and “Make the South ‘Safe For Democracy.’” Listed speakers included Harrison, the young activist Chandler Owen, and Dr. Adam Clayton Powell, Sr. (of Abyssinian Baptist Church). Marcus Garvey, a relatively unknown former printer from Jamaica also spoke at the rally in what was his first talk before a major Harlem audience.

The League’s stated purpose was to take steps “to uproot” the twin evils of lynching and disfranchisement and “to petition the government for a redress of grievances.” It aimed to “carry on educational and propaganda work among Negroes” and “exercise political pressure wherever possible” in order to “abate lynching.” Harrison said it offered “the most startling program of any organization of Negroes in the country” as it demanded democracy at home for “Negro-Americans” before they would be expected to enthuse over democracy in Europe.

Two thousand people packed the Bethel church meeting and the audience rose in support during Harrison’s introduction when he demanded “that Congress make lynching a Federal crime.” Resolutions were passed calling the government’s attention to the continued violation of the thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth amendments (regarding slavery and involuntary servitude, citizenship rights, and voting rights); to the existence of mob law from Florida to New York; and to the demand that lynching be made a federal crime. In his talk Harrison also called for retaliatory self-defense whenever Black lives were threatened by mobs.

The Liberty League emphasized “a special sympathy” for “our brethren in Africa” and pledged to “work for the ultimate realization of democracy in Africa — for the right of these darker millions to rule their own ancestral lands — even as the people of Europe — free from the domination of foreign tyrants.” The League also adopted a tricolor flag. Harrison explained, because of the “Negro’s” “dual relationship to our own and other peoples,” we “adopted as our emblem the three colors, black brown and yellow, in perpendicular stripes.” These colors were chosen because the “black, brown and yellow, [were] symbolic of the three colors of the Negro race in America.” They were also, he suggested, symbolic of people of color worldwide.

Garvey, his fellow Jamaican and future Negro World editor W. A. Domingo, and other leading activists, including a number of important future leaders of the Garvey movement, joined Harrison’s Liberty League. From the Liberty League and the Voice came many core progressive ideas later utilized by Garvey in both the Universal Negro Improvement Association and the Negro World. Contemporaries readily acknowledged that Harrison’s work laid groundwork for the Garvey movement. Harrison claimed that from the Liberty League “Garvey appropriated every feature that was worthwhile in his movement” and that the secret of Garvey’s success was that he “[held] up to the Negro masses those things which bloom in their hearts” including “race-consciousness” and “racial solidarity” – “things taught first in 1917 by the Voice and The Liberty League.”

The July 4 meeting at which The Voice appeared came in the wake of the vicious white supremacist attacks (Harrison called it a “pogrom”) on the African American community of East St. Louis, Illinois (which is twelve miles from Ferguson, Missouri). Harrison again advised “Negroes” who faced mob violence in the South and elsewhere to “supply themselves with rifles and fight if necessary, to defend their lives and property.” According to the New York Times he received great applause when he declared that “the time had come for the Negroes [to] do what white men who were threatened did, look out for themselves, and kill rather than submit to be killed.” He was quoted as saying: “We intend to fight if we must . . . for the things dearest to us, for our hearths and homes.” In his talk he encouraged “Negroes” everywhere who did not enjoy the protection of the law to arm in self-defense, to hide their arms, and to learn how to use their weapons. He also reportedly called for a collection of money to buy rifles for those who could not obtain them themselves, emphasizing that “Negroes in New York cannot afford to lie down in the face of this” because “East St. Louis touches us too nearly.” According to the Times, Harrison said it was imperative to “demand justice” and to “make our voices heard.” This call for armed self-defense and the desire to have the political voice of the militant “New Negro” heard were important components of Harrison’s militant “New Negro” activism.

The Voice featured Harrison’s outstanding writing and editing and it included important book review and “Poetry for the People” sections. It contributed significantly to the climate leading up to Alain LeRoy Locke’s 1925 publication The New Negro.

Beginning in August 1919 Harrison edited The New Negro: A Monthly Magazine of a Different Sort, which described itself as “A Magazine for the New Negro,” published “in the interest of the New Negro Manhood Movement,” and “intended as an organ of the international consciousness of the darker races — especially of the Negro race.”

In early 1920 Harrison assumed “the joint editorship” of the Negro World and served as principal editor of that globe-sweeping newspaper of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (which was a major component of the “New Negro Movement”).

Then, in August 1920, while serving as editor of the Negro World, Harrison completed Hubert Harrison’s When Africa Awakes: The “Inside Story” of the Stirrings and Strivings of the New Negro in the Western World. Many of Harrison’s most important “New Negro Movement” editorials and reviews from the 1917-1920 period were reprinted in When Africa Awakes. The book, recently republished in expanded form by Diasporic Africa Press, makes clear his pioneering theoretical, educational, and organizational role in the founding and development of the militant “New Negro Movement.”

Those interested in additional information on Hubert Harrison and the founding of the militant “New Negro Movement” are encouraged to read Jeffrey B. Perry, Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883-1918 (Columbia University Press); A Hubert Harrison Reader (Wesleyan University Press); and the new, expanded, Diasporic Africa Press edition of Hubert H. Harrison, When Africa Awakes: The “Inside Story” of the Stirrings and Strivings of the New Negro in the Western World.

Click here to read more content by Jeffrey B. Perry.

Become a Harlem Insider!

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact